Opinion: When Amherst Voted Down the Future: Revisiting Form-Based Zoning

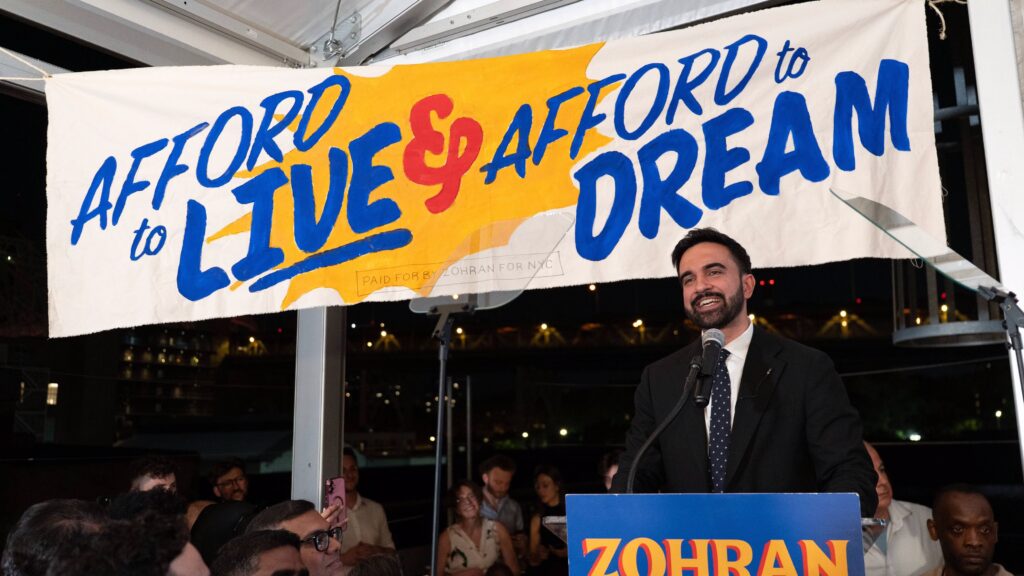

Zoran Mamdani on the campaign trail. Photo: heute.at (CC BY 4.0 International)

Social Inequality Goes Global

In Amherst, around 2010, the Planning Department tried to introduce form-based zoning a forward-thinking way to shape buildings and streetscapes by their physical form rather than their use. The idea was simple: let growth happen, but make sure it looks and feels like Amherst. Keep the college-town buzz without selling out its soul.

Consultants came with charts, renderings, and design codes for North Amherst and Atkins Corner. But when the proposal hit Town Meeting, it failed not because it was wrong, but because no one understood it. Confusion won over comprehension. Amherst kept its old 20th-century zoning: boxes of “residential,” “business,” “limited business.” The form-based proposal became a ghost file buried on some municipal server.

Years later, the consequences stand five stories tall. The “boxy” apartments on North Pleasant — Boltwood Place, Kendrick Place, One East Pleasant — are all technically legal but just not lovable. They’re what happens when you regulate use instead of form.

One retired high school math teacher told me outside the polls who I just met yesterday on November local elections 2025,

“You know what happened? They didn’t understand it. The council members paid to read the reports just shrugged and then they voted it down.” His sigh carries a civic heartbreak.“We hired experts, they made the guidelines, and Town Meeting voted it down because they didn’t understand. Fifteen years later, they’re spending more money to fix what form-based zoning would’ve prevented.”

He’s right. The skyline tells the story. Amherst is now reinventing what it once rejected, piecemeal, under new names: Downtown Design Guidelines, Overlay Districts, character zones. It’s municipal déjà vu with a design budget.

But the missed vote of 2010 didn’t just shape the skyline but shaped the housing crisis. The resistance to form-based zoning froze the town’s evolution. Developers built to the path of least resistance: luxury, vertical, downtown, where land was zoned permissive and profit predictable. The result wasn’t UMass’ fault but a local choice. The town’s inaction fifteen years ago created the very pressures now blamed on students.

And here’s the irony: those same vertical apartments people love to hate, are now the town’s fiscal lifeline. They generate dense, sustainable tax revenue from small footprints — revenue that helps pay for schools, roads, and public services. The fear of “too tall” buildings became the cost of lost foresight.

Compare Amherst’s paralysis to Princeton, where the university decentralized student housing by partnering with local landlords and incentivizing them through LLC structures. Princeton didn’t wait for a market correction created one, balancing the student footprint with town affordability. Amherst could have done the same, but its zoning debate got lost in translation.

The fear of new language whether “form-based zoning” or “structural change” paralyzes the moment. It’s not ignorance so much as nostalgia — what Zohran Mamdani calls the allure of a monoculture, that 1990s comfort zone where everyone watched the same shows, read the same magazines, and believed in the same middle-class dream.

That era — Giuliani’s New York, Graydon Carter’s Vanity Fair, the Balthazar brunch crowd — congratulated itself on normalcy while ignoring the cracks: Abner Louima, Amadou Diallo, and the names that never fit the party narrative.

Mamdani’s generation that toppled Cuomo and speaks in the plural, not the singular and doesn’t want the “immovable feast.” It wants something new, structurally different. The way Amherst could have had it in 2010.

The math teacher outside the polls looked at me as though he’d already seen the sequel.

“People don’t like to admit they don’t understand,” he said. “They just vote no and call it wisdom.”

That’s the quiet tragedy of both Amherst and Washington, not corruption, but comprehension failure. A refusal to learn the new grammar of our time. Amherst’s missed zoning reform and the Democrats’ cautious centrism are twin symptoms of a deeper fear: that admitting confusion is weakness.

But it is the first act of learning and that’s what the younger generation — Mamdani’s voters, the students renting those boxy new apartments, juggling debt, climate anxiety, and the collapse of shared truth — already know. They don’t want another committee report or another safe compromise but a language that finally matches the scale of the crisis and the courage to understand before rejecting.

The change begins not in the next election, but in the next meeting, when someone finally raises their hand and says,

“Wait — explain that again.”

The Other Side: UMass and the Housing Crunch

UMass Amherst is enormous for a town of 40,000. With over 31,000 students and only about 14,600 undergraduate beds on campus, roughly 9,300 of them live off-campus in Amherst and surrounding towns. The university’s land and dorms are mostly tax-exempt, and the town estimates the cost of educating children living in that tax-exempt housing at about $185,000 a year.

Amherst’s housing and tax revenue isn’t just “students vs. residents” but about who foots the bill when so much of the land base is off the tax rolls, and so much housing demand falls on the private market. The off-campus student population squeezes rental availability, drives up prices, and contributes indirectly to the financial pressure on year-round residents. In a system where developers are more incentivized to build luxury apartments for students than affordable housing for families, Amherst’s tax base grows unevenly — vertical student housing generates property tax revenue indirectly through fees, municipal service contributions, and state payments, but the social cost is felt in classrooms, infrastructure, and streets crowded with rentals.

So yes, those boxy five-story North Pleasant apartments are not UMass’s “fault.” They’re the town’s response to 15 years of missed zoning reform and a market skewed toward student dollars. And the question for voters is clear: Do we reward the status quo, or do we demand policies that balance revenue, community, and the right to stay home?

Rizwana Khan is a writer, educator, and human rights advocate in the Town of Amherst.

This is an important piece and Ms Khan is quite right; when form-based zoning was first presented to Town Meeting it was not understood. It took me a long time to realize its significance and its value. It was presented in the language of planners, not residents, and Town Meeting had been accustomed to not understanding Planning Department proposals – and not trusting them.

And Ms Khan is also right that it is time for a fundamental rethink of our ancient Zoning Bylaw in such a way that we don’t have to resort to overlays to circumvent it.

Rizwana, your article brings real insight into Amherst’s zoning history, but I remember firsthand that confusion and objection to form-based zoning also centered around precedent—whether or not each exemption sets a precedent, having more and more five-story private dorms downtown inevitably made those forms what new projects would emulate. Form-based zoning is supposed to restrict such outliers, yet in Amherst, it’s long been easy to secure variances and overcome objections, especially when a developer offers increased property tax revenue.

(For context, the annual taxes from the two current downtown buildings is just $518,000—only about 1/17th of the library project’s massive $9 million budget gap, or 1/86th of our $45,000,000 gap in funding the repair of our failing roads.)

It’s also relevant that (back then) our pro-“develop-anything” planning board chair and department staff strongly championed form-based zoning, which led many residents to wonder if opposing their stance was actually best for the community. We are now wrapping up another two-year planning process, with dedicated Amherst citizens collaborating with consultants like Dodson and Flinker to shape a vision for the town’s future. Despite genuine effort, the process is fractured, with division and uncertainty as participants debate what “the best Amherst” should look like.

Many of us may also recall the moment (on video) when Town Meeting misunderstood that the fifth floor of those big private dorms would be real apartment units—and not just a stepped back rooftop design masking mechanicals.

Finding a solution is not easy, especially when public debate often feels like the Tower of Babel: everyone talking, few finding clarity. In a town “where only the H is silent,” perhaps we need more true silence—more listening. For all Amherst’s reputation as an educated community, we could use a bit more curiosity and humility before closing the debate.

There’s a subtlety missing from this historical account. In 2010, libertarian/neoliberal political forces within the town of Amherst had already sown distrust by trying to get rid of the progressive Town Meeting form of government with two previous “charter” plans, before ultimately being successful on the third try. In 2010, the Town Planner’s word was not trusted by many serving on Town Meeting, so when the proposed Form-Based Zoning came forward, it too was not trusted and rejected. At that time, once a proposed zoning change came before Town Meeting, it was either voted up or down, with no option for “further study.” An option for “further study” was proposed as an improvement to the Town Meeting process, but before that could happen the new charter passed and Town Meeting was abolished. Unfortunately, the leadership of the group trying to save Town Meeting (Not This Charter), decided not to go public about the opposing side representing developers’ interests. To this day, many residents are unaware that the Amherst Forward PAC was formed and continues to serve the interests of developers over those of year-round residents.

I just finished reading Robert M. Fogelson’s 2001 book Downtown: Its Rise and Fall, 1880 – 1950. It’s a study of the problems experienced by large American cities’ central business districts during that period. What struck me were all the planning ideas advanced to solve downtown’s problems and bring about its revival, and how – despite the absolute certainty of proponents – none of these theories translated to a successful reality. The problem with planning is that it begins in the realm of theory and is developed in the mind of the planner, where it is often less constrained by the multiple and unpredictable realities of human social organization.

When Form-Based Code and its proposed implementation in Amherst first came up, I didn’t find it hard to understand. What worried me was that I was unable to find any large-scale practical application of the theory. I searched for examples of built environments that had used FBC, but at most found a block or so, and nothing that would have as widespread a reach as what was proposed for Amherst. In as much as is possible, theory needs to be tested against reality in planning, and it needs to be done analytically and dispassionately, taking into account both its positive and negative aspects, and considering any reasonably foreseeable unintended consequences, so that residents have a reasonable expectation as to how their physical environment will change.

When an article to replace Amherst’s Phased Growth Bylaw was first proposed, I urged the Planning Department to run some theoretical scenarios of its implementation, using projects that had already been proposed or built in town. I was concerned that what had been drafted would not work as planners intended, since my own analysis showed that it could result in more development than expected, thus defeating its purpose. There was resistance to doing this, until right before Town Meeting. And, as I had expected, a theoretical trial run showed that the replacement article would not control development as planners had claimed. It was defeated at Town Meeting. Had planners tested their theory against reality earlier, they could perhaps have made the necessary adjustments to produce an article that would have accomplished what they said it would, and that Town Meeting would have supported.

This discussion has the participants arguing about treating the symptoms of the illness, while the cause of the illness is not mentioned. If the State formula for Payments in Lieu of Taxes (PILOT) on State owned property in municipalities wasn’t rigged to avoid paying for the actual impacts of the activities caused by the occupiers/users/staff/contractors of them, the extreme budget squeeze on permanent residents wouldn’t be as extreme as it is.

Think of the heavy traffic from construction and maintenance contractors, suppliers of food and other materials, waste haulers, landscapers, audiences at athletic and cultural events (revenue for the institution!) on our roads. Think of the air and noise pollution associated with those numbers.

My understanding is that the formula omits assessed valuations of infrastructure including buildings, with only raw land value applicable. Consider the difference! It keeps the majority of the property value off the tax roll, while the costs of the activities of the users are offloaded on the town. Arguing about how to fill that gap without seeking income from the major creators of it is a fools game. It is dividing the permanent residents instead of fostering unanimity in an effort to change the formula. Our representatives at the Statehouse need to be continuously pressured to represent us on this matter.

As a North Amherst resident for 51 years (and downtown on Hills Road before that) and a town meeting member since 1975, I have a very different memory. We understood form-based codes only too well! The models for North Amherst were much too urban, for example, the height of the buildings and the density overpowering the historical Roswell Field Putnam designed story and a half homes along Montague Road. I can’t speak for Atkins Corner residents, but I don’t recall an overwhelming endorsement.

I also made a map for town meeting members showing that only 12% of the dwelling units north of Hobart Lane to the Leverett line were owner occupied. This was slightly after the North Church closed because most its congregants had passed on, their houses becoming student rental houses.

We made the right decision. The article before town meeting would not have impacted downtown development as I recall. It’s easy enough to look at the Town Reports of that year for verification. They are all on line!