Almanac: Vernal Chorus

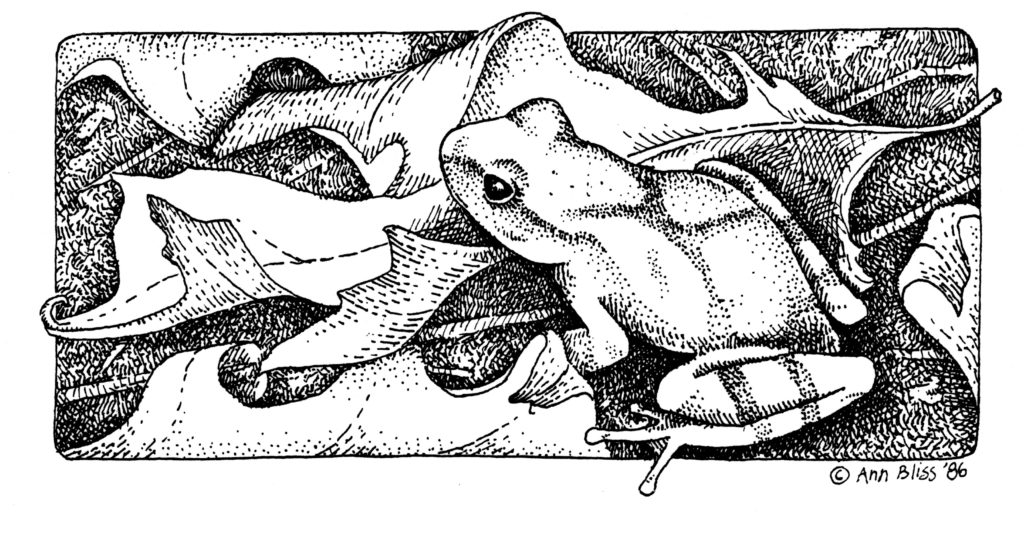

Illustration: Ann Bliss

By the time I turned off the light in the sugar house in North Amherst yesterday after a long evening of boiling sap the air was still mild from the day’s unseasonable warmth. The moon was high and encircled with a halo of pale light, a portent of coming rain. Then, for the first time this season, I heard the rhythmic songs of spring peepers rising from the marshy area across the road.

Peepers are tiny brown “chorus frogs” marked with a black “X” on their backs. (Their scientific name, Pseudacris crucifer, alludes to this cross-like marking.) To hear the volume of sound these animals produce, you’d think locating them would be easy. Not so. They are amazingly elusive. First, they’re only about an inch long and colored to blend with their surroundings. Second, they usually sing at dusk and into the evening. Third, they are extremely sensitive to noise and vibration, and they shut up as soon as you get near them. I’ve never seen one in all my years enjoying their music.

The males do the singing, establishing a small territory and trying to attract females, who choose mates based on the speed and volume of the songs. Older, larger males tend to have faster and louder calls, which are preferred by the females. Size and age aren’t all that count, however. Sneakiness can be effective, too. So-called ‘satellite males’ do not sing. Instead, they position themselves near loud males and attempt to physically intercept females drawn to the calls. A calling male who detects another male in his territory will change from the classic “peep” call to a warning “trill” sound. If that doesn’t deter the intruding male, amphibious fisticuffs may ensue.

Peepers sing by passing air back and forth over vocal cords located between their lungs and the stretchable skin flap under their chins. Peepers differ from classic water-loving frogs in that they have sticky disks on their toes for climbing vegetation. This is why they were once classified as tree frogs, in the genus Hyla. Peepers have most of the normal frog equipment, however, such as a tongue attached at the front of their mouths (for easy flicking at prey) and external eardrums right behind their eyes.

The peepers born later this spring will spend most of the summer in the water as tadpoles. If they are extremely fortunate and avoid becoming lunch for some other animal, they will mature, lose their tail, and move to land. Then they will spend three or four years as “pre-teens” before being able to reproduce.

Since peepers are cold-blooded, a sudden freeze will temporarily silence the swamps. But the peepers and some other frog species are quite tolerant of cold, having a high level of glucose in their tissues and being capable of surviving temperatures as low as 17 degrees F for up to two weeks. I suppose this would make them quite tasty to eat, so it’s a good thing they’re too small to be worth the hunting.

The best places to hear peepers are small, shallow bodies of water or swamp that warm up quickly, such as those found along the Norwottuck rail trail, the swampy areas around Lake Warner, and along the wonderful accessible boardwalk paths of the Silvio O. Conte Nature Trail in Hadley.

Almanac is a regular Indy column of observations, musings, and occasional harangues related to the woods, waters, mountains, and skies of the Pioneer Valley. Stephen Braun has a background in natural resources conservation, which mostly means he is continually baffled by what he sees on explorations of local natural areas. Please feel free to comment on posts and add your own experiences or observations. You can also email at: braun.writer@gmail.com.

Sometime each year, around mid-March, there’s a village in rural northern Chester County, Pennsylvania, that closes its main drag to traffic, as the first warm rains bring millions peepers from the nearby forests to frolic in pools near the Birchrun, the creek after which the village is named, and in whose whose valley all this friendly — or fisticuff-ly?! — frolicking is found.

It’s best of this first warm rain is at night, and quite heavy: when walking with a flashlight, it’s difficult to distinguish big droplets bouncing off the pavement from fecund frogs hopping across the road — could that be how they’ve came to have their backs marked with the cross? Sounds a Just So Story, but begs a bit of (super-sweet? 😉 food for thought how their crossmarks actually evolved.*

====================homework==================

*The selective value of camouflage from birds in twiggy trees might be a better explanation for these tree-dwellers’ crossmarks — far fairer than other seasonal symbolic coincidences a fertile mind might fancy — though twigs do grow into tree branches….

Splendid nature writing, Steve! Thanks so much for seeing as you see (and hear), and for writing about it here.

Thank you Sarah…glad you’re enjoying the column! I’m enjoying writing it! And Rob, thanks for the tidbit about Birchrun…reminds me of our local efforts on Henry St. to create safe passage for all those spotted salamanders on the move in the spring.

Love this series — and love spring peepers.