Chapter 70: Some of What You Need to Know to Understand the School Budget Process

Massachusetts Statehouse. Photo: wikipedia

Chapter 70, the primary Massachusetts state aid program for public elementary and secondary schools, is supposedly designed to ensure equitable education funding across all districts. But the formula that allocates these funds can be unintelligible to the average person. When I first heard it casually referenced in a Regional School Committee (RSC) meeting, my brain instantly shut down.

The Amherst and Regional School Committees, the Amherst Town Counciland the Select Boards of the other towns in the region (Leverett, Pelham, and Shutesbury) are now sitting down to plan their budgets for FY 27. Those budgets depend on state aid, or Chapter 70 funding. This state aid accounted for $10,072,811 of the FY26 budget, with $4,169,898 in Foundation Aid (the state’s calculation of adequate funding for a district) and $5,902,918 in Hold Harmless funds (state funding that ensures school districts receive at least the same amount of state aid as in previous years, even if student enrollment declines), according to a Report by the district’s Fiscal Sustainability Subcommittee in September of 2025. It is essential that residents of Amherst and surrounding towns understand how state aid to schools works in order to understand the budget process.

In this column I will not only try to explain the complex workings of Chapter 70 and its intentions, but also to convince you that learning the basics is the first step to advocating for more appropriate public school funding in the state, especially for rural areas like Amherst.

Both the Department of Elementary and Secondary Education (DESE) and the Massachusetts Association of Regional Schools (MARS) have recently addressed the RSC to explain that, despite attempts to arrive at a satisfactory budget, Chapter 70 does not adequately fund rural public schools, due to decreased enrollment and increased special education needs. Both made a clear point that recent school budget crises are not the town’s fault, but due to a problem with the state formula itself.

Understanding this complicated formula for state funding leads to important questions like: why does property evaluation influence local contribution, or what happens when the majority of districts are at the 82.5% budget funding cap? Hopefully, these questions will make more sense and influence your own opinion after reading this piece.

And I apologize in advance for introducing more obscure terminology as I attempt to explain.

Important Terms

Massachusetts General Law Chapter 70, Section 1: The state is required to “assure fair and adequate minimum per student funding for public schools in the commonwealth by defining a foundation budget and a standard of local funding effort applicable to every city and town in the commonwealth.”

Foundation Budget: This is the expected budget for each school district set annually by the state, incorporating the necessary funds to run the buildings and schools, as well as to provide quality education for all students in the state.

Combined Effort Yield: Sets the standard for how much a town can afford to contribute based on the local property valuation multiplied by the uniform property percentage (i.e., the consistent, equitable ratio of assessed value to market value applied to all properties within a taxing jurisdiction) to find the local effort from property wealth reflecting tax income from the town. Then find the local income multiplied by the uniform income percentage (i.e., the percentage based on tax return applied to all towns in the state to create “fair” and “equal” funding) to determine the local effort from income for each town. Add the local effort from property wealth and income to find the combined effort yield.

Required Local Contribution: This is calculated for each town, based on past budgets, and later added up to determine the regional school district budget. To calculate the required local contribution, first compare 82.5% of the foundation budget to the combined effort yield to determine which is less, then figure out how much the town was required to contribute last year, how much the town’s revenue grew this past year, and how close that is to the town’s target contribution.

Hold Harmless: Since school funding is based on enrollment, this standard requires that school districts do not receive less funding than previous years if their enrollment decreases. While funding in the commonwealth is based on enrollment, this standard stems from the original goal of providing fair funding to rural schools and was advocated for by rural districts. There were 211 (out of 360) public school districts in Massachusetts considered to be in hold harmless status in the fiscal year of 2025, according to the Massachusetts Association of Regional Schools.

Minimum Aid: In addition to hold harmless, districts get an additional amount per student each fiscal year. If the district’s enrollment increases, per-pupil funding automatically increases. If schools are losing students, minimum aid guarantees that all schools receive an increase in per-pupil funding across the state. For FY26, the minimum aid per student was increased from $75 to $150, according to DESE.

Proposition 2 ½: In a response to escalating property taxes, this 1980 law caps the amount of the annual tax levy at a 2.5% increase over the previous year plus a factor for new construction and other growth. To raise this tax rate, a town has to vote to override in a townwide election.

Municipal Revenue Growth Factor: How much the town was required to contribute the year before compared to how much the town’s revenue has grown since then. This raises or lowers the local contribution based on the 2.5% levy limit, new growth in the town, state aid, or past payments.

Why is Chapter 70 important?

Right in its constitution, written almost 250 years ago in 1780, Massachusetts dedicated itself to providing appropriate funding to fuel education in the state, which is what Chapter 70 was created to do.

The current funding formula was introduced in the Education Reform Act of 1993 in response to lack of state financial support across the Commonwealth, according to the Massachusetts Budget and Policy Center.

Chapter 70 (as complicated as it is) is supposed to provide all students with a quality education, requires districts to contribute funding according to their ability to raise tax revenue based on local property and income levels, and requires the state to fill in the gap in order to properly fund the foundation budget.

In theory, Chapter 70 (as complicated as it is) is supposed to provide all students with a quality education, requires districts to contribute funding according to their ability to raise tax revenue based on local property and income levels, and requires the state to fill in the gap in order to properly fund the foundation budget.

Explaining Chapter 70

There is an assortment of different factors that influence the foundation budget: the combined effort yield, the required local contribution, and how much districts pay in the end. Ideally, I could touch on every aspect and explain it fully, but that would turn my article into an essay close to the size of a book. For this section, I want to provide a basic understanding of the formula, to improve the general knowledge of how public schools are funded in Massachusetts.

The majority of my explanation is based on a presentation done in 2024 for the Regional School Committee by Tracy Novick, the Massachusetts Association of School Committees Field Director. Here’s the YouTube link and Novik’s presentation for an oral explanation and more specific numbers based on the FY25 budget.

Finding the Foundation Budget

The foundation budget is based on enrollment, meaning the number of students in each grade and their needs. In addition to the standard foundation budget, the state accounts for costs for low-income students, English Language Learners, and special education.

Districts with higher enrollment of low-income students and English Language Learners are provided additional funding based on the percentage of these students. This differs from special education funding, which is based on an assumed percentage of students by the state.

As the state plans the foundation budget, state legislators plan for the statewide foundation budget which falls into the set parameters of 59% local funds and 41% funded by the state based on the Massachusetts Constitution.

Combined Effort Yield

The next step requires the state to calculate the required local contribution, which is based on the taxable property in each municipality and the income in each town to find the combined effort yield. This calculation is based on prior-year records, which inform a town’s ability to pay its share of the budget.

Once a town’s individual property valuation and income are found, they are each multiplied by the uniform percentage determined by the state each year. This equation is used by all towns in the state.

I made this graphic to simplify the equations done by the state and provide a less wordy explanation.

Required Local Contribution

With this information, the next step sets the percentage of contribution for each town. In Massachusetts, no town is required to fund more than 82.5% of their foundation budget, but they are allowed to do so.

The state then compares the combined effort yield sum to the 82.5% cap and bases their next calculations off the lower number.

To find this percentage, the calculation asks for how much the town contributed the year before and how much the town’s tax revenue has grown since then. Comparing these numbers produces the municipal growth factor, as I explained above in the Important Terms section.

Then, the state compares the municipal growth factor to the town’s target contribution to decide how much the town will be required to pay.

Now, add up the required minimum contribution from Amherst, Leverett, Pelham and Shutesbury to find the regional school district’s required contribution to the foundation budget.

Finally, the state can fill the gap with foundation aid, so the foundation budget can be fulfilled.

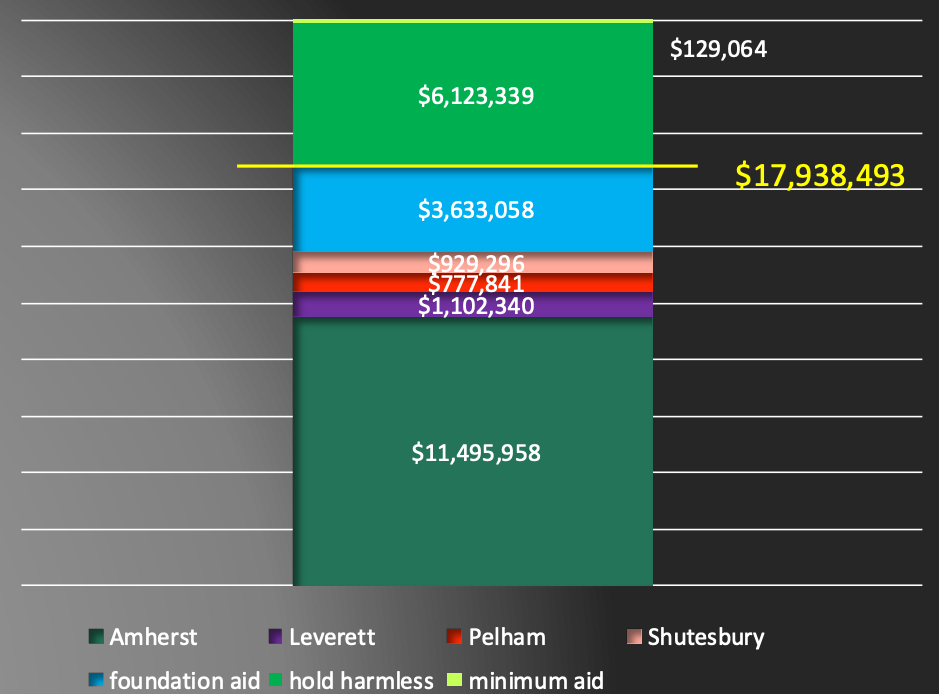

Here’s a chart made by Novik, of the required spending for FY25, when the foundation budget was $17,938,493. This graph does not account for the additional local contribution above the minimum required by the state.

The colors account for Amherst, Leverett, Pelham, Shutesbury, and the foundation aid contributions for the fiscal year, as well as the hold harmless and minimum aid funds, which are also considered required spending.

Hold harmless comes into play because no district can be funded less than the previous year, meaning when a district’s enrollment decreases, their funding does not. Minimum aid accounts for funding per student increasing statewide.

All of this funding is required to be spent during the fiscal year.

Why You Should Know This

Along with other rural school districts in the state, Amherst often does not feel adequately funded by the Chapter 70 formula for a host of reasons. At RSC meetings you’ll hear committee members discussing the high percentage of students in need of special education access, in addition to other needs specific to our district.

When it comes to Chapter 70, since it applies to all towns in the state, there are lots of assumptions about class sizes and regional needs that don’t apply to all regional school districts. Decreasing enrollment is a huge problem for rural areas. In fact, Project 211, introduced by the Massachusetts Association of Regional Schools in 2024, recognizes that 211 school districts receive hold harmless funding, meaning they are facing decreased enrollment. However, decreased enrollment leads to hold harmless funding as the status quo and, as time goes on, to increasingly inadequate funding.

When planning the foundation budget, the state does not consider the number of towns or schools in a regional school district, the central office and school building staff, or declining enrollment. Neither does it include the costs of providing education with fewer students to fund the schools. Regional school districts are also required to provide pre-kindergarden to senior year of high school and to have elementary schools in each membership town, despite the number of students enrolled.

MARS also found that more and more schools are reaching the 82.5% cap for the foundation budget, while the same schools are also suffering from declining enrollment. The association claims that without hold harmless and minimum aid these rural school districts would not exist or would experience drastic cuts.

While legislative action has taken place, there is a lot of work to do considering inflation, special education, transportation, charter school reimbursement, rural school aid and determining minimum aid, according to the Massachusetts Teachers Association.

These are central problems the Amherst Regional Schools and the RSC are facing as we head into the next fiscal year. Understanding the basics is the first step to addressing the more complicated issues that stem from the system. Hopefully by making this information accessible, more and more people can advocate for adequate state funding for rural schools facing declining enrollment.

With the Massachusetts Constitution and Chapter 70 formula recognizing the importance of providing all students with a quality education, the state is already at a great starting point, but we need to be there to hold it accountable.

Read more:

Diverse Coalition, Including MTA, Urges Governor, Lawmakers to Address Public School Funding Crisis (Massachusetts Teachers Association News)

Funding Our Schools (Report on the bill – An Act to Fix the Chapter 70 Inflation Adjustment) (Progressive Mass)