Almanac

River otter. Photo: wikimedia commons

Editor’s Note: This is the inaugural post in what will be a regular Indy column of observations, musings, and occasional harangues related to the woods, waters, mountains, and skies of the Pioneer Valley.

Otter

On a hike to the Quabbin Reservoir’s west arm the other week, I saw an otter gallumphing across the ice, heading toward open water. I said something to my companion and the otter stopped and looked at us. We stood still. It stood still. Then it turned, took another dozen hopping leaps to the ice’s edge, and slid smoothly into the water.

I wish I could have watched it from there. In videos, otters are amazingly graceful, acrobatic, and wholly at home in that element. They’re like loons that way…rather clumsy and awkward on land, but astonishingly agile underwater. We weren’t close enough to see details of the otter’s face, and, as usual, I didn’t have time to pull out the binocs at the bottom of my pack. But otters have cute seal-like heads and a long, thick tail that tapers to a point. They are, essentially, big weasels that have adapted to the water with four webbed feet, eyes set high in their heads for seeing while paddling on the surface of the water, and thick, oily fur that keeps them comfy in the coldest weather.

They can swim about a half-mile underwater and hold their breath for up to four minutes. River otters (also known as land otters, or common otters) are undoubtedly the fastest swimmers among North American land mammals, capable of outswimming such game fish as trout and salmon. Otters will eat these fish when they can, but usually prefer slower quarry such as carp, perch, suckers, crayfish, frogs, salamanders, snails, and insect larvae.

Otters have few natural enemies, save humans, and are known for their energy and playful dispositions. One book on mammals aptly calls otters “good natured dynamite.” If I had more time I would have looked for a slick icy chute on the shore near where I saw it. Such chutes are commonly built by otters and have only one function: fun. Otters will slide down their chutes for hours on end until hunger drives them back to the task of hunting. In summer, they create mud slides for the same entertainment. Few other New England animals go to such lengths to amuse themselves, although many other animals in the world have been observed behaving in ways that I’m perfectly happy to interpret as “play” even though we can’t interrogate them and ask what they’re up to.

The sight of otters is always heartening because their numbers have been drastically reduced by trapping and habitat destruction. Otters have been known to co-exist with humans in certain areas, but they far prefer unpolluted wilderness waters. The Quabbin, being a water supply for Boston, is certainly clean, and its waters are relatively undisturbed by humans, with the exception of fishing boats, which are allowed even though private non-motorized boats such as canoes and kayaks are prohibited. As an avid kayaker, this happens to be a sore spot for me, but I’ll pick that particular bone some other time.

Now You See ‘Em, Now You Don’t

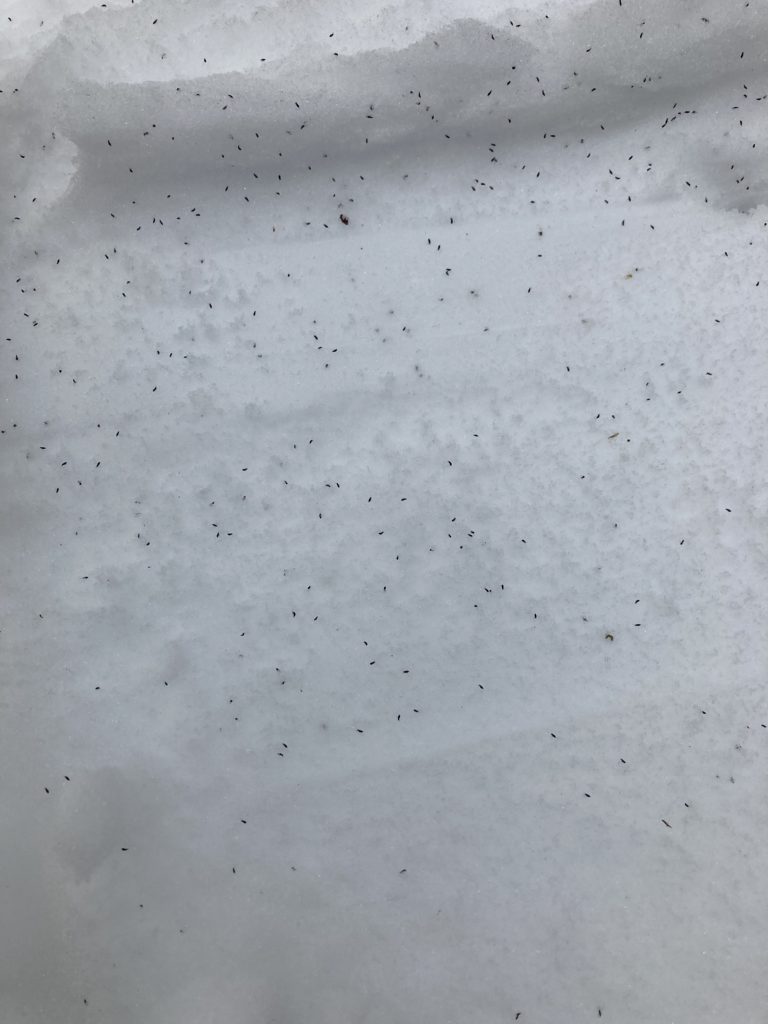

While cross country skiing the forested trails of Northfield Mountain this past weekend, I noticed that the snow in places was covered with minute dark specks, like a dusting of pepper. I bent down to take a close look. Suddenly the speck at which I was peering vanished as if into thin air. Hmmmm… I looked at another speck. This one stayed put long enough for me to make out some tiny legs along a tiny oval body no larger than the period at the end of this sentence. Then this dot disappeared as well.

I was looking at a type of wingless insect called a springtail, specifically a species with the appropriate common name of snow flea. Snow fleas, like the other 314 varieties of springtails in North America, are scavengers. With their tiny mouths they consume decaying plant matter and serve, in turn, as food for larger insects.

Springtails get their name from a tiny forked appendage called a furcula, which is attached to the underside of their bodies near their tail. The furcula is normally curled forward under the body, but it can be snapped back at will, like a leaf spring, propelling the insect into the air. This is not a terribly accurate mode of transportation since the insect simply catapults itself with very little control over its direction. But given the huge numbers of springtails in the world, it must suffice well enough to ensure survival.

The snow fleas I saw were probably scavenging pollen and algal cells from the snow. It was a relatively mild day, but, still, below freezing. Given that insects are cold-blooded, why don’t springtails freeze solid on the snow? Two things probably protect them. First of all, their bodies are very dark — almost black — enabling them to absorb enough solar radiation to keep them warmer than the snow. Secondly, springtail blood probably contains anti-freezing chemicals such as the alcohols sorbitol and glycerol, and/or proteins rich in the amino acid glycine.

Stephen Braun has a background in natural resources conservation, which mostly means he is continually baffled by what he sees on explorations of local natural areas. Please feel free to comment on posts and add your own experiences or observations. You can also email at: braun.writer@gmail.com.

Great new feature – thanks to SB for doing these!

I am so glad to have this as a feature in the Indy. I appreciate the keenness of Steve’s observations and his writing.

P.S. As a canoeist, I too am disappointed that the Quabbin is off limits to human-powered boats — maybe it’s time to look into that, Steve — are you game?

Re: Human-powered boats. Forty years ago I was told by a former Army Corp of Engineers employee that Quabbin personnel didn’t want to have to tow becalmed or disabled sailboats to shore.