Opinion: Human Rights Day in Amherst, 2025

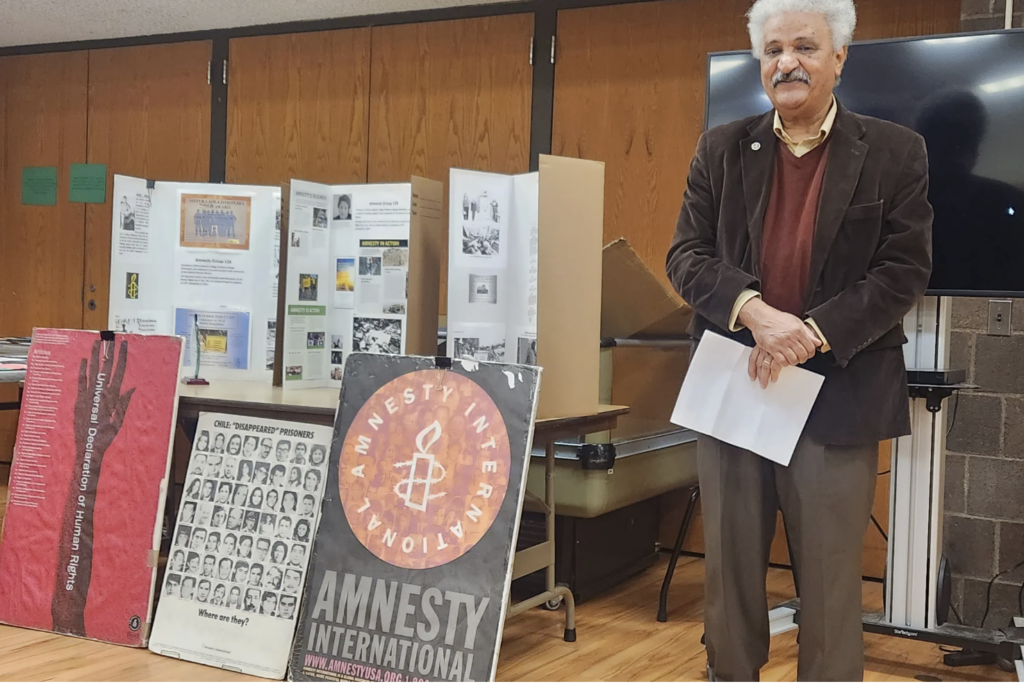

Mohd Elgamil , representing Amnesty International spoke at Amherst's 2025 Human Rights Day. Photo: Rizwana Khan

Social Injustice Goes Global

Where the Global Finally Felt Local

Human Rights Day in Amherst this year did not feel ceremonial but inhabited.

On Wednesday evening at 5:20 p.m., the Bangs Community Center filled not with slogans but with families, middle school students, elders, activists, town staff drawn together not by outrage alone, but by recognition.

Organized in collaboration with the Town of Amherst DEI Office, the Amherst Human Rights Council, and Amnesty International.

The reinstatement earlier that year of guidance counselor Delinda Dykes, who had been fired in 2023 for discrimination against LGBTQIA+ students, lingered not as vindication, but as a reminder that protections for LGBTQ+ students at Amherst Middle School, even in a community that values inclusion, remain hard-won and require continued vigilance.

What made the evening feel rooted in was not the speakers’ credentials, but the children. Middle school students from Amherst had spent weeks studying the 30 articles of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights as part of their curriculum. Each article was translated—not summarized—into original artwork.

The walls of the community room disappeared beneath drawings of hands breaking chains, doors left ajar, families reunited, borders crossed, bodies protected. A visual constitution, filtered through young minds still untrained in euphemism. This wasn’t abstract pedagogy but interpretation as ownership.

Mohd Elgamil has been coming to the Amherst Farmers’ Market for nearly two decades. That history mattered on Human Rights Day in Amherst 2025, because he wasn’t arriving as a guest lecturer but already part of the town’s muscle memory. Representing Amnesty International, Elgamil did not raise his voice or dramatize his past. He told that in 1992, he was imprisoned in Sudan for 118 days without trial, held in what are known as “ghost houses”—unofficial detention centers designed to erase people without paperwork, witnesses, or clocks. He was released only after an Amnesty International chapter in England sent a letter demanding his freedom. After six months in detention, he said, a small package arrived and inside was a single pair of underwear.

The room went still.

The detail mattered because it collapsed the distance between policy and flesh—between “arbitrary detention” as a phrase and the body that must endure it. His gentleness unsettled the audience more than anger could have. Middle school students listened closely, their artwork lining the walls now reframed: not symbolic, but evidentiary.

Elgamil mentioned two lawyers who were spared execution after years of international pressure—not because governments suddenly grew merciful, but because sustained documentation made them afraid. Amnesty kept the light on and the governments blinked.

Seven members of the Amherst Human Rights Committee sat in the front and then several students stood to speak, explaining what human rights meant to them. The program continued with a collective reading of the Universal Declaration—each attendee voicing one article from a three-page handout. Thirty articles, thirty voices and no hierarchy.

The evening closed with a screening of a webinar produced by the Amherst Human Rights Council in partnership with Amherst Media. Cookies and juice followed, conversation lingered and no one rushed out. For once, human rights didn’t feel like an export.

The Campus Just Up the Road

And yet, just miles away, UMass students could tell you what happens when rights meet power.

As Amherst’s middle schoolers were illustrating the Universal Declaration, last year UMass students were beaten, arrested, and charged for exercising the very rights those articles enshrine—assembly, speech, conscience. The contrast was not ironic but structural.

Human Rights Day asked participants to read aloud promises made after World War II— “never again,” accountability, dignity, restraint. The university had answered those promises with barricades, batons, and handcuffs.

This dissonance—between civic ritual and institutional practice—has become the defining feature of American human rights discourse.

At Bangs, democracy was the sound of paper rustling as students passed the Declaration but like a soft voice recounting imprisonment without spectacle. The applause didn’t sound triumphant but affirming like people who know the words by heart but are still waiting to see whether anyone with power will honor them.

Human Rights Day in Amherst mattered this year because when middle school students draw freedom on paper while university students are punished for demanding it; when a town celebrates inclusion while staff and students fear retaliation; when a man freed by a letter from England speaks softly to children who are learning what dignity looks like—the abstraction collapses.

Human rights are no longer something that happens “over there.” They are negotiated in community centers, on campuses, in comment threads, and in courtrooms and are tested not by declarations, but by response.

Human Rights Day didn’t solve Amherst’s contradictions, but that democracy survives when practiced and is not branded.

Mohd Elgamil will be back at the Farmers’ Market next season, alone holding banners and adding names to lists that grow longer than the world contracts. There is no stage, no microphone with Elgamil, quietly asking people to sign.

Twice a month, all four seasons, he stands alone with his banners—handmade, sun-faded, carefully lettered—bearing the names of causes most people scroll past on their phones. Sudan. Palestine. Myanmar. Bangladesh. Egypt. Ethiopia. The list keeps growing, and so do the clipboards anchoring a global ledger of injustice in the middle of a Saturday morning ritual of sourdough, apples, and local honey.

And that, more than any press release, is what human rights look like when they’re real. more than any policy statement and that where the story now lives.

But The Global Frame Cracks

When the world emerged from the horrors of World War II, it built an architecture of international justice intended to outlast political whims. The International Criminal Court, human rights treaties, independent documentation bodies were meant to ensure that genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity would not be met with silence.

Today, that architecture is being deliberately dismantled.

On September 4, the Trump administration-imposed sanctions on three leading Palestinian human rights organizations:

- Al-Haq, founded in 1979, a pioneer in documenting violations in Gaza and the West Bank

- Al Mezan Center for Human Rights, which for over two decades has meticulously chronicled laws-of-war violations in Gaza

- The Palestinian Center for Human Rights, long known for providing legal aid to victims, particularly from Gaza.

Earlier, in June, the administration sanctioned Addameer, another leading Palestinian rights organization.

These were not fringe groups but central nodes in the global human rights ecosystem—organizations that have worked closely with Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch for decades. Their crime was not violence, but documentation. Their offense was cooperation with international law, including submissions to the International Criminal Court regarding Israeli conduct.

The Trump administration slashed funding to the United Nations, withdrew from the U.N. Human Rights Council, terminated most U.S. foreign aid supporting human rights defenders, and gutted grants through the State Department’s Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor. Programs supporting refugees, women, and global justice were quietly erased.

The message was unmistakable: human rights are conditional, and accountability is optional—especially when powerful allies are implicated.

Sanctions disrupt operations and chill speech. They warn every human rights defender watching that evidence itself can be criminalized.

The International Criminal Court—created in 1998 as a court of last resort—was designed precisely for moments like this. Imperfect but essential, it exists to interrupt cycles of abuse by asserting that even the highest offices are not immune. Sanctioning those who cooperate with the court threatens victims everywhere, not just in Gaza.

Governments that helped establish this system now face a choice: defend it or quietly dismantle it.

Rizwana Khan is a writer, educator, and human rights advocate in the Town of Amherst.