Almanac: Over the Dam

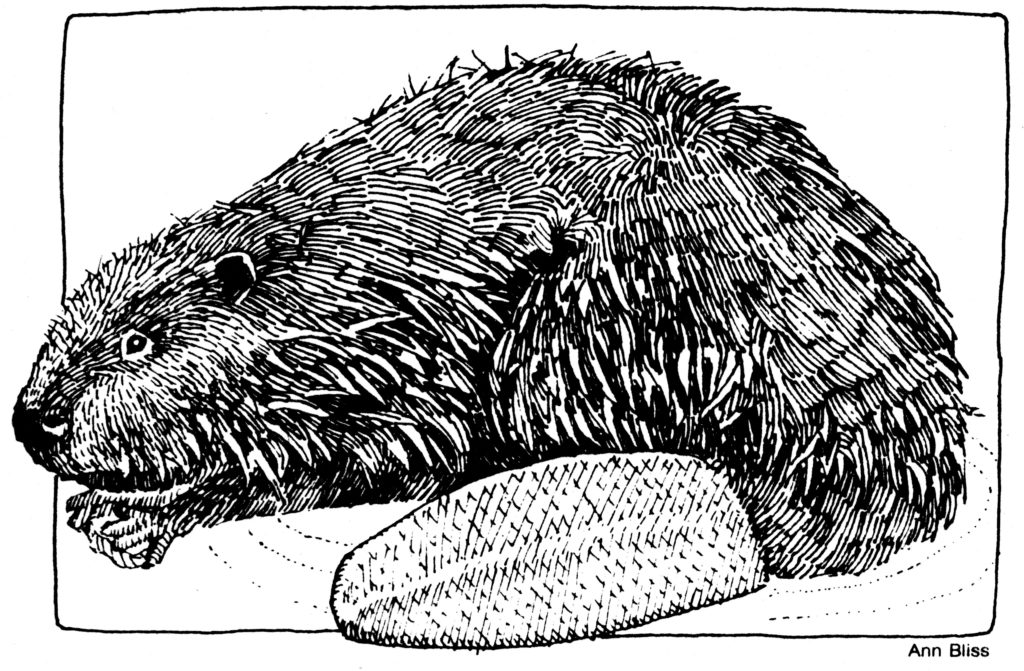

Drawing: Ann Bliss

About a decade ago I built a 14-foot wooden kayak. It’s an attractive chestnut-brown boat If you don’t look closely enough to notice its myriad imperfections. Several years ago I spent four days kayaking the Allagash river in northern Maine. The Allagash is relatively shallow and runs, sometimes wildly, along a boulder-strewn course. After three days of bashing against and over rocks in the course of navigating rapids, the bottom and sides of my boat looked as though it had been mauled by a grizzly bear.

My companions and I had hauled out for the night at the end of day three when an old French Canadian river guide named Norman L’Italienne came by to chat. When he spied my boat, he rubbed a grizzled chin thoughtfully and said, with a thick French-Canadian accent, “Ay, that’s much too pretty a boat for this river. For this river you need a boat made of Tupperware.”

The old guide’s words echoed in my head last week as I contemplated my next move on another mountain river. This time I was paddling up the meandering inlet of Big Moose Lake in the Adirondacks. After a couple of miles my passage was blocked by a magnificent beaver dam roughly 40 feet wide and three feet high. Sitting in my kayak below the dam I could see, almost at eye level, the surface of the pond behind the dam.

I knew the stream beyond the dam became quite rocky and relatively shallow, which is why, on previous trips, I’d never attempted it. But the dam raised the water level considerably, so now I was tempted. Should I try to haul my boat over the dam and explore the stream, or return another day with a Tupperware boat? Hmmm…

It was a lovely morning, with color coming already to some of the red maples and with the deep quiet of the wilderness surrounding me. So I dawdled and admired the dam.

On planet Earth only two other species, Homo sapiens and coral, can alter their physical surroundings as dramatically as beaver. This is why beavers are called a “keystone” species—they create entire ecosystems in which diverse communities of plants, animals, insects, and invertebrates can thrive.

Adirondack beavers were nearly exterminated in the “beaver fever” of hunting and trapping that did, in fact, completely wipe out beaver populations in Massachusetts and other New England states in the 17th and 18th centuries. By 1900 it is estimated that in the entirety of New York state only one or two beaver families living near Saranac Lake survived. But by 1900 fashion tastes had shifted away from fur garments, the supply of beaver pelts had plummeted, and a new ethic of conservation was taking root. The existing pocket of beavers was protected by law and some private landowners began reintroducing small numbers of beavers from as far away as Yellowstone Park. The beavers thrived. By 1915 the state population was estimated at 15,000, and in 1923 New York considered the population healthy enough to allow trapping once again. The current population of Adirondack beavers is estimated at 50,000 to 70,000.

Entire books have been written about beavers, their astonishing abilities, and the ways those abilities sometimes conflict with humans. Here I’ll just focus on the question circling in my brain as I pondered whether to surmount the dam in front of me, namely: how the heck can these critters build structures so sturdy they can survive for decades despite periodic floods?

Although beaver dams usually look like a jumble of loose sticks they are, in fact, carefully and continually crafted from rocks, mud, and sticks. Beavers usually start building a dam from one side of a stream, laying down a base of large rocks. Then they start adding sticks, held against the rocks by the current. The sticks are not randomly chosen nor randomly placed: some species, such as alder and birch, which are flexible, are preferred and these are woven together to form a loose net-like structure. After that the beavers start plugging holes with smaller sticks, vegetation, moss, and mud. They keep building until the water behind the dam is high enough to provide them the protection from predators that is the main (but not sole) function of the dam.

Dam-building appears to result from both genetically-driven instinct (the details of which remain mysterious) as well as learning. Young beavers, called “kits,” typically spend two years after birth helping their parents build and maintain dams as well as the similarly-constructed lodges, learning the tricks of the trade as they grow. I’m more than a little gob smacked by this because it implies that these seemingly-simple giant rodents possess exquisitely complex and sophisticated minds finely attuned to nuances such as water depth, the sound of water leaking through a breach in a dam, and the size and quality of the sticks required for building.

In the end, my curiosity about what lay above the dam overpowered my uncertainties about stepping on the sharp, pointed sticks of the dam and the risks to both me and my boat involved in summiting the dam and navigating a potentially rocky stream. It turned out to be easier than I thought. The dam was rock-solid underfoot with a nice, soft accumulation of sand and mud behind. I managed to drag the boat over and get back in without an inglorious dunking. The higher water level did, in fact, allow passage upstream for another half-mile to a lean-to campsite, beyond which the stream became way too thin and rocky to navigate without risking another mauling.

About halfway up the stream I encountered a much smaller and incomplete dam, only about 12 feet wide, and mostly submerged. I powered over it with a few hard strokes and didn’t think more about it. The next day I brought a friend along for a repeat trip. We both surmounted the main dam and all was well until we encountered the small dam farther up. I was amazed to see that overnight the beavers had added enough new branches to the dam to utterly confound our forward progress. I tried yanking some of the sticks out, but they were so firmly embedded in the rest of the dam that I gave up. We admitted defeat and turned around, but not without a grudging admiration for the skills and energy of these amazing creatures.

“Almanac” is a regular Indy column of observations, musings, and occasional harangues related to the woods, waters, mountains, and skies of the Pioneer Valley. Please feel free to comment on posts and add your own experiences or observations.

Steve’s column has become the first Indy article I read each week! Always fascinating with new (to me) knowledge.

Hilda beat me to it this week, but I, too, am … “gob smacked”!

Fascinating, Steve! I love the evocative prose that allows us readers to journey along with you. Love the photos too!