Long Division: The Growing Battle over Public School Budgets in Western Mass

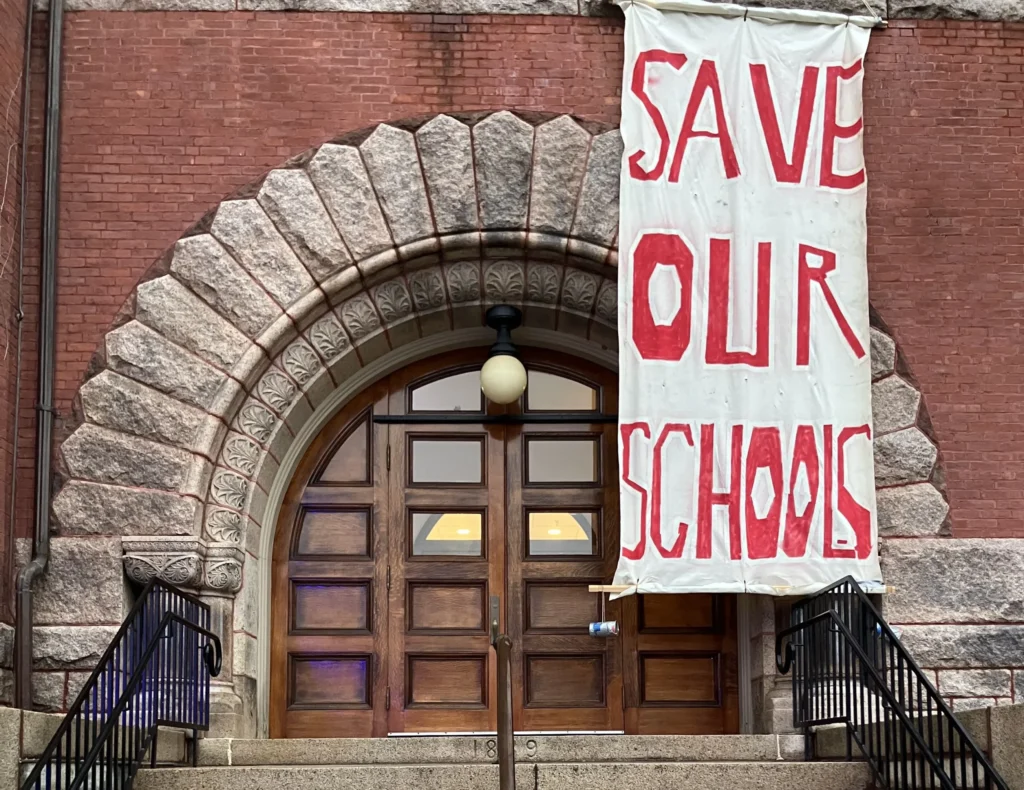

Photo: The Shoestring

by Divina Cordeiro

The following article “Long Division: The Growing Battle over Public School Budgets in Western Mass” by Divina Cordeiro appeared originally in The Shoestring on May 1, 2025. It is reposted here courtesy of MassWire, a web-based news service covering the Commonwealth of Massachusetts and a project of the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism.

Despite attempts to boost the state’s education funding, some cities and towns are facing big budget crunches. Local activists have started to fight for stronger local funding.

In Amherst’s Town Hall, the meeting room is overflowing. Wall to wall, there are parents, students, and community members crowded together, a sea of people filling chairs and standing in the margins of the room. Young and old, long-time locals and new residents alike give testimony — various accounts of how important they feel their schools’ teachers, staff, and extracurricular activities are for students and the community at large.

“We are the experts, we know what’s needed,” said Laura Steinmen, an art teacher at Wildwood Elementary and a facilitator of the school’s LGBTQIA art club. “Fund our schools.”

The crowd was gathered at Amherst’s regular Town Council meeting, protesting beforehand and during the public-comment period with one message: “Save our schools.” State data show that Amherst has a larger population of students with disabilities, and whose first language is not English, than the state’s average. However, a budget proposal in front of the town’s School Committee would have seen special-education and English-language educators cut from the district. The School Committee has since voted to support a budget that keeps services level, but the Town Council can still decide to cut positions.

Amherst community members aren’t the only ones demanding higher school funding amid budget crunches that have resulted in elected officials placing school staff on the chopping block.

Across western Massachusetts, municipalities like Belchertown, South Hadley, and Northampton are having their own struggles working against the knife. Belchertown is voting on a tax increase that, if it fails, could result in over 25 positions being cut in the district after it suffered 17.5 layoffs last year. In South Hadley, as many as 20 cuts are being considered. The Northampton School Committee passed a budget that, if enacted, would claw back 12 of the 20 positions the district cut last year, though they acknowledged that financial difficulties may result in the mayor or City Council ultimately deciding to reject that vote and cut even more positions.

There are several reasons for the financial shortfalls, depending on who you ask. The erosion of federal COVID-relief funds is certainly part of the picture, as is a state funding formula that some communities say has short-changed them. Inflation, transportation, and other cost increases are part of the picture, too. Others, though, have accused their municipal leadership of reactionary thinking and overly conservative budgeting.

But one thing is certain: the slashing will sting.

“A lot of people in the community don’t want some of the cuts. They don’t want cuts to things that they love,” said Fran Frederick, the president of the Belchertown Educators Association and a school adjustment counselor at Belchertown High School. “No one wants cuts to band. Nobody wants cuts to sports. Nobody wants cuts to higher-level classes.”

Some parents say needed services are already missing from their schools. In Northampton, for example, one parent learned that after a meeting about his son’s special-education plan, administrators were caught on a hot mic admitting “we don’t always give kids everything they should get” and seemingly questioning whether the parent was involved with an activist movement to boost local education funding.

Faced with the prospect of paring back already thin budgets, some community members have indeed begun to fight back against what they see as the politics of austerity. In towns across the region, local movements to “support our schools,” or SOS, are popping up. And they’re taking their struggle to local and state politicians alike.

In the Amherst Town Hall meeting late last month, for example, elementary and middle school children spoke up about the importance of extracurriculars to them. In South Hadley, nearly every high school student staged a walkout on March 31 “to send a message to Beacon Hill: fix the school-funding formula,” union officials said. The next week, Amherst and Northampton high school students attended a state Senate Ways and Means Committee hearing in Boston to demand equitable education funding.

“We’re trying to educate people that this isn’t just about the school,” Frederick said. It’s about something bigger, she said: “Save Belchertown and the things that people love about it.”

Nowhere is the burgeoning movement more evident than in Northampton, where the topic of school funding has seemingly permeated every level of the city’s politics, resulting in lengthy, heated meetings of the School Committee and City Council. And school funding will likely be a central issue in upcoming city elections. Every seat on the City Council and School Committee are up for grabs this fall, as is the position of mayor.

Last year, Mayor Gina-Louise Sciarra and a majority of the City Council went forward with a budget that, although it increased education funding, nevertheless resulted in some 20 layoffs. That happened despite the protests of a newly formed “Support Our Schools” coalition and the School Committee’s proposal for a much bigger budget increase that would have avoided staff cuts. Since then, SOS and its allies have loudly advocated for reversing the layoffs and boosting education spending in the city — actions that have put them in conflict with those who see the mayor’s budget, and City Council’s majority vote in favor of it, as sustainable and responsible planning.

“The mayor keeps talking about fiscal stability, but it is not stable to cut staff all the time in a workplace,” Amber Clooney, a member of SOS and resident in Florence, said. “This isn’t a stable city if we’re constantly having staff cuts and layoffs.”

Sciarra did not respond to an interview request for this article. Through a mayoral assistant, she sent a pre-written statement about this year’s school budget.

***

When state lawmakers passed the landmark Student Opportunity Act in 2019, it was billed as a funding fix that would help close gaps in districts with large populations of low-income students.

“Massachusetts made a commitment to public education in the 18th century, and today we are much closer to bringing that commitment into the 21st century to meet the needs of students today,” state Senate President Karen Spilka said at the time.

For many districts, the bill has been a success. But despite an increase of over $1 billion in funding over seven years for the state’s K-12 education system, even some of those districts are now struggling with their budgets as COVID-relief money runs dry, inflation pushes prices up, and districts face increases in costs for budget items like transportation and out-of-district special education tuition. In some cases, they’re spending that money to keep services rather than expand them.

“Even the districts like Pittsfield and Springfield and Holyoke and so forth, those [Student Opportunity Act] increases to cover their operating costs, they’re not actually going to be able to use them for what they’re supposed to be able to use them for, which is meeting the needs of the low income students and meeting the needs of their English learners and so forth, in the ways that the Student Opportunity Act outlines,” Tracy O’Connell Novick, a finance and state education funding expert at the Massachusetts School Committee Association, told New England Public Media last year.

For many rural districts or those with fewer lower-income students, the situation has become dire and has led to staff cuts. Those districts have found themselves receiving the minimum aid from the state, which they say isn’t enough.

“We’re not getting enough funds for everything,” said Max Page, the president of the state’s educators’ union, the Massachusetts Teachers Association. And that was before this year’s wave of education cuts across the state. “Every year, there are educators lost, supports not provided. Students need more support.”

The Massachusetts Teachers Association has led the fight for more education funding in recent years. In 2022, for example, voters in the state approved the MTA-backed Fair Share Amendment ballot question, which raised taxes on income over $1 million dollars and dedicated that funding to schools, colleges and universities, roads, bridges, and other public transportation.

Amid the more recent challenges to education funding, a statewide coalition of unions and school leaders known as United for Our Future has come together advocating for a revamping of Massachusetts’ school funding formula. Although Spilka, the Senate president, has expressed interest in updating the state’s school funding formula, known as Chapter 70, House Speaker Ron Mariano shot down that idea when speaking to reporters at a Greater Boston Chamber of Commerce event in early April, according to the State House News Service.

“No,” he reportedly told reporters at the time. “Too much uncertainty.”

United for Our Future aren’t the only ones mobilizing. Education funding is also a local battle. Municipalities get a substantial portion of their schools’ budgets from property taxes, and some organizers have begun to dig in at the city and town level, too.

***

Cathy McNally is a long-time resident of Northampton. Her children are adults, but her passion for education was reinvigorated by the city’s budget crisis last year. She was “moved by the high school kids” who spoke out about their concerns that their theatre teacher was going to get laid off due to budget cuts.

So, in April 2024, she did what so many do nowadays when frustrated with local politics: she founded a Facebook group.

The group was christened with its namesake last June: Support Our Schools. McNally was surprised that people began joining the Facebook group, and recalled getting excited as the group’s numbers grew. Now, the page has over 600 members, and this past summer Northampton’s SOS group held its first full organizational meeting, where they formed committees focused on topics like research and outreach.

The group also formed its own political action committee, aiming to unseat candidates for office this fall who don’t support substantially increasing education funding.

The Shoestring relies on readers’ support to make independent news for Western Massachusetts possible. You can support this kind of labor-intensive reporting by visiting our DONATE PAGE.

Amber Clooney, an SOS member and parent, said she joined the group after seeing a letter to the editor in the Daily Hampshire Gazette suggesting that it would be fiscally prudent to limit the city’s school budget.

Both Clooney and McNally are frustrated by Sciarra and other city officials’ responses to community concern over the school budget — feelings shared by those in their group. Sciarra has consistently said that she’s looking out for the overall fiscal stability of the city and its schools. When advocates suggest that she use the city’s reserve accounts to stave off staff cuts, she has said that putting any non-recurring revenue toward recurring expenses in the schools, like salaries, will lead to a budget shortfall in subsequent years. And with more financial turmoil on the horizon under the Trump administration, education funding could be in even more jeopardy.

On April 11, the School Committee passed the most ambitious of three budget proposals Superintendent Portia Bonner had put in front of the body. By an 8-2 vote, committee members supported a 12.5% increase in school spending, which would allow the district to hire more than a dozen additional positions. Bonner had also proposed a 7% increase, which would have allowed for level services.

But on Monday, Sciarra announced that she would be devoting nearly $43.9 million to the school district — an increase of just under 6%. She said it was the fourth consecutive fiscal year that the city has increased funding for Northampton Public Schools by at least 5%, which she said has not happened in the previous 50 years.

“The 5.88% increase reflects both how deeply we value our schools and how carefully we must balance the rest of the city’s obligations,” Sciarra said in a five-page statement outlining her decision.

According to Sciarra, the schools’ “actual net school spending” — direct spending and indirect spending, like employee benefits — was 144% of the state-determined minimum this fiscal year. That was the highest for Northampton Public Schools since 1993, she said, and more than most nearby districts.

“Northampton’s state aid only accounts for 16% of our actual net school spending,” she added. “This has fallen since the 1993 Education Reform Act, when it was 33%.”

Sciarra said in the statement that she would also be transferring $1 million from the city’s Fiscal Stability Stabilization Fund to go towards the city’s schools. It’s the third year in a row she has used money from that fund for the schools, she said, totaling $4.2 million.

Yesterday, the Gazette reported that Bonner expects to make over $650,000 in reductions to services under Sciarra’s budget that would avoid layoffs but still result in the loss of several educators’ jobs through retirement or attrition, including a fifth grade teaching position and a middle-school technology teacher.

The cuts would also impact some services in the district, the Gazette reported. For homeless and foster care youth, for example, $70,000 in transportation funding would be cut as the district looks for other modes of funding from the state. Bonner told the Gazette that the transportation will not be completely dissolved. Additionally, across schools like Bridge Street and Northampton High, professional development stipends and dual enrollment at community college would be whittled down.

Sciarra’s critics have suggested that she needs to be using far more of the city’s reserves to plug those kinds of holes in the school budget. They say that despite steep staffing cuts in recent years, Sciarra didn’t restore any of those positions with an $11.6 million free cash surplus Northampton had this year. They’ve said she’s prioritized saving money over using it to fund education and other city services.

For Clooney, “the money isn’t actually any good” if it’s in a reserve account.

“If your house is on fire, you don’t want a pile of money, you want firefighters. If you’re constantly cutting the fire department and you don’t have anyone to respond to the emergency, then the pile of money does nothing. It’s the same with the schools,” Clooney said. “The best way to respond to the national situation is to have a stable and trained and long-term workforce of great teachers, which we have and we’re going to lose if we don’t fund the schools appropriately.”

Activists in other western Massachusetts municipalities have followed suit, calling for a local response to realign budget priorities around their towns’ schools. At the University of Massachusetts Amherst, a hearing of the state Legislature’s Joint Committee on Ways and Means was held in late March, which drew the attendance of middle and high school students, families, and community members from districts across the region. According to the Gazette, the lack of financing for rural public schools and the burden it causes was a “constant theme.”

In early March, Belchertown community members flooded the town’s Select Board meeting to discuss another method of funding schools: a proposition 2.5 tax override, which is how a municipality increases property taxes for residents beyond the 2.5% levy limit allowed yearly under state law.

“No one’s saying that this is a blank check. I think that’s the perception by some people,” said Frederick, the Belchertown educators’ union leader. “We’re looking to keep the lights on, right? We’re looking to keep the school running.”

While Frederick said she doesn’t think that proposition 2.5 is the “total answer” to the budget crisis, she says it’s “part of the solution.”

In Northampton, city officials and advocates alike have discussed the possibility of raising taxes, too — a contentious proposition for some community members. For example, Diana Shwartz, a parent in the city, said in an interview that she has voted for every single override in Northampton in years past, but that she will not vote for another one until the city commits to supporting the schools.

Sciarra has said that the budget she’s proposing will mean that a $3 million override won’t be needed until fiscal year 2027.

Defensive action is also being taken at the state level.

Earlier this month, U.S. Sen. Elizabeth Warren launched her own “Save Our Schools” campaign to “fight back against the attack on public schools” that the Trump administration started. According to a Facebook clip, Warren’s plans for this campaign include launching an investigation into the actions of Trump and his ally Elon Musk and collaborating with students, teachers, and lawmakers in Congress. Warren has called for an investigation into the material impacts of the Trump administration’s cuts to education.

But not everyone is happy about some of the activism happening on the local level. McNally, for instance, said “there’s been an enormous backlash at SOS for being sort of divisive or criticizing the mayor.”

Northampton’s School Committee will witness the turnover of seven of its nine members who took office two years ago and several city councilors have also said they’re not running for re-election. In a recent op-ed in the Daily Hampshire Gazette, city resident Josh Silver suggested that one of the reasons for that turnover is that “hostility and acrimony dominate marathon-length City Council and School Committee meetings.” He suggested shortening public-comment periods in those meetings, enforcing rules against ad hominem exchanges, and keeping meetings more focused on agenda items.

“Supercharged by toxic social media posts, ugly personal attacks have become more common than fact-based, collaborative debate in Northampton,” he wrote. “It eerily mirrors our broken national discourse, and it must change. Recently, I’ve asked friends and acquaintances to run for local office. The overwhelming response: ‘Why would I sign up for endless, acrimonious meetings that are routinely commandeered by a handful of toxic, filibustering mudslingers?’”

But McNally said it’s important to criticize local policies and people in leadership, especially those who she said are “hollowing out democracy” on the local level.

“We’re so mad at Trump and the Department of Education for being dismantled. We think that’s horrible,” McNally said. “But what are we doing here? Aren’t we doing the same thing? Only we’re sad about it. It’s good to fight Trump, but you know, you got to deal with what’s in your backyard.”

***

Earlier this month, the Trump administration announced that it had cut over $100 million in federal funding for K-12 education in Massachusetts, more than $47 million of which was for Springfield alone. Holyoke and West Springfield were also impacted by the cut to the federal Education Stabilization Fund, which state leaders said in a press release “was intended to support a multitude of statewide efforts to address pandemic-related learning loss, with a focus on literacy, math and science – areas where learning was particularly disrupted during the pandemic.”

This termination of funding comes after the Trump administration’s executive order to dismantle the Department of Education. And Trump has threatened to withhold federal funding from schools that promote diversity, equity, and inclusion, setting up a showdown with states like Massachusetts. The state’s education commissioner rejected Trump’s demand earlier this month in a letter to the Department of Education.

“Massachusetts will continue to promote diversity in our schools because we know it improves outcomes for all of our kids, and we have more work to do,” Interim Commissioner Patrick Tutwiler wrote.

But the state’s funding cuts are chronic, according to some experts, and have already had far-reaching impacts.

According to a report released by the Economic Policy Institute, systematically cutting funding for public education negatively impacts all students, but particularly students of color. It added that issues caused by funding cuts are “magnified during and after recessions” and that an increase in spending on education can support the recovery of the economy.

Another report from the Education Law Center found that from 2008 to 2018, students nationwide “lost nearly $600 billion from the states’ disinvestment in their public schools.” Using an index that calculates K-12 education revenue as a percentage of a state’s economic activity or GDP, the researchers found that in that time period, Massachusetts divested 12% from its public education system — more than 29 other states.

For Massachusetts-based education writer Jennifer Berkshire, the co-author of the book “The Education Wars: A Citizen’s Guide and Defense Manual,” the attack on public schools is an attack on democracy.

Berkshire views public schools as a space for kids of all backgrounds to come together, to prepare “young people for citizenship.” She said that even though there are critiques of the school system, people understood in the past that public education gave children the experience needed to interact in a multi-racial democracy. With the commodification and privatization of education, she thinks people are losing sight of that.

“The less people understand something like ‘public education is a public good,’ the easier it is for them to say, ‘Why should I have to pay for it? Why should I have to pay for your kid?’” Berkshire said. “Once you lose sight of the idea that it’s a public good, then not only can you justify spending less on it, but it’s also much easier to justify privatizing it.”

As municipalities cut back on music, art, and other programs, parents are faced with the difficult decision of where to send their children to school — a sentiment repeated during Amherst’s Town Council meeting. During that meeting, some caregivers shared that they were considering “choicing out” of the district, using the state’s school choice policy to send their children to other schooling options, like charter and magnet schools, using public money.

Berkshire said that when families “choice out” of their communities, schools in the district then have a disproportionate amount of children who have special needs, who speak English as a second language and are in the process of learning it, and children who are low-income. She said that by cutting education funding, districts are “essentially incentivizing parents to move out of particular communities and find new ones.”

“And then it means that there are fewer resources available for the kids who are left behind,” she said. “And so you see schools closing, teachers being laid off. And I think what’s challenging for especially today’s parents, they feel so much pressure to give their kids the best possible preparation to thrive in an uncertain world, so they’re acting rationally.”

***

“We’ll go to war.”

That’s the last phrase someone might expect to hear from a school official, much less someone who had just finished talking with a parent about their child’s special education services.

But that’s exactly what Guarav Jashnani, the father of a child in the Northampton school district, found on a transcript from a January meeting with administrators about his kid’s individualized education plan, or IEP. A hot mic had seemingly caught an unnamed participant’s feelings on Jashnani’s advocacy for his child’s needs, referring to him as a “pain in the ass.”

And that’s not all that was caught on the recorder.

“The reality of the situation is that we don’t always… I mean, we should, but we don’t always give kids everything they should get on their IP,” the transcript says, likely referring to an IEP. “In some way, and this is not a good thing, but in some ways I do think it’s kind of understood, that sometimes there isn’t coverage or sometimes there isn’t staffing or whatever. But then there are some people who, like this, come from a different community.”

In addition to admitting that Northampton schools don’t provide all students with their legally mandated special education service, the speakers on the transcript also seemed to take aim at Jashnani’s activism. They questioned whether he was a member of “Save Our Schools” — possibly a reference to “Support Our Schools.”

“The implications are really scary for people like me who have children receiving special education services,” Jashnani told The Shoestring. “If we have the wrong political opinions, then our kids might not get what they need.”

Northampton Public Schools Superintendent Portia Bonner did not respond to interview requests seeking to talk about the complaints of Jashnani and other parents.

In response to Jashnani’s formal complaint to the state about his child’s allegedly lacking services, the district has denied wrongdoing, according to reporting from The Boston Globe, which first broke the story.

“Please know that the district is investigating this matter fully in consultation with our legal counsel,” Bonner told The Globe in response to the leaked transcript. “We will apprise the community when we have further information.”

Jashnani revealed the transcript at a School Committee meeting in March. The previous month, he had spoken up — together with other families, students, and school staff — about the impacts that they said the previous year’s layoffs have had on education services. After speaking with other parents and neighbors, he said at that meeting that his child’s experience with lacking services was common in the district.

“Every day, this district is failing to provide legally mandated services to dozens, if not hundreds, of students,” he said. “These are lawsuits waiting to happen. Again, it’s a fiscal issue. Why? Because the city has cut staff to the bone.”

Other parents say budget cuts have impacted their children even prior to last year’s layoffs.

Andrea Bertini and Diana Shwartz say they have been “fighting with” the Northampton school district to comply with their son’s special education accommodations for seven years. They’ve said they’ve filed complaint after complaint, that their child has switched schools several times — once for bullying — and that allegedly the district has yet to provide the consistent and individualized support to meet their child’s needs.

“It’s just constant. It never ends. It’s exhausting,” Shwartz said. “And there’s a lot of rage for sure, because it’s your kid, right? You just want what’s best for them.”

Shwartz alleged that “Northampton doesn’t even try to follow the law.” She said that Northampton frequently misses deadlines for submission of documents, that she and Bertini never receive the legally required drafts before their IEP meetings, or documentation of the district’s refusal to their requests. The delays and failure to comply with the timelines of the procedures means that their son doesn’t get the help he needs, they said.

“In the meantime, years go by,” Shwartz said. “We’ve been fighting to try to get our son an appropriate reading intervention all year. He’s lost three quarters. He’s going to lose two thirds of the year, and he’s not going to get any help.”

“You feel like you’re failing a lot of times,” she added. “You feel like, you know, you’re failing your kids. You’re not doing enough.”

In both parents’ cases, they said they learned about the alleged non-compliance with their children’s IEPs by accident. It was their children, not the district themselves, that reported not having their mandated in-school supports, they said. In Bertini and Shwartz’s case, they said their child revealed that he hadn’t seen a paraprofessional for support in the classroom for the first thirty days of the school year.

Jashnani said he learned from his child that there was frequently no paraeducator present, contrary to the child’s IEP. So he asked the district about it. Jashnani said that the district told him that there was no disruption to his child’s daily paraeducator support. But then teachers confirmed a paraeducator was only present one third of the required time, he said. That led him to file a complaint with the state, which he said sided with him. .

“I see there’s a chasm between those things,” he said. “This is a city that says, ‘We’re progressive. We believe in racial equity. We believe in creating a city that welcomes everyone.’ And what’s happening in practice is the city has not. They’re not just not giving people what they need. They’ve been actively taking away what they know children of color, poor children, migrant children, children with disabilities — they’ve been taking away what these kids need.”

Jashnani said that there’s a direct throughline between the city’s current battles over school funding and the situations that he and other parents are facing.

“Now I think my child is getting the services, but I don’t know because [the district was] lying to me before,” Jashnani said. “I’m worried retaliation will take the form of their direct interactions with my child.”

Jashnani alleged that he hasn’t received information about any investigation conducted over the remarks made in the transcript.

***

SOS continues to organize and mobilize over the budget. The Facebook group is updated nearly every day with either a post about a rally, a city meeting, or intersecting, informative, or otherwise inspirational posts.

Invest in Belchertown: Vote Yes, is another Facebook group that has arisen from a budget crisis and a lack of funding for the town’s schools.

With over 800 members, organizers in Belchertown are advocating for a $2.89 million tax override, with volunteers door-knocking to inform their neighbors about the effort. One organizer even brought their child along for canvassing. Earlier this month, the group posted a Q&A video in which Jake Hulseberg, an assistant principal at Wilbraham Middle School who has two children who attend Belchertown Public Schools, walked the audience through what an override would cost individual taxpayers. The video is the eighth in a series that discusses the potential impacts of cuts and why the organization is endorsing an override.

“It’s for the same services, the same programs, the same schools we had last year,” Hulseberg said in the video. “It doesn’t really make anything better, it stops things from getting worse. A lot worse.”

Invest in Belchertown: Vote Yes also created a website where people can find a variety of monetary impacts on their household if the override were to be approved. They also advocated for the town’s Select Board and town moderator to create an informational guide on town meetings, so “people can learn what it’s like and what it’s all about.” This is all occurring just a few weeks before in-person voting on the proposition 2.5 override will occur on May 19.

The struggle proliferates through every step of the political pyramid.

On the state level, Attorney General Andrea Campbell was one of 21 attorneys general who sued the Trump administration over “unlawful efforts to dismantle” the Department of Education. In a press statement, Campbell said that the education department enforces anti-discrimination laws and supports programs for children from low-income backgrounds and those with disabilities.

“The Trump Administration is making it crystal clear that it does not prioritize our students, teachers or families,” Campbell said. “Neither President Trump nor his Secretary have the power to demolish a congressionally-created department, and as Attorney General but most importantly as a mom, I will continue to hold this Administration accountable for illegal actions that harm our residents and economy.”

***

Nora De La Cour is a former teacher and counselor, having taught in Springfield and counseled in Westfield. Now, she lives in Easthampton and has frequently written about education for news outlets including The Nation and Jacobin, including the local battles over education funding. For De La Cour, the attacks on public education have far-reaching impacts.

“Part of what all those attacks do is they kill our imagination and they make it feel like there is no purpose in dreaming and there are no solutions,” De La Cour said.

She said that she’s observed how all over the western part of the state, the school budget has become a major avenue for communities to engage in political struggle — particularly people who aren’t parents or might’ve not become politically activated otherwise.

For De La Cour, it’s “the gateway drug for other kinds of political activism.”

“The assaults on public schools mobilize us all to fight for justice in every aspect of our lives … and just keep making the case over and over again that we need funds for public schools,” she said. “Not just so that kids can test higher, but so that they can experience joy in their childhoods and go on to be deep and critical and multifaceted people.”

But for De La Cour, she’s observed how school committees center their work around how to live with budgetary constraints and moving money around. Instead, she said, they could focus on the different possibilities of what education could be — spaces where children could get what they need to “be joyful and vibrant and thoughtful” rather than feel like “automatons” that focus solely on the employability of students. The current model, she said, allows those in power to elude accountability for manufacturing inequities. Instead, it justifies those systemic injustices.

Schools don’t have to just be sites where students learn; they can be a space “beyond training kids for the job market,” she said.

“I think it’s so important to keep dreaming,” she said.

Update: This article has been updated to correct the spelling of Cathy McNally‘s name.