Life Under ICE: Surviving and Organizing amid a New Immigration Regime

Illustration: Charles Forsman

by Dusty Christensen

Federal agents have already disappeared some living without legal status in western Mass; for others, fear pervades.

The following article appeared originally in the Shoestring on August 19, 2025. It is reposted here under a Creative Commons license. .

Shoestring editor’s note: The Shoestring has granted anonymity to several sources in this article.

It was a regular spring morning for J. and her family. That is, until one of her kids burst into the room in a panic. Masked immigration officers had just grabbed her husband right outside their home in western Massachusetts.

“Mom, hurry up,” J. recalled her child telling her. “They threw him to the ground and got on top of him.”

It was a possibility that J. and her family knew existed, given that her husband is an undocumented immigrant from Mexico. Two days prior, they had talked about what they would do if Immigration and Customs Enforcement arrested him. But she never thought that ICE would grab him off the street as he walked to the car with their son to take him to school.

As she ran outside, J. saw officers surrounding her husband. She said the federal agents refused to identify themselves, telling her only that her husband would have the right to a phone call after he was processed at a detention center. They stuffed him into a car and drove away, leaving behind J. and her suddenly separated family.

“I was left so confused, so lost in that moment because I didn’t know what would happen,” J. recalled. “My only instinct in that situation was to yell to ask if anyone recorded anything and if they could help me.”

Eventually, she went back inside and, together with her kids, started to cry.

Seven months into the administration of President Donald Trump, many immigrant families have experienced the same across Massachusetts. In May alone, ICE boasted that federal agents had arrested nearly 1,500 immigrants in the state. Videos and eyewitness accounts have emerged of officers following immigrants as they dropped off their kids at school, smashing windows to yank people out of their vehicles, and arresting others at previously off-limits locations like courthouses.

Often, federal agents are wearing military-style tactical gear and covering their faces. Their increased presence on the street has drawn the anxious attention of immigrants and citizens alike — people like bystander Matt Gagnon, who witnessed officers arrest two people working for a roofing company in Easthampton last month. Agents had pulled over the workers’ van.

“There was one moment where the driver looked over at me and I could see the fear in his face,” Gagnon told The Shoestring.

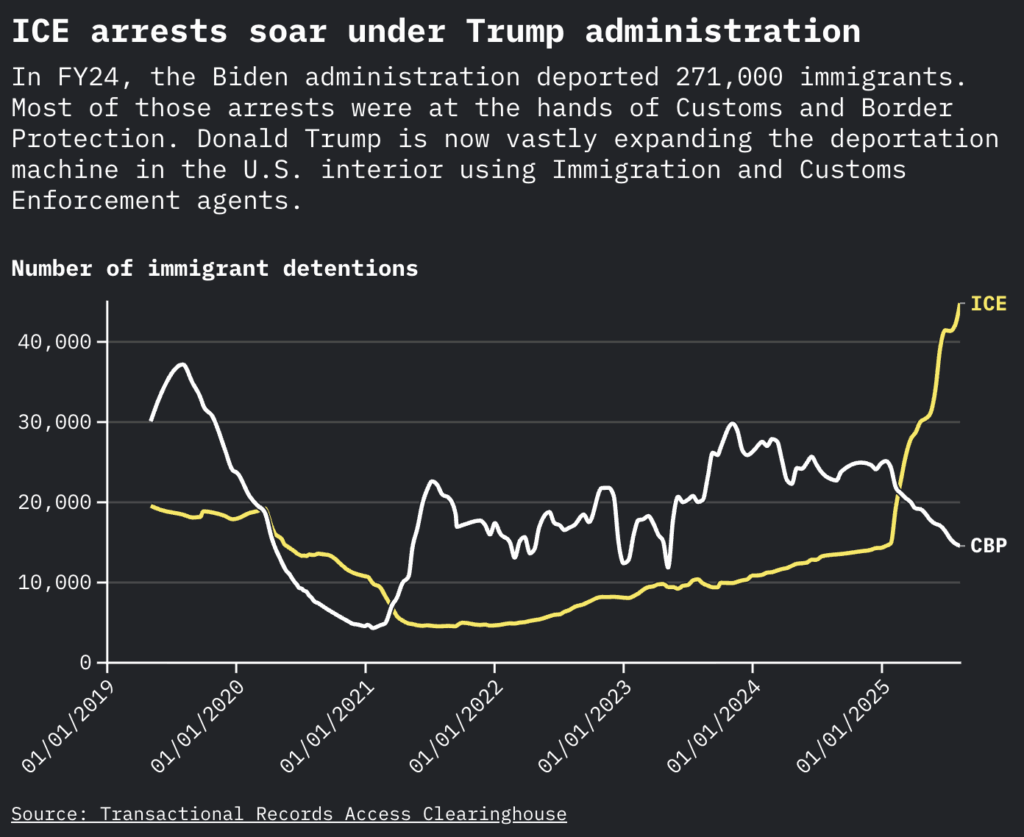

It’s all part of the promises Trump and fellow Republicans have made to carry out mass deportations at unprecedented levels. Previous presidents, both Democrats and Republicans, have set deportation records in recent years. In fiscal year 2024, for example, President Joe Biden’s administration deported 271,000 immigrants — more than any year over the previous decade. Most of those deportations came after arrests by border agents. But Trump is looking to further grow the country’s deportation machine in the U.S. interior, too. Earlier this week, The New York Times reported that 60,000 immigrants are now in immigration detention across the country, which represents a modern record.

Those detentions look likely to continue growing in number. Earlier this summer, Republicans passed a budget bill that will give the deportation agenda a massive infusion of funding: $170 billion to be spent, over four years, on hiring more immigration agents, building more detention facilities, and expanding the powers of ICE.

The result has been a pervasive sense of dread in immigrant communities in western Massachusetts, according to interviews The Shoestring has conducted with immigrants and their allies. But community members have also organized mutual aid networks to help each other survive under the new immigration regime.

“It’s a huge fear that we’re living with,” said P., an undocumented farmworker who left El Salvador more than 20 years ago to escape gang violence and to search for a better life in the United States. She has worked across the east coast, from chicken farms to tobacco fields, and now lives in western Massachusetts. She said she knows many people who have had a family member detained. “People are afraid to go to the store, to go wash their clothes.”

In particular, P. said that immigrant workers — who already lead difficult lives doing low-paid, essential jobs that keep society functioning — have no choice but to carry on with their lives. But now, she looks at every car on her street and can’t help but feel paralyzed with anxiety when one stops. She asks herself: “Is it ICE?”

A single mother herself, P. said children in the immigrant community are particularly scared living under the threat of deportation. She’s had to talk with her own son, who is a citizen, about what would happen if she’s arrested while he’s at school. She’s left his documents with someone she trusts who could take him to school or the doctor, for example. Eventually, she’d have him sent back to her in El Salvador, despite the fact that the United States is the only country he has ever known.

“The kids are traumatized because they’re so worried,” she said.

***

That reality is perhaps most obvious in the region’s schools.

Javier Luengo-Garrido has been working to protect the rights of immigrants in Massachusetts for the better part of the last decade. As the American Civil Liberties Union of Massachusetts’ deputy field director for regional engagement, he and his colleagues have put on more than 100 “know your rights” trainings since January for more than 3,000 immigrants statewide.

Luengo-Garrido said that educators are in a unique position to see the impacts that living under the shadow of ICE is having on children.

“What we’re hearing from teachers, from administrators, people who are really really close to families… is that many times they are seeing a drop in attendance for students,” he said. “Which is absolutely understandable.”

The superintendent of Berkshire Hills Regional School District told The Berkshire Eagle in April that school attendance had dipped amid fear from recent immigration arrests in the area.

“With schools starting soon, there’s a lot of fear in sending children back to school,” J. told The Shoestring.

The Shoestring relies on reader support to make independent news for western Massachusetts possible. You can support this kind of labor-intensive reporting by visiting our DONATE PAGE.

A handful of local municipalities, from Northampton to Springfield, have passed different versions of ordinances in recent years affirming their status as a “welcoming community” or “safe city” for immigrants. They limit how police and other municipal agencies can interact with federal immigration authorities or whether they can ask a person’s immigration status. Luengo-Garrido explained that the idea is to ensure that immigrants feel comfortable reporting that they’re the victims of a crime to law enforcement, for example, or to report poor housing conditions.

“What’s happening now is people are really fearful to do those kinds of things,” he said. That means that survivors of domestic violence or sexual assault may be hesitant to report those crimes to a police department, fearing the department may be cooperating with ICE, he explained. “That’s highly concerning, and certainly this administration has made the immigrant community really fearful to engage.”

Luengo-Garrido said that the big differences between Trump and previous presidential administrations is the scale of deportations and the level of physical violence agents are using.

“The visibility and the way how this is happening in the middle of the day certainly generates fear among community members,” he said. “You can argue that a lot of the operations that are being done in the middle of the day are not only to make the detention effective but it may also be sending a message.”

As for the exact number of detentions that ICE has made in western Massachusetts, Luengo-Garrido said it’s hard to say.

But immigrants are also pushing back in their own ways, from legal-rights trainings to creating networks to alert each other that ICE is operating in a particular area.

In western Massachusetts, the Pioneer Valley Workers Center has been on the front lines of that work. As an immigrant-led collective, the center’s organizers began seeing a lot of misinformation early this year circulating on social media, and by word of mouth, about ICE’s actions. They saw this as part of immigration agents’ fear tactics, meant to encourage people to self deport and to divide the general public to keep them from organizing against deportations.

“We were really clear that we needed to combat misinformation and get people real facts,” said a representative from the workers center who requested anonymity for this article. “So that they could be making risk assessments about how to go about their lives based on that information as opposed to the misinformation that was being fed to all of us … People make decisions like not leaving their homes, wondering if they should send their kids to school, or whether to go to a medical appointment.”

So, together with other immigrant-led grassroots organizations, the Pioneer Valley Workers Center co-founded the LUCE Immigrant Justice Network of Massachusetts — an organization that operates a hotline people can call at 617-370-5023 to report ICE sightings. LUCE has also trained a team of verifiers who go out onto the street to confirm those sightings, meaning that anyone can get up-to-date information about the presence of immigration agents in their communities in as little as five or 10 minutes.

“This is not the time to fall into fear and complacency,” the workers center representative said. “It is by design that many of us are afraid, in some cases shocked, and want to stay small and quiet in these moments. This is not the time to do that.”

Groups like the Pioneer Valley Workers Center have also been organizing across the state to help directly impacted people in other ways, like holding know-your-rights trainings, assisting with “family preparedness” documents to prepare for the worst, and working with people to locate detained loved ones and then navigate the post-detention process. They’ve raised money for separated families and organized rides to people who need to get to an appointment.

***

Asked what message she had for Americans, P. said she wanted people to know that immigrants work hard — on farms, for example, doing jobs that citizens won’t do. She said she’s been to the Massachusetts Statehouse before to talk to lawmakers about protecting immigrant rights and changing the state law that allows bosses to deny farmworkers overtime pay.

“You feel awful when you go and they don’t pay attention to you,” she said “I want to tell them, ‘We work so that you have your fruit and vegetables fresh on your tables, so your kids and you can have organic produce … Where do you think that comes from? Who do you think harvested that?’”

Behind that plate of food, P. said, is a parent like her who had to leave their kids with someone else at 4 a.m. to go into a wet field, where they’ll work soaking for the entire day. They often don’t get home until 6 p.m., and even then they can’t enjoy spending time with their kids. They shower, cook, help them with a little homework and then put them to bed. They’ve got to wake up early the next day, after all, and do it all over again — sometimes six or seven days a week. During the summer, P. said she doesn’t often get the chance to take her son to the playground like other families.

“Take some time and read our stories,” she said. “We didn’t come here to be enemies. On the contrary.”

P. said she hasn’t lived through family separation but knows plenty of people who have been taken away from their spouse or child. The result, she said, is devastating.

“You can’t go outside freely, go play in the park,” she said, because of the worry that ICE will be there. “And just because you’re Hispanic and they see your skin, they’ll say, ‘That’s the person I’m going to take because they’re doing something bad here.’”

As for J., when ICE detained her husband earlier this year, she remembers her parental instinct taking over while crying with her children. She decided it was time for action, and she had only one goal for that day: find out where they took her husband. So she went to the police, then to district court, then to the office of a lawmaker. She learned that immigration agents were taking him to several stops before his ultimate destination: a detention facility in Rhode Island.

“The best I way I can describe it, the first few weeks I was in survival mode,” she said. “I had lots of anxiety, lots of stress, I had lots of nightmares. In one, I dreamed that immigration was taking me and I was screaming, ‘My kids! My kids!’ I woke in a panic.”

Over the course of a month, she would regularly call her husband. But the day she didn’t call, he was suddenly transferred to Texas — a process she said left her husband with intense anxiety.

Eventually, her husband had his court date and was released back home. The family is now in the process of applying for a green card for him, which they had begun to do before his arrest. It has been a difficult endeavor, she said. But as a citizen herself who was born and raised in the United States, J. said she can’t imagine how hard it would be for someone who didn’t speak English.

And the nerves still remains.

“Although he’s not detained now, I’m always worried that they’re going to take him again — that immigration is going to arrive again,” she said. “You feel like you’re on their radar. They’re watching you and can show up whenever.”

“We still have a long road to travel.”

Shelby Lee contributed reporting to this story.

Dusty Christensen is The Shoestring’s investigations editor. Based in western Massachusetts, his award-winning investigative reporting has appeared in newspapers and on radio stations across the region. He has reported for outlets including The Nation magazine, NPR, Haaretz, New England Public Media, The Boston Globe, The Appeal, In These Times, and PBS. He teaches journalism to future muckrakers at both the University of Massachusetts Amherst and Smith College. Send story tips to: dchristensen@theshoestring.org.