Views on Views: Walking The Edges

Secen from a UMass foraging workshop, offered by the UMass Permaculture Program in October 2025. Photo: Hetty Startup

This is the first of a series of 10 articles on landscape design in Amherst.

I’m beginning a series of articles focusing on landscape design in Amherst. This requires more than a little chutzpah because I don’t have a professional background in the field. But my graduate work took shape in a department of architecture and landscape architecture, so I am going to forge ahead, claiming a tiny bit of formal knowledge, supplemented with things I have learned along the way.

Indy readers already know and appreciate that we live in an interesting, distinctive, and beautiful part of the state. We owe this miraculous landscape to glacial Lake Hitchcock and the lives of those who have come before us. Especially, we owe it to those who have been negatively impacted by the way the land has been appropriated over the last several centuries by colonial settlers who changed the ways the land had been previously understood.

When I walk or drive around Amherst and the Valley, I try to envision initiatives such as rematriation (Indigenous women-focused work to restore sacred relationships between Indigenous people and their ancestral land), how this might take place, and also what would look the same or different; I try to imagine the landscape without four centuries of intense Western-style extraction of the land’s resources and visual qualities. This entails blocking out all the industrial mills that remain from the mid-1800s, often made of brick or stone, and the many that have now often been adaptively re-used as offices, housing or recreation. The past is the past and we move on, but I still try this imaginative exercise and want to remember.

I also appreciate many current treasures and want to preserve them into the future: the charm of the Olmsted-designed Wildwood Cemetery, the swathes of daffodils at the Orchard Arboretum at Applewood in South Amherst, the many sites of natural beauty protected by organizations like the Kestrel Land Trust, the groomed campus grounds at UMass, Mount Holyoke, and Smith College. I relish visits to places like the Kinsey-Pope Garden on High Street in Amherst, or walks with family and friends through the fields of the UMass Student Farm.

I keep an eye out for viewsheds, a funny word that specifically means what can be seen geographically from a particular vantage point. The idea of a viewshed is inscribed into our vocabulary by Amherst’s street names like Prospect or Pine Ridge or more generically, a road named Maple Street. The natural element suggests a specific space, even a sense of place. The charm behind a viewshed or a specific landscape design was identified by the American writer and landscape designer, Frederick Law Olmsted. As a result of his own experience and wide reading, he concluded that the most powerful effect of scenery was one that worked by an unconscious process, almost as if by a [magic] charm.

Many times, tiny insights into the landscape around us suggests something peripheral and pretty—the delicate embroideries of portulaca, for example, on the edges of herbaceous borders and town sidewalks. Sometimes the experience is larger in scale. think, for example, of the siting of houses on places called The Heights (actually, I am not sure Amherst has a Heights neighborhood) and where that design approach may have originated? Higher ground has been venerated since ancient times. And as we encounter the topography of our surroundings, we might notice a stand of specimen trees, a small home-sized apple orchard, or a cemetery, all possible examples of historic landscaped sites of significance or importance.

Our landscapes are mostly managed and even manicured, although wilder lands and views are possible to see. Rewilding happens and is advocated by climate activists as a way of preserving natural landscapes. But what dominates landscape design currently is what we find in Amherst Center, for example. Think how ordered and bordered our North Common is, compared to the way it was in the very early 1800s.

Similarly, Groff Park, well thought-out in terms of our current needs for open, accessible, green space and recreational facilities, has evolved from the basic swimming hole that once was enough to entertain and attract townspeople in earlier centuries. This town park is a public amenity located by the Fort River and the Emily Dickinson trail that also skirts meadows and wetlands.

UMass Permaculture

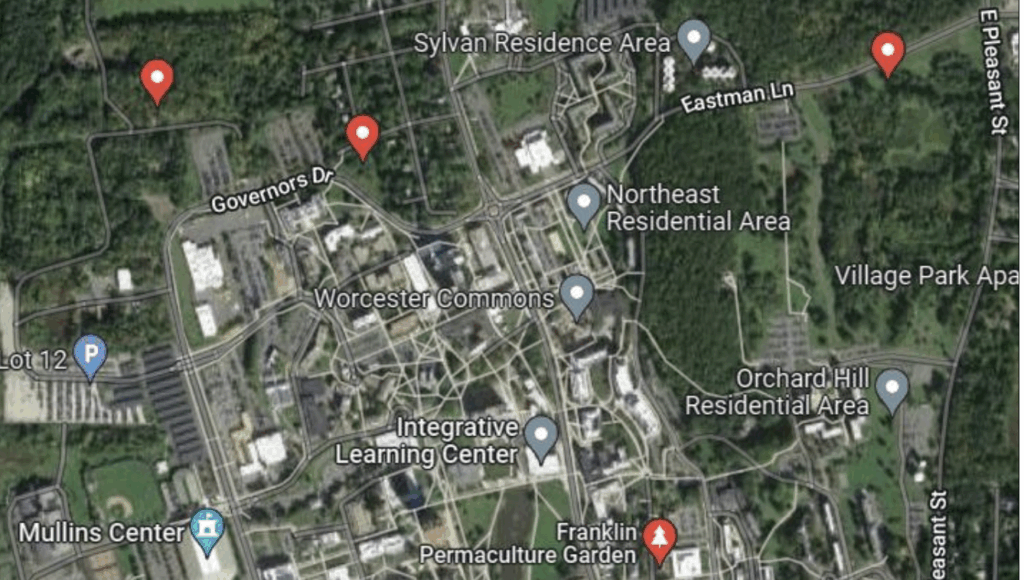

I want to finish this first article by concentrating on a couple of landscapes on the edge of the UMass campus. They are both small gardens worked as part of the university’s Permaculture Program and depend on local footfall, perhaps, to be truly appreciated.

Last week, walking with a group of people by the new Computer Science Laboratories at UMass, we moved quickly from a busy road and heavily landscaped settings to those that at first seemed much wilder. There is a small permaculture garden here although it is not the first one that was created, which is located near the Franklin Dining Commons. The experience of being in this kind of landscape was mediated because I was part of a Foraging Workshop offered to the UMass community by the Permaculture Program. Exploration, smiles, a little instruction, a sharing of resources, and some time in nature–and in community–were all a part of the afternoon.

We first got to know a little about the other people joining the walk and that meant we might have a walking buddy as we set off into the woods. My partner for the exercise lives with an axolotl. But we also first listened to Dan Bensonoff who had tips for our walk and experienced observations from many years working with foraged plants and fruits.

We helped a little with a wild hickory loco-harvest while learning about some of the berries and fungi (the very safe ones) we might see around us. We actually saw virtually no mushrooms ,no doubt due to the lack of rain this summer. We headed off single file, noticing wild mustard greens and crabapple trees along the way.

One of the pleasures of the walk on that beautiful early fall afternoon was its local focus, and the fact that I could chat along the route with students and staff from UMass as well as people from the community. We were walking very close to an established neighborhood by UMass, the Fairview neighborhood, and this meant that some of its residents had joined the walk as well. When we think of a special place, we might recall the writings of someone like Jane Jacobs, who understood that the character of a neighborhood is partly about the way it looks and feels (as designed spaces, buildings and infrastructure) and partly about the people who inhabit it and make it feel special in other ways.

The campus’ other permaculture garden, a landscaped area on the southern edge of the UMass campus, is a garden created by the Class of 2012. The area had previously been used as a construction staging area and was very neglected.

The class was able “to demonstrate the regenerative capacity of permaculture landscaping. In one year, we transformed this neglected site in terrible condition into an ecological haven with rich, fertile soil and high species biodiversity.”

I tried counting all the different flowers, plants, and trees, looking up high or down low, and I smiled at the chestnut trees, the abundant chives, and a patch of what looked like squash in a tiny overall area that is about a tenth of an acre.

While writing this article, tt was impossible not to ponder the death this past week of Jane Goodall, who wrote about her time with animals and the natural world in the following way:

Jane Goodall

While writing this article, tt was impossible not to ponder the death this past week of Jane Goodall, who wrote about her time with animals and the natural world in the following way:

“…Lost in awe at the beauty around me, I must have slipped into a state of heightened awareness. It is hard impossible really–to put into words the moment of truth that suddenly came upon me…Even the mystics are unable to describe their brief flashes of spiritual ecstasy. It seemed to me, as I struggled afterward to recall the experience, the self was utterly absent: I [and the chimpanzees], the earth and trees and air, seemed to merge, to become one with the spirit power of life itself. The air was filled with a feathered symphony, the evensong of birds. I heard new frequencies in their music and also in singing insects’ voices–notes so high and sweet, I was amazed. Never had I been so intensely aware of the shape, the color of the individual leaves, the varied patterns of the veins that made each one unique. Scents were clear…easily identifiable: fermenting, overripe fruit; waterlogged earth; cold, wet bark; the damp odor of chimpanzee hair, and yes, my own too. And the aromatic scent of young, crushed leaves was almost overpowering.” ~

Foraging Resources

Some resources from UMass’s permaculture program that Dan Bensonoff shared with the group afterwards included: cookbooks like The Forager Chef’s Book of Flora by Alan Bergo, guide books such as Samuel Thayer’s Forager’s Harvest and podcasts like “Eat the Weeds.” At the time of the pandemic I found my way to the YouTube site of the Black Forager and she is informative and inspiring and joyful. There is also a site that focuses on food inequality and food justice called Help Yourself Edibles.

“Walking the edges” is a very contrary way into this series but it is the closest in the series I will probably come to an idea of a wilder nature. And one where the writings of the botanist and Potawatomi author Robin Wall Kimmerer are a guide and a friend, like Dan was to us all on the foraging walk. I hope this series might make you look a little differently at your back yard, if you have one, or your porch or favorite public park (perhaps it is Kendrick Park or Amythest Brook?). As there are nine more installments, I will also be looking at the town’s open spaces, its fountains, its trees and the amazing work of the Shade Tree Committee and the role of the Conservation Commission in helping us to preserve special places. There are several designers who, in the course of history, have contributed hugely to thinking about landscape in ways that are like architecture…..such as places of “discovery and arrival, ” a term of art used by the founder of the Conway School of Landscape Design, Walt Cudnohovsky.

Photo: Hetty Startup

In the meantime, as of this writing, I hope you have picked your dahlias because round here we have a hard frost tonight, and this flower beloved by the Aztecs will need to come inside to survive. I don’t plan to cover specific gardens of residents of Amherst but do pipe up if you would like to be featured.

I can tell that this will be a magnificent series, and it is off to a wonderful start. It encourages us to return to Thoreau, Whitman, Emerson and even Abraham Lincoln, who all had important insights into the centrality of the “edge”. And the centrality to thinking of “envisioning” and “imagining.” Thank you.

Thanks, Michael. It was an article of yours [https://www.amherstindy.org/2019/08/30/landscape-streetscape-and-skyscape-the-aesthetics-of-planning-in-amherst/] that got me thinking about doing something like this. In our Book and Plow town, lovers of our town might like this link to take them to signs of autumn walks by water, in woodland and farmland. https://www.kestreltrust.org/places/amethyst-brook-conservation-area/

I find your articles about Amherst architecture and landscape fascinating. However, I would like to call attention to the caption on your last photo: “cattails or what is considered an aquatic nuisance weed (Phragmites australis). . .” I’m not sure if you meant to imply cattails are the same thing as Phragmites, but they are not the same thing. Cattails are a native plant and provide food and other uses to both people and wildlife according to Robin Wall Kimmerer in her book, “Braiding Sweetgrass.” Its presence is a sign of the health of a wetlands. On the other hand, Phragmites is an invasive plant that provides little in the way of nutrients.

What I miss most from the 19c. post cards of Amherst are the elms arching over the downtown and North Amherst commons in particular. Not only are the elms gone but new species being planted downtown and on University Drive have a more perpendicular upright growth pattern and older street trees are sheared to oblivion to protect electric wires underneath. I also note that in summer, particularly, the temperature in north Amherst can be five degrees cooler than downtown—in part from the exposed unshaded black pavement.

Dear Elissa Thanks so much for the clarification on something that could have been very ‘off’ and for reading my articles. Warm best, Hetty