Views on Views: Conservatories, Greenhouses and Roof Gardens

Camellia bushes at Durfee Conservatory, UMass Amherst, 2023. Photo: Hetty Startup

By Hetty Startup

This is the seventh column in a ten-part series. View the previous articles in the series here.

So far, I’ve covered landscape design from a number of perspectives such as the importance of roads/rivers; the presence of our public parks and our town trails; the significance of our stone walls; our town’s shade trees, and our permaculture gardens. The article on shade trees may even have helped instigate the Town’s Shade Tree Committee’s new series of articles about their ongoing work (see also here).

I have tried to stick with what is publicly accessible in terms of examples of landscape design, even though I know there are hidden treasures we may never see in the backyard gardens of townsfolk. My evidence is based on the garden tours that the Amherst Historical Society has hosted in the past although perhaps not since the pandemic – and the public tours – often to support Amherst Neighbors – or the Garden Conservancy at the Kinsey-Pope Garden on High Street.

At this time of year, with snow on the ground and cold temperatures, walking outside can be a magical treat, but it also makes sense – and perhaps is advisable, and safer – to set one’s sights on some indoor activities. Perhaps like a neighbor of mine, you have reclaimed your three-season porch? Friends of mine in Ashfield love their sunny window seat where they can watch the sun setting.

Most winters, I ‘force’ some flower bulbs in water, in what are called hyacinth glasses, maybe adding a bit of charcoal to the glass. This-long-standing ritual mimics the expectation of spring being ‘round the corner’ – an old habit much-heralded by generations of university co-op extension programs or social media mavens like Martha Stewart. As a tradition, this activity goes back to the 17th century (the 1600s), and, over time, the Dutch made this horticultural pastime into a fine art, “tickling” flowers into bloom in ornamental vases as well as table or mantel centerpieces. It is always my ‘cast of mind’ to look historically at trends and rituals like this but another winter ritual brings you, gentle reader, right up to date. I used the recent storm to make homemade marmalade as a gift for family and friends, savoring the warm, citrusy aroma of Seville oranges simmering on the stove.

Like many of you, as we move into February and March, I will be nursing some seeds to plant outside later on. On a domestic scale, this is modest stuff, I realize, but it appears that there are a number of strategic steps that landscape designers, past and present, have taken that honor these very human desires to bring the outside in, nurturing nature, if you will, indoors.

To be sure you catch my drift, I’m sharing information about some local conservatories, greenhouses, and roof gardens. About a month or two ago, the Indy’s Photo of the Week featured a picture I had taken of the stands of espalier fruit trees near the Durfee Conservatory on the UMass campus.

As it happens, Durfee’s buildings date from 1867 and house a dedicated Bonsai-Camellia House that, at this time of year, features historic camellia trees blooming in shades of red, pink, and white. When I visit, I am reminded of seeing the large camellia trees inside an orangerie at Holland Park, in London.

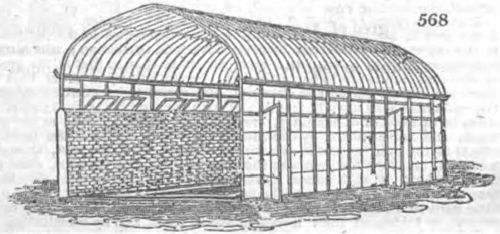

An orangerie is a high-style, architectural structure designed centuries ago to support the growth of tender plants such as orange trees in places like France, famously at Versailles, where an orangerie was created to house the plants over the winter. Initially, due to the cost of sheets of glass, these fancy structures in the landscape were seen as a luxury design feature, protecting fruit trees owned by the nobility. It had been the Italians, in places like Padua, who had invented them during the Renaissance. By the 1700s, the Dutch had perfected neo-classical versions using red brick and large expanses of windows. The insides had to be heated with wood stoves that were tended by gardeners and estate ‘hands’. In the 1800s, technological advances and the desire to create specific microclimates for plants from all parts of the world proliferated in New England. Fancy greenhouses or glasshouses began to have glazed roofs to maximize sunlight. They were popularized here by Scottish architect and landscape designer, J.C. Loudon. Some of the first ones in America were designed for estates near Philadelphia.

Closer to home, I believe the nearest orangery to Amherst is one at Tower Hill in Boylston, MA, at New England Botanic Garden.

Even if an orangerie was beyond your reach in the 1800s, you could create one at home, something called a Wardian Case – a small table-top glasshouse, filled with tropical plants. And by then, if you were well-off, you could buy oranges. These are native to the Middle East and were initially shipped from Ottoman-ruled Palestine, where they were grown by Arab farmers. The most famous orange was the sweet Jaffa orange, the Shumouti variety, which had a tough skin, making it less vulnerable to spoiling in transit. Over time, both Arab and Jewish shippers packed them in tissue paper wrappers, a memory from my youth.

Getting back to Amherst and to UMass, another landscaping feature that can offer access to nature and the natural world in a different way is the creation of a roof garden. There’s a really nice one at the LEED Platinum-designed John Olver Design Center that is a green roof terrace and forms part of what is termed layer planting, both inside and outside this special building. Take the elevator to the top of the Olver Center or link to a tour here. Roof gardens were advocated by the modernist architect Le Corbusier as a way of returning a piece of the earth to the top of a new building that, by its siting, had necessarily removed land to form a foundation. It had—and continues to have—other benefits too.

One really stunning example of a roof garden is that of the Gropius House, in Lincoln, MA, where Walter Gropius, a contemporary of Le Corbusier, created a unique space to catch warmth and light (indeed a veritable light show) on the top floor of his home, built in 1938-9. \

In Amherst, in the dead of winter, standing at the window and looking at the snow, with a mug of tea warming my hands, I realize that the most interesting aspects of architecture and landscape design are sometimes to be found at its intersections, where inside and outside meet.

Remaining articles in this series will address: (8) Fountains and waterways; (9) Garden follies and lighting; and (10) Amherst’s hard-working Conservation Commission.

Indy readers may know that I sometimes include poems in my articles if they add – or confirm – a larger idea or theme. I am hoping a recipe – in this piece – serves a similar function, shifting the focus of comprehension from words to another way of seeing. Understanding how challenging the recent news is, how fragile our democracy is feeling, may this be a balm in the form of a recipe for Moroccan Oranges with Cinnamon.

Ingredients: 2 navel oranges, 2 blood oranges

½ cup orange juice, preferably freshly squeezed

2 tablespoon orange blossom water

2 teaspoons sugar and ½ teaspoon ground cinnamon, plus more for a garnish before serving.

Directions: Peel the oranges and remove as much of the pith as possible.

Cut the peeled oranges into ¼ inch slices and add to a mixing bowl.

Add the other ingredients and gently toss the oranges in the mixture. Then cover the bowl and chill in the fridge. This macerates the ingredients for a couple of hours.

Arrange on a dish and sprinkle with cinnamon. Serve with mint tea.

La lotta continua.

Tower Hill Botanical Garden has a special exhibition called “Elevated” that is an orchid show! For the next six weeks, you can find orchids and humans basking in the beauty of the conservatories surrounded by over 2,000 orchids: https://bit.ly/4a5AmEw

Thank you, Hetty. Your piece was just what the doctor ordered as a cure for the cold-weather blues. Orangeries! And closer to home, camellias in Durfee Conservatory! Thanks too, for your recipe for orange marmalade. I will have marmalade on toast tomorrow with my morning tea.