Slavery and Freedom in Northampton, 1654-1783: An Exhibit

September 2025: view at night of the façade of the Parsons House that was used to offer another way of telling the stories of enslaved people featured in the show. Photo: Hetty Startup

Historiography (the study of the writing of history) is a complicated thing, especially as we live in times, to paraphrase Tom Paine, that try our souls. Coming of age as I did in the 1970s, I learned that much of women’s history had been hidden from us, and that “us” was also worth unpacking. A mentor of mine, Sheila Rowbotham, addressed this problem in a book called Hidden From History (1973). Since then, I’ve been learning about similar erasures of narrative, documentation, and evidence, though not a complete erasure of memory and oral history, from both indigenous and African American historians. Indeed, they have been well-served by this kind of history. It is within this historical context that Historic Northampton (a museum that collects and preserves Northampton’s past and engages the community in the exploration of its natural, material, and social history) has launched its latest special exhibition, “Slavery and Freedom in Northampton, 1654–1783.”

The museum was closed for some weeks in January for renovations, but regular hours resume on Wednesday, January 21, 2026 (Wed-Sun 11 a.m. to 4 p.m.), and this fascinating exhibit runs until December 11, 2026. The show actually opened to the public last fall, and there are several opportunities, in addition to visiting it, to learn more about its subject matter in lively and creative ways. For example, there is a special talk about the exhibit scheduled for Sunday, February 1, at 3 p.m.

For at least 129 years, slavery in Northampton had been a part of everyday life as it had been across the river in Amherst. Curator Elizabeth Sharpe and an expert exhibit team (that included Mike Hanke and Design Division, Inc.) have succeeded in bringing some aspects of the lives of at least 50 enslaved individuals to life, vividly demonstrating that they were a part of the town from its settlement by the English in 1654 until 1783, when slavery was officially abolished in Massachusetts. This part of the country was known as a hotbed of abolitionism, and it is worth remembering that folks all over New England continued to agitate for an end to slavery everywhere; New York state abolished slavery much later, in 1827.

One focus of this exhibit demonstrates how some individuals won their freedom here while also noting that almost all of them raised families of their own. We see evidence of this in the exhibit in several ways that I will discuss shortly. The show also indicates that other enslaved people, like their contemporaries in Amherst, went on to own property. Larger towns like Amherst and Northampton were not the only places where this happened; smaller towns in western Massachusetts such as Ashfield, included Heber Honestman, a freed slave from the town of Easton who came to Ashfield, then called Huntstown, in the early 1740s, and who went on to own property as one of the original town proprietors.

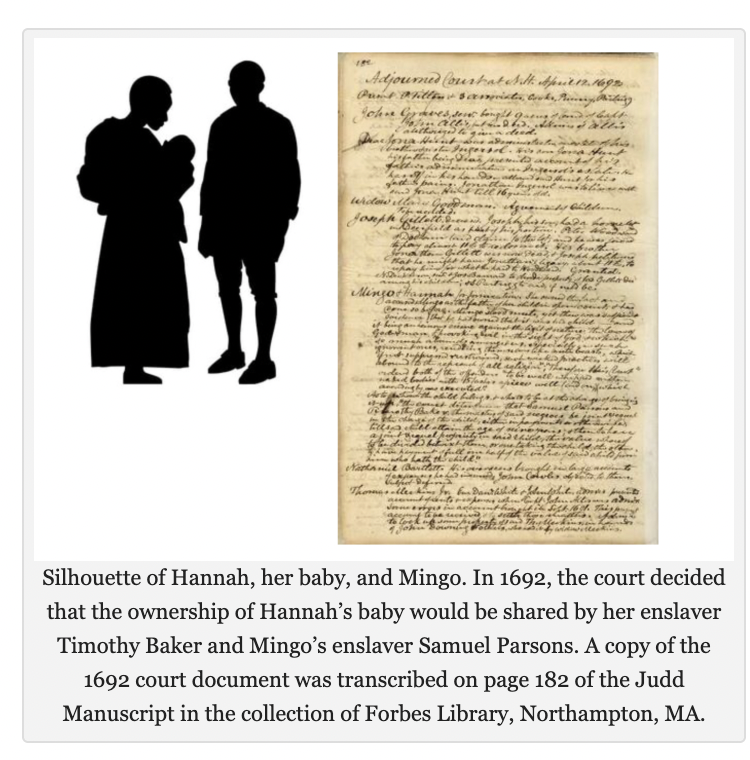

This development happened earlier in larger, more urban towns like Northampton. For example, in 1692, as we learn in the exhibit, the Massachusetts State court ruled in the case of a woman named Hannah, her baby, and the baby’s father, a man named Mingo, determining that ownership of the baby would be shared by her enslaver, Timothy Baker, and Mingo’s enslaver, Samuel Parsons. The Parsons family connection is important because one of the properties that makes up the group of buildings that is Historic Northampton is the Parsons House, still on its original 1654 homelot, that dates, as a structure, from 1719). This is a rare colonial home located next to the organization’s offices and exhibit space.

I mentioned at the beginning of this review that the exhibit can be experienced in a variety of ways. Last fall, the exhibit team used the front facade of the Parsons house at night as a screen for the display of images of the people who are featured in the exhibit (see above).

It may be obvious to readers of the Indy that this exhibit makes the enslaved people the very center of the story as much as, if not more than, their enslavers or their white owners. Decades ago this most likely would not have been the case either in schools or in many museums. One doesn’t have to go too far back in time – decades really – to remember that the dominant narrative in the North of the United States was that there were clear winners and losers and that the North was superior (or more enlightened) even though slavery existed here too! White abolitionists got a lot more agency and ‘play’ than enslaved individuals when I was at college and studying this topic more deeply.

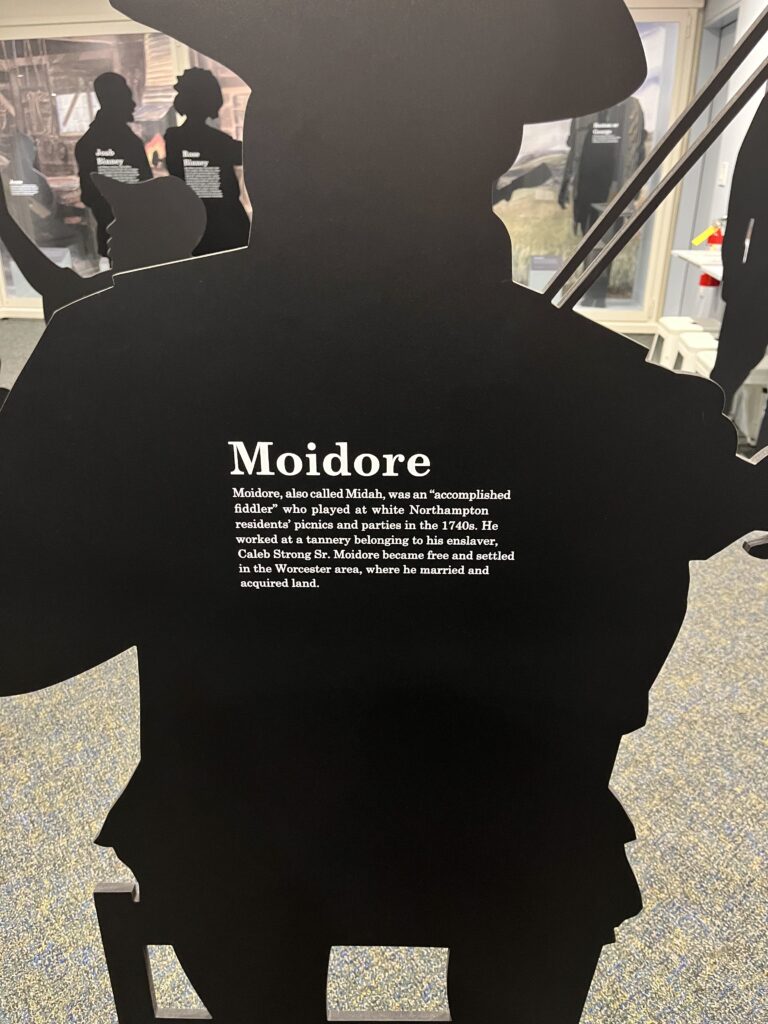

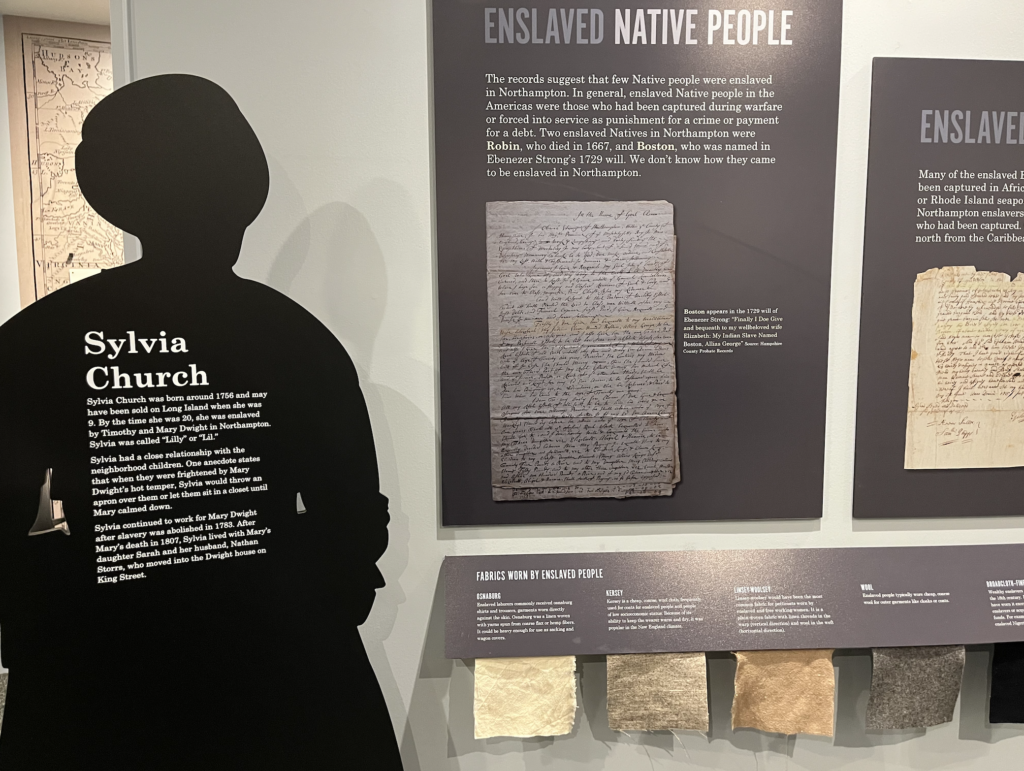

In this exhibit we can see how owning slaves could help whites to accumulate wealth or capital. This is why there are discussions around the unequal experiences of blacks and whites in building equity over time- and why reparations is an important issue. In Northampton, as elsewhere in British North America and the young Republic, owners of enslaved people had connections – through family, though trade and through commerce – to European slavers. But what is overwhelming in this exhibition is the presence (in silhouettes) of the completely different world of enslaved people, all named, and it is possible to move through the show with them taking center stage. We learn about how they worked without pay or rights in the houses and homes of well-to-do people in Northampton.

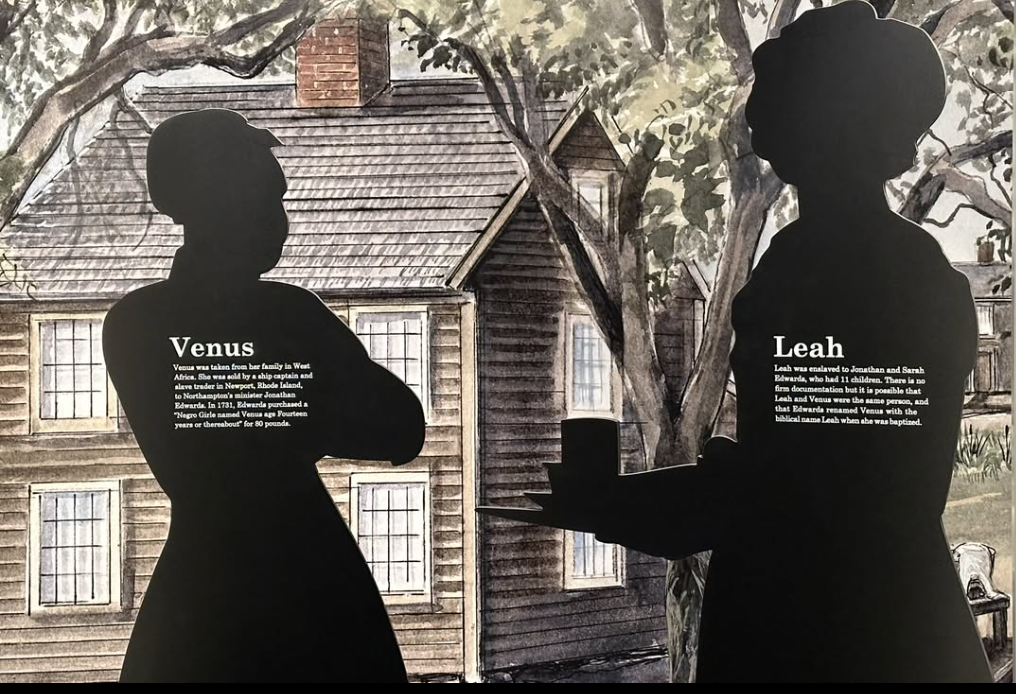

One person was a woman named Venus who was taken from her family in West Africa.

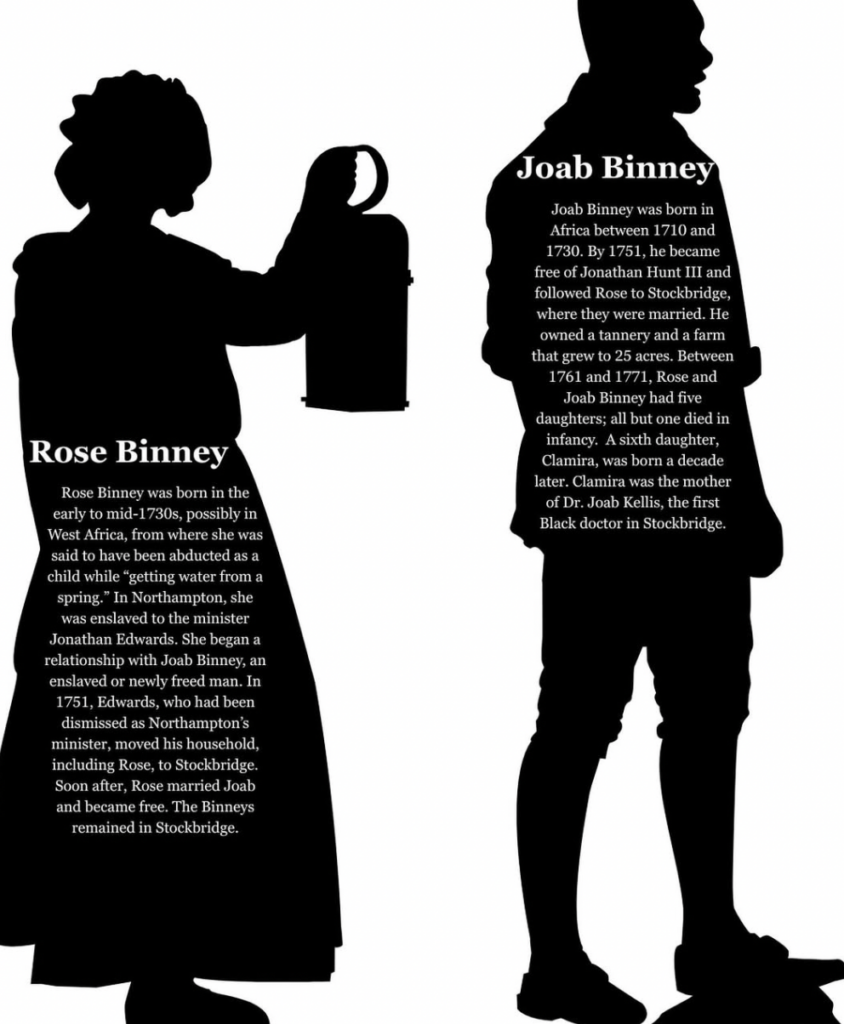

Venus was sold by a ship’s captain and slave trader in Newport, Rhode Island to Northampton’s minister Jonathan Edwards. The documents reveal that in 1731, Edwards purchased a “Negro Girle named Venus age Fourteen years or thereabout” for 80 pounds. Similarly, we meet Rose Binney, born in the early to mid-1730s, possibly in West Africa, from where she was said to have been abducted as a child while “getting water from a spring.” In Northampton, like Venus, she was also enslaved to the minister Jonathan Edwards. There she began a relationship with Joab Binney, an enslaved man who later became free. In 1751, Edwards, who had been dismissed as Northampton’s minister, moved his household, including Rose, to Stockbridge, MA. Soon afterwards, Rose married Joab and became free herself. The Binneys were to remain in Stockbridge for the rest of their lives.

Perhaps because he was a man, there is more that is known at present about Joab Binney, who was born in Africa (the country is not specified in the documentation) between 1710 and 1730. By 1751, he had become free of Jonathan Hunt III and followed Rose to Stockbridge, where they were married. Joab owned a tannery and a farm that grew over time to 25 acres. Between 1761 and 1771, Rose and Joab Binney had five daughters; all but one died in infancy. A sixth daughter, Clamira, was born a decade later. Clamira was the mother of Dr. Joab Kellis, the first Black doctor in Stockbridge.

As I see it, one of the real benefits of the show is that anyone from our communities visiting the exhibit can see portraits of people like themselves. This has been part of a trend that can be seen in many regional galleries and museums. This more inclusive, multicultural narrative is being questioned by the Trump administration, which has taken an aggressive stand against narratives that present many and diverse stories that challenge the notion of one master narrative or that do not present an idealized picture of the United States as a nation that can do no wrong.

At Historic Northampton, the exhibit’s designers have chosen to tell the story of early Northampton residents through silhouettes of men, women, and children who were enslaved in Northampton. These silhouettes are slightly larger than life-sized and do several things. They immediately act to put you in a relationship with the people who are named and also offer another way to learn about each person alongside written documents (that were biased against enslaved people).

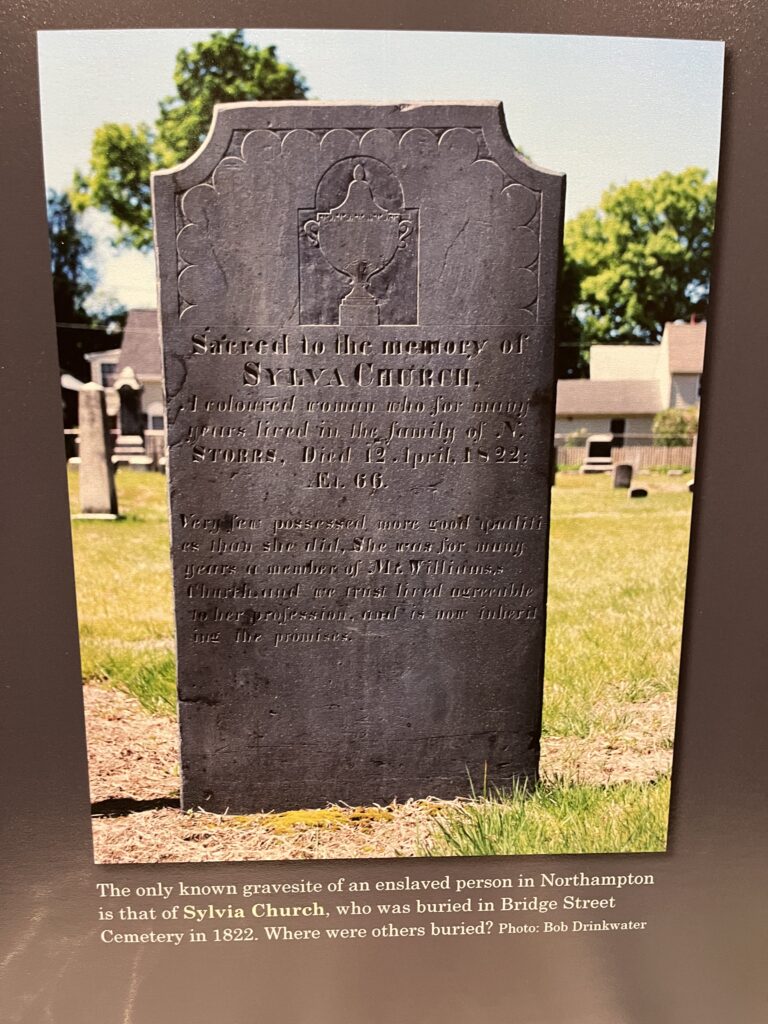

We also learn that Sylvia Church, one of the people mentioned in this exhibit, is buried in Bridge Street Cemetery.

Yet another portal into the exhibit was a day-long program where anyone could come in to see archival documents related to slavery in Northampton with the museum educator Elizabeth Sacktor, Forbes Library’s archivist Dylan Gaffney, and Registrar of Probate Mark Ames. This free program offered closer study and discussion of the material evidence and legacies of slavery in our community. I hope it is possible for this to happen again sometime this year along with another night offering digital projection of people I now know a little bit more about thanks to this exhibit.

The current show adds to the names and stories of better-known African-American men and women like David Ruggles and Sojourner Truth, who lived in Northampton in the early 1800s. They were a part of a group of abolitionists who formed and/or joined the Northampton Association of Education and Industry, a utopian community created in the 1840s in what is now the Northampton neighborhood of Florence. Members of this association – for a short time – created a life that embodied the principles of racial, gender, and economic equality. Their story is told at the David Ruggles Center in Florence.

But even after slavery was abolished in Massachusetts and neighboring New York State, the dangers to Black people – enslaved or free – did not end.

My interest in reviewing the show was, in part, to compare Amherst’s and Northampton’s early histories, both of enslavement and of documented attempts to secure freedom. It would be amazing to see a show like the one in Northampton in Amherst at some point in the future. We know that African Americans, both enslaved and free, had been resident in Amherst since the 18th century, although exactly where they lived is not always clear. An enslaved child named Wealthy Wheeler, a 5-year-old girl who had been purchased by Oliver Cowls in 1790, went on to live with the family household until 1850 in a North Amherst neighborhood that had declared an early anti-slavery stance compared to the town as a whole. From the 1820 census, it can be seen that some African Americans in Amherst maintained their own households: Samuel Bakeman, Zacheus Finnemore, William Jackson, and Jeptha Pharoah. And we have come to find out – thanks to the genealogical work and activism of people like local businesswoman and former Town Councilor Anika Lopes – and her foundation, Ancestral Bridges – that one Amherst neighborhood in particular (Hazel, Snell, and Baker Streets) is our oldest known black neighborhood, dating from the 1860s. It has stayed this way pretty much to the present day in part due to the lively proximity of the town’s two African-American churches. Hazel Avenue is close to Amherst College, an important employer of Black residents throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Yet another small enclave of Amherst’s black population was located in a tenement on North Pleasant Street that was known as the “Bee Hive,” not far from the home of Emily Dickinson’s youth from 1840-1855. This is the area where Panda East and Boltwood Walk are now.

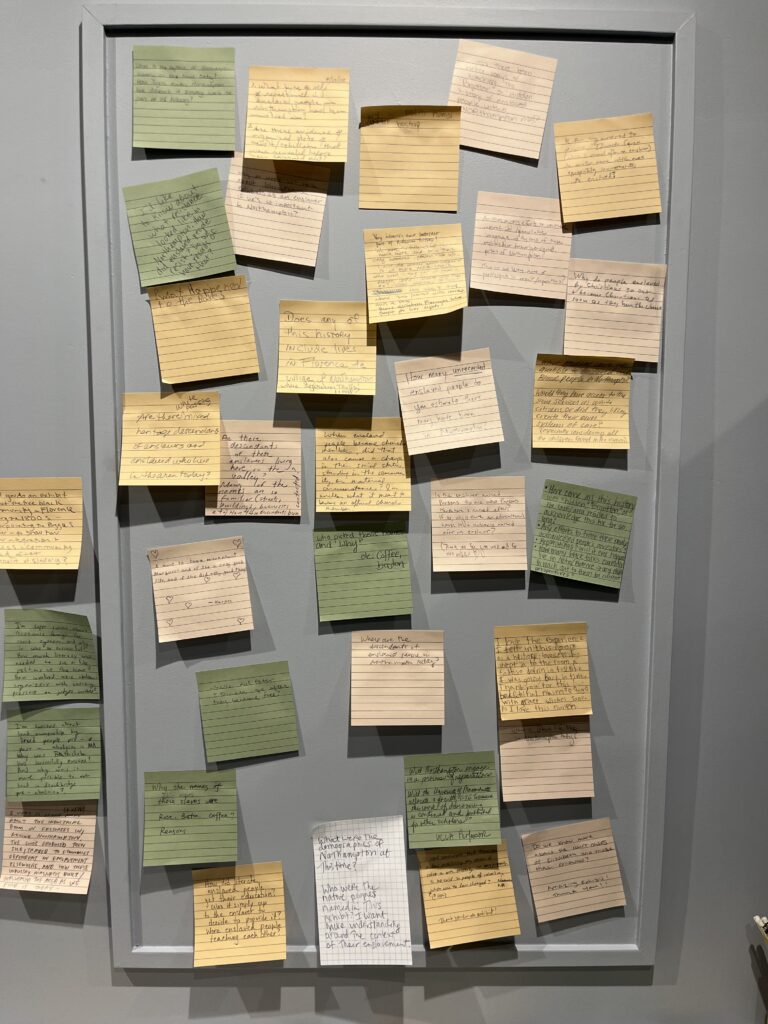

Clearly, there is ample opportunity to learn more. The documents exist and so does the expertise. A counterpart to the Northampton exhibit would be a wonderful addition to our town histories. At the Historic Northampton show, there is a talk-back board that also suggests more to come.

The Talk-Back board in the exhibit. Photo: Hetty Startup