Almanac: Flash Powder

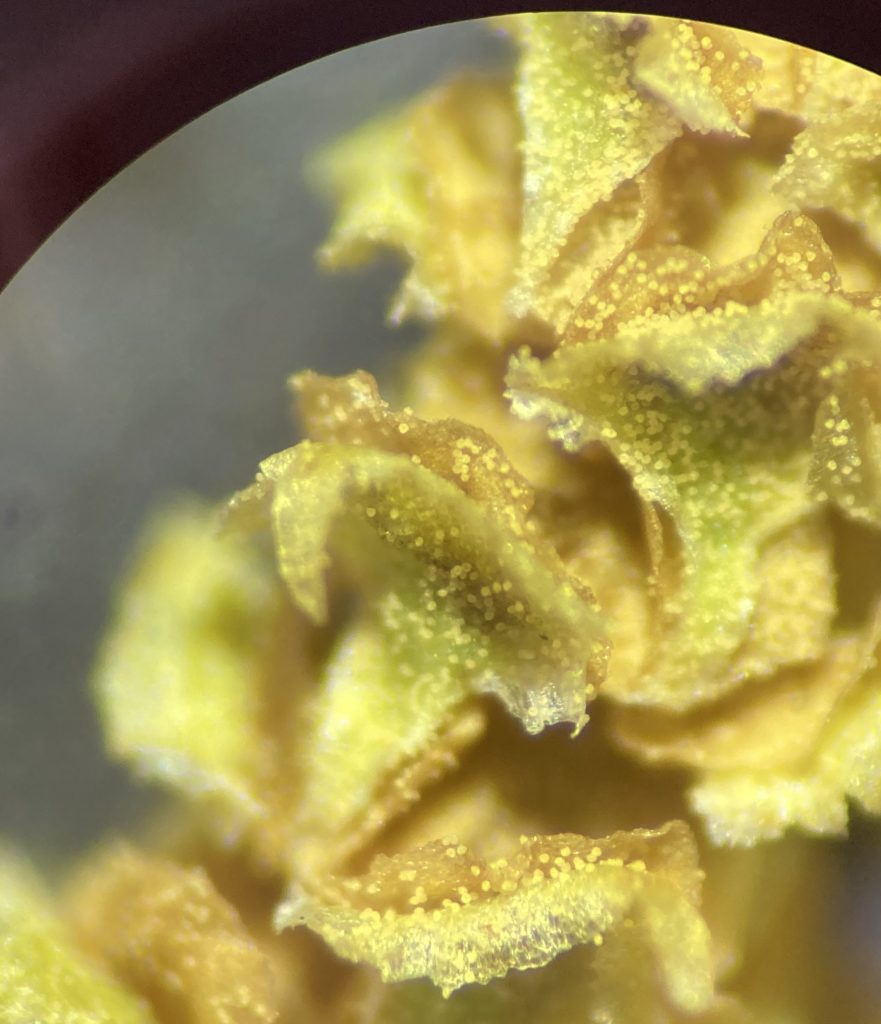

Club moss, or lycopodium, with spore-bearing stalks, or strobili. Photo: Stephen Braun

The all-enveloping green of summer is gone. With the deciduous trees bare, the grasses brown, and the forest floor covered with old leaves the wide-view scenes on walks and hikes is predominantly the late-fall palette of gray/brown/black. This nearly monochrome background, however, serves as a perfect contrast for the few remaining green plants to pop out visually. On a walk along the Pocumtuck trail recently the still-green leaves of mountain laurel, Christmas ferns, and sometimes shockingly green moss all caught my eye as they seldom do in summer.

Among the keepers of summer green is a small, usually inconspicuous little plant with a rich history and curious nature. I came across carpets of these plants up on the Pocumtuck ridge, their scaly pine-like fronds standing out starkly against the dull leaf litter, and many topped with the distinctive spore-bearing spikes that lend the plants their general common name: clubmoss. The name is a misnomer—these are not mosses at all. They are true plants, with roots and sophisticated vascular systems to transport water, minerals, and nutrients. They are also ancient, having evolved roughly 410 million years ago, far earlier than the reign of dinosaurs.

There are around 20 species of clubmosses in New England, with common names like princess pine, ground pine, and ground cedar. Because clubmosses are so beautifully green and easily harvested they were once a popular component of holiday wreaths and garlands. But over-harvesting took a toll. These plants grow very slowly, and primarily by simple spreading of the roots, or rhizomes. It’s estimated that a colony 100 square feet in size may take a century to grow.

The cool part of these plants are the pale-yellow microscopic spoors produced in spike-like structures called strobili. About 2 to 4 strobili are usually clustered at the tip of a green, branching frond. The sporulating season tends to be from July to October, but I found numerous strobili in various stages of maturity, some very tight, others opened up and releasing little plumes of spores at the slightest touch.

The genus name of many clubmosses is “lycopodium,” hence the spores are called “lycopodium powder.” The spores can be collected relatively easily without harming the plants and, in fact, this is done on a large scale and tons of lycopodium powder are sold today for a variety of uses, both medicinal and industrial.

The most interesting characteristic of lycopodium powder is its extreme flammability. This is due both to the tiny size of the spores and their high oil content. Lycopodium powder was used as “flash powder” in the early days of photography, and has also been used in magic acts and for theatrical and cinematic special effects because the resulting flames are very short-lived and relatively cool.

The spores are not at all dangerous (although you should avoid inhaling them) because they are only flammable when dispersed in air. A pile or jar of lycopodium powder will simply sit there if you put a match to it. But a puff of powder over a candle or other small flame produces an impressive fireball.

The flammability of lycopodium powder has been known for centuries. (One wonders, as with many things, what kind of accident or coincidence set the stage for this discovery.) This is why, in 1806, the brothers Claude and Nicéphore Niépce, living in Nice, France, chose lycopodium powder as the fuel for what became the first working, patented internal combustion engine. They called their primitive engine a Pyreolophore (combining root words for “fire” “wind,” and “produce”). They first used their engine to power a boat. About 12 times a minute a smidgen of lycopodium powder was injected into a stream of air that brought it to a combustion chamber where it was ignited by a smoldering fuse. The expanding gas pushed a piston which forced water out of a tube from the back of the boat, propelling it forward in a series of smooth jerks. The engine worked well enough to be patented, in 1807, but because lycopodium powder was relatively expensive, the brothers switched to pulverized coal in later models.

Lycopodium powder has other curious properties, such as being extremely hydrophobic. If you sprinkle a layer of powder on a glass of water and stick your finger in the water, the powder will coat your finger so completely that it’s as though you were sticking your finger through a piece of very flexible saran wrap. Remove your finger and it is perfectly dry, albeit with a light coating of spores. This property was used in many ways in the past, such as to provide a lubricating dust on skin-contacting latex goods such as condoms and surgical gloves or for covering pills.

I collected a bag of strobili on my walk and am waiting for the spores to be released so that I can do a little careful experimentation with the flammable aspects of lycopodium powder, both because I’m curious and because I’m a closet pyromaniac. I’ll report my results, for better or worse, in a later column. Meanwhile, keep an eye out for these vestiges of summer green on your walks in our local woods.

Almanac is a regular Indy column of observations, musings, and occasional harangues related to the woods, waters, mountains, and skies of the Pioneer Valley. Please feel free to comment on posts and add your own experiences or observations.

1 thought on “Almanac: Flash Powder”