A Better World Is Possible: The Circular Economy

Linear vs circular economy. Wikimedia Commons

This week’s Indy features an op-ed by Darcy DuMont, highlighting the benefits of a circular economy and offering suggestions for how the idea might be implemented in Amherst to help the town achieve its climate action goals.

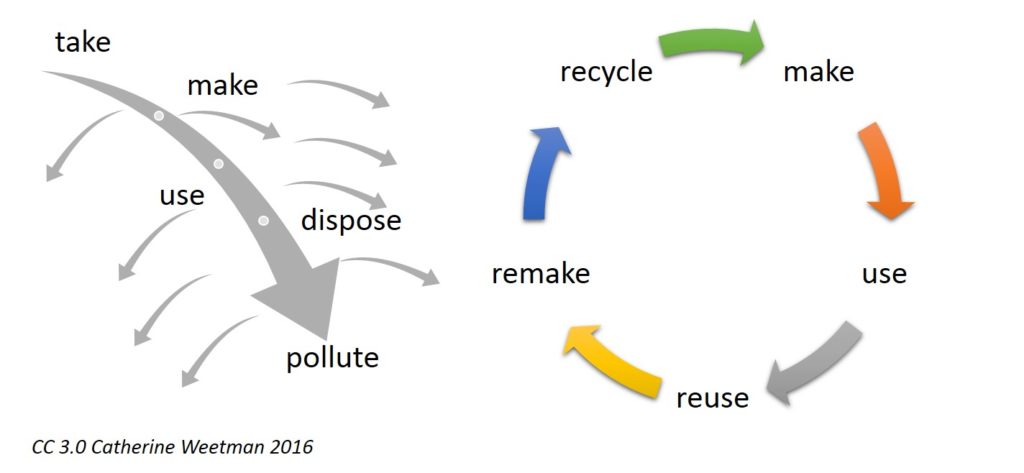

According to the Ellen McArthur Foundation, a prominent advocate for the circular economy, saving the planet requires the following shift. “In our current economy, we take materials from the Earth, make products from them, and eventually throw them away as waste – the process is linear. In a circular economy, by contrast, we stop waste being produced in the first place. The circular economy is based on three principles driven by design: eliminate waste and pollution, circulate products and materials (at their highest value), and regenerate nature. It is underpinned by a transition to renewable energy and materials. A circular economy decouples economic activity from the consumption of finite resources. It is a resilient system that is good for business, people and the environment.”

The discussion of circularity and the dead-end that a linear economy produces reminds me of a warning Noam Chomsky made three decades ago.

It remains to be seen whether the circular economy offers an antidote to Chomsky’s grim diagnosis or merely provides cover for the industrial practices and policies and the capitalist logic at fault for making the earth uninhabitable. Those promoting the circular economy have suggested that it offers a path for saving capitalism (sometimes referring to it as sustainable or natural capitalism) or a pathway away from capitalism toward a sustainable economy. Obviously it can’t be both. But one thing is clear: those talking about a circular economy are engaged in a discourse about moving our daily practices, our economies, our societies, toward sustainability and away from unfettered consumption and waste. Can these initiatives have a substantial impact or do they fail to address the core of what ails us?

This week’s A Better World Is Possible offers links to sources that tell the story of the circular economy. I recommend that if you read just one piece, it be Lisa Abend and Ingmar Bjorn Nolting’s article in Time Magazine about Finland’s efforts to eliminate waste by 2050. And for a more comprehensive introduction to the circular economy, I recommend the web pages of the Ellen MacArthur Foundation. In addition to those introductory pieces, I offer links to some case studies and to some critiques of the concept and its implementation.

Readings On The Circular Economy

General Introductions

Inside Finland’s Plan To End All Waste By 2050 by Lisa Abend and Ingmar Bjorn Nolting (1/20/22). Finland stands out for the comprehensiveness of its approach. Back in 2016, it became the first to adopt a national “road map” to a circular economy—a commitment it reaffirmed last year by setting targeted caps on natural-resource extraction. Like other nations, Finland supports entrepreneurship in creative reuse, or upcycling (especially in its important forestry industry), urges public procurements that rely on recycled and repurposed materials, and seeks to curb dramatically the amount of waste going to landfill. But from the beginning, the country of 5.5 million has also focused closely on education, training its younger generations to think of the economy differently than their parents and grandparents do. “People think it’s just about recycling,” says Nani Pajunen, a sustainability expert at Sitra, the public innovation fund that has spearheaded Finland’s circular conversion. “But really, it’s about rethinking everything—products, material development, how we consume.” To make changes at every level of society, Pajunen argues, education is key—getting every Finn to understand the need for a circular economy, and how they can be part of it. (Time)

What Is The Circular Economy? by The Ellen MacArthur Foundation (no date). In our current economy, we take materials from the Earth, make products from them, and eventually throw them away as waste – the process is linear. In a circular economy, by contrast, we stop waste being produced in the first place. The circular economy is based on three principles, driven by design: eliminate waste and pollution, circulate products and materials (at their highest value) and regenerate nature. It is underpinned by a transition to renewable energy and materials. A circular economy decouples economic activity from the consumption of finite resources. It is a resilient system that is good for business, people and the environment. (Ellen MacArthur Foundation Website)

The Seven Pillars Of The Circular Economy by Eva Gladek (8/15/2019). As we continue to explore the implications of striving for a fully closed, circular material cycle as a cornerstone of the economy, we ultimately encounter many other connections throughout the economic system that need to be arranged in a way which upholds broader human ideals. In the end, this exercise resulted in a set of seven characteristics which describe the end state of the circular economy once it has been genuinely achieved. These are idealized features that may never be possible to achieve, but they provide a specific set of targets we can aim for. Furthermore, each one can be characterized in greater, quantitative detail, forming the basis for Circularity Indicators, or KPIs, in many different contexts. (Metabolic Website)

Case Studies

Amsterdam Is Embracing A New Radical Economic Theory To Help Save The Environment. Could It Also Replace Capitalism? by Ciara Nugent (1/22/21). In April 2020, during the first wave of COVID-19, Amsterdam’s city government announced it would recover from the crisis, and avoid future ones, by embracing the theory of “doughnut economics.” Laid out by British economist Kate Raworth in a 2017 book, the theory argues that 20th century economic thinking is not equipped to deal with the 21st century reality of a planet teetering on the edge of climate breakdown. Instead of equating a growing GDP with a successful society, our goal should be to fit all of human life into what Raworth calls the “sweet spot” between the “social foundation,” where everyone has what they need to live a good life, and the “environmental ceiling.” By and large, people in rich countries are living above the environmental ceiling. Those in poorer countries often fall below the social foundation. The space in between: that’s the doughnut. (Time)

New Zealand’s Government Plans To Swtich To A Circular Economy To Cut Waste And Emissions by Hannah Blumhardt (11/3/21). The New Zealand government is currently developing plans to address two crises—climate change and waste—and to embrace a circular economy. But it has no clear path for how to do this. The resulting muddle is watering down the potential of a circular economy to bring lasting change. Public consultation is underway to develop an emissions reduction plan, following the Climate Change Commission’s advice on carbon budgets towards New Zealand’s 2050 net-zero target. Another consultation document proposes to overhaul the country’s waste strategy and legislation. Both documents intend to move Aotearoa towards a circular economy—one that limits waste and pollution, keeps products in use, and regenerates natural systems to protect, not pillage, natural resources. But the government’s plans for circularity are fragmented, contradictory and uncoordinated. They fail to confront the business-as-usual drivers of the linear economy or to enhance collaboration. (Phys.org)

Six Circular Economy Case Studies In The USA by Nick Jeffries (9/11/17). Circular design thinking has been demonstrated very elegantly by Mohawk-Niaga, which has created a new 100% recyclable carpet material, that can be used for both the backing and surface layers. It has been estimated that carpets account for 3.5% of all material disposed of in US landfills, amounting to 2 million tonnes of lost materials each year. Mohawk-Niaga’s new material could help close the loop in carpet manufacturing so that materials can be diverted from landfill and instead be continually recycled. (Medium)

Municipality Led Circular Economy Case Studies by The C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group (no date). An increasing number of municipalities have an ambitious vision and strategy to become minimal or zero waste cities in the near future. Embedding circular economy principles into urban operations helps cities to minimise waste by moving beyond the traditional linear economy – closing the loop with a holistic and regenerative approach to design, production, consumption and disposal. Cities are seeking answers to the critical questions about what hurdles need to be overcome on a municipality level, how business and civil society can be engaged, and what the key benefits of incorporating circular economy principles are for stakeholders. This publication presents the experience of 40 municipalities which have embedded circular economy principles into their systems and value chains, and is organised around five areas where cities have significant potential to do so. For instance, cities are initiating living laboratories to test new concepts in regeneration districts, and renting rather than purchasing goods through public procurement to save money and encourage new business models. Download the 40 case studies here.

(C40 Cities)

Critiques

Will The Circular Economy Save The Planet? by Elizabeth L. Cline (12/23/20). Over the past decade, the idea of shifting the economy away from a linear model to a circular one to solve our environmental woes has taken hold in corporate boardrooms and government offices around the world. Last June, leaders from the World Economic Forum, the European Parliament, Fortune 500 companies, and environmental groups endorsed the circular economy as a way to restore the environment and promote growth in response to the coronavirus pandemic. Google, Amazon, Coca-Cola, IKEA, Unilever, and H&M have all rolled out ambitious plans to go circular. The United Nations identifies circularity as a key pillar of its Sustainable Development Goals. While a global plan to become more sustainable sounds like progress, the circular economy is a huge and fuzzy concept, and it can be hard to pin down how exactly it translates into practice. A 2017 research paper on the topic identified at least 114 definitions of the term, with the majority amounting to little more than reuse and recycling. This is concerning because environmentalists have been championing reuse and recycling for decades, but our exploitation of resources has only intensified. Like other utopian environmental theories before it, the circular economy promises to decouple economic growth from our endless consumption of stuff, but are its proponents really offering a planet-saving paradigm shift, or just another version of something we’ve tried and failed at for decades? (Sierra Magazine)

Critiques Of The Circular Economy by Hervé Corvellec,Alison F. Stowell,Nils Johansson (8/17/21). This paper presents a reasoned account of the critiques addressed to the circular economy and circular business models. These critiques claim that the circular economy has diffused limits, unclear theoretical grounds, and that its implementation faces structural obstacles. Circular economy is based on an ideological agenda dominated by technical and economic accounts, which brings uncertain contributions to sustainability and depoliticizes sustainable growth. Bringing together these critiques demonstrates that the circular economy is far from being as promising as its advocates claim it to be. Circularity emerges instead as a theoretically, practically, and ideologically questionable notion. The paper concludes by proposing critical issues that need to be addressed if the circular economy and its business models are to open routes for more sustainable economic development. (Journal of Industrial Ecology)

Treating The Symptom: A Marxist Reflection On Zero Waste by Marc Kalina (3/5/20). The purpose of this letter is to draw attebtion to a perceived failure within waste management studies to adequately engage with the socio-economic and socio-political conditions that drive the production of waste. By way of a solution, it proposes a return to Marxist dialectics and modes of analysis in order to reframe contemporary debates on waste management practices to include more critical discussion and engagement with the root causes of waste, specifically capitalist production and class- addressing the illness rather than merely treating the symptoms. (Detritus)

3 thoughts on “A Better World Is Possible: The Circular Economy”