A Better World Is Possible: Bhutan’s Gross National Happiness

View of the highest peak in Bhutan, Kangkar Punsum, At 24, 836 feet, it is the highest unclimbed mountain in the world. Bhutan has designated many of their peaks as sacred and off limits to climbers, forgoing the prospects for commercial tourist development. Photo: Art Keene

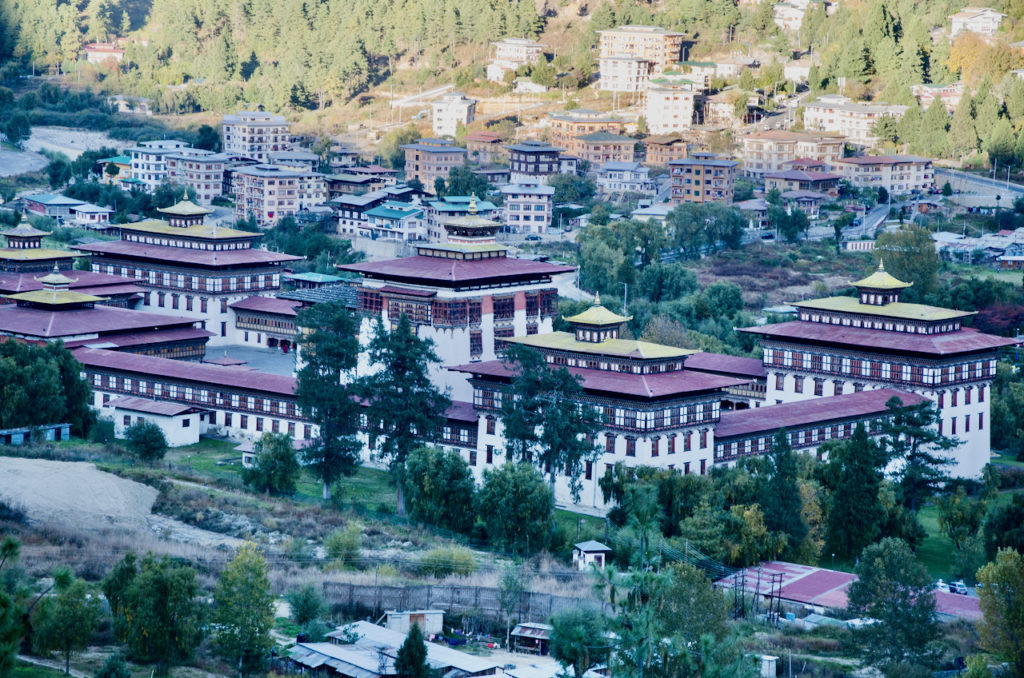

In 2016 my wife and I spent a couple of weeks hiking in Bhutan. Bhutan is a stunningly beautiful country and especially interesting for the perspective it offers on so many of the challenges that we face here at home. A small nation of 800,000 people precariously positioned between China and India in the Eastern Himalayas, Bhutan consists primarily of forest and agricultural land with little urban development. It is 15 years into a bold experiment in democracy, having moved in 2007 from a monarchy to a constitutional monarchy with most political power vested in a democratically elected parliament. The people of Bhutan embraced democracy warily at the urging of their king and with few having any previous experience with the practice. Bhutan is a world leader in trying to foster a commitment to a sustainable economy. Bhutan was the first carbon negative country in the world. This means that it removes more carbon from the atmosphere than it emits into it. Bhutan was joined by Suriname in 2022 as the only other carbon negative country in the world. While a poor, developing country, Bhutan nonetheless provides universal free education and universal free health care to its people. Its constitution specifies that 60% of the nation’s land must be permanently set aside as a nature reserve. And it is most widely known for the concept of Gross National Happiness (GNH), which measures the nation’s success and sets all development goals in terms of the well-being of all of the people, rather than in terms of material production, which, in its current global manifestation, is exhausting the planet’s capacity to sustain life. And so we visitors were told stories of development projects that had been recently rejected because they were not sustainable or because they did not explicitly contribute to collective wellbeing.

Now, as the Bhutanese will readily tell you, the place is not utopia. It has had all kinds of growing pains and missteps, including the harsh treatment of the country’s Nepali minority. And the country is still quite poor (see this article from NPR for a discussion of challenges the country faces in living up to its “happiness for all brand”). But the concept of shaping national policy around sustainability and universal wellbeing is intriguing and inspiring, sufficiently so, that it has been taken up elsewhere around the globe (see below). To paraphrase our Buddhist hosts, the place is pregnant with possibility — the possibility of organizing a society around very different principles than those governing the rest of the globe. Indeed, just about everyone we met on our brief trip exhibited that tendency of dwelling in possibility and in the daily practice of trying to envision what is possible and what might be done for the benefit of all and of growing the nation within the requirements of sustainability.

How GNH Works (sources: Wikipedia and NPR)

Julie McCarthy of NPR notes: “Divining gross national happiness is a matter of minutely categorizing and carefully tracking the lives of Bhutan’s 800,000 citizens. Every five years under the direction of the Centre for Bhutan Studies and GNH Research, survey-takers fan out across the country to conduct questionnaires of some 8,000 randomly selected households. The survey is broken down into nine “domains,” 33 “indicators,” and hundreds more variables. The broad categories include psychological well-being, health, time use, education, culture, good governance, community vitality, ecology, and living standards.”

The first Bhutanese GNH survey was conducted in 2008. The body charged with implementing GNH in Bhutan is the Gross National Happiness Commission. The Commission uses the index to measure national progress and inform policy. The Bhutan GNH Index is considered to measure societal progress similar to other models, such as the OECD Better Life Index of 2011, and SPI Social Progress Index of 2013. The data are used to compare happiness among different groups of citizens, and changes over time.

The holistic consideration of multiple factors through the GNH approach has been cited as impacting Bhutan’s successful response to the COVID-19 pandemic (see also here).

The Idea Of GNH Beyond Bhutan (source: Wikipedia)

In Victoria, British Columbia, Canada, a shortened version of Bhutan’s GNH survey was used by the local government, local foundations, and governmental agencies to assess its population.

In the state of São Paulo, Brazil, Susan Andrews, through her organization “Future Vision Ecological Park,” used a version of Bhutan’s GNH at a community level in some cities.

In Seattle, Washington, a version of the GNH Index was used by the Seattle City Council and Sustainable Seattle to assess the happiness and well-being of the Seattle area population. Other cities and areas in North America, including Eau Claire, Wisconsin; Creston, British Columbia; and the U.S. state of Vermont, also used a version of the GNH Index.

The state of Vermont declared April 13 (President Thomas Jefferson’s birthday) “Pursuit of Happiness Day,” and became the first state to pass legislation enabling the development of alternative indicators (to things like GDP) to assist in making policy. The University of Vermont Center for Rural Studies (Vermont) performs a periodic study of well-being in the state.

At the University of Oregon, a behavioral model of GNH based on the use of positive and negative words in social network status updates was developed by Adam Kramer.

In 2016, Thailand launched its own GNH center. The former king of Thailand, Bhumibol Adulyadej, was a close friend of Bhutan’s King Jigme Singye Wangchuck, and conceived the similar philosophy of Sufficiency Economy.

In the Philippines, the concept of GNH has been lauded by various personalities, notably Philippine senator and UN Global Champion for Resilience Loren Legarda, and former environment minister Gina Lopez. Bills have been filed in the Philippine Senate and House of Representatives in support of Gross National Happiness in the Philippines.

Many other cities and governments have undertaken efforts to measure happiness and well-being (also termed “Beyond GDP”) but have not used versions of Bhutan’s GNH index. Among these are the United Kingdom‘s Office of National Statistics, the United Arab Emirates, and cities including Somerville, Massachusetts, and Bristol, United Kingdom.

Also a number of companies are implementing sustainability practices in business that have been inspired by GNH.

Additional Resources

Measure What Matters – Indicators of Gross National Happiness. By Gross National Happiness USA

What Bhutan Got Right About Gross National Happiness

National Progress, Sustainability And Higher Goals: The Case Of Bhutan’s Gross National Happiness

A Better World Is Possible is a mostly weekly Indy feature that offers snapshots of creative undertakings, community experiments, innovative municipal projects, and excursions of the imagination that suggest possible interventions for the sundry challenges we face in our communities and as a species. The feature complements our regular column by Boone Shear, Becoming Human. Have you seen creative approaches to community problems or examples of things that other communities do to make life better for their residents that you think we should be talking about? Send your observations/suggestions to amherstindy@gmail.com. See previous posts here.