Amherst History Month-by-Month: Native Lands Connected By Water

Amherst College china used from the late 1920s, again during World War II (from 1941 onwards) and until 1973 when the Syracuse china was discontinued. Photo courtesy of Anika Lopes and Ancestral Bridges.

“Grant that before I judge my neighbor I walk in [their] Moccasins for many moons.

Native American Proverb

In one of the Valley’s hilltowns last weekend, I listened with many other people to Nipmuc author and storyteller Larry Spotted Crow Mann read his poetry. He is always inspiring. The program was a moment when I wondered how Amherst’s Native histories might be amplified as we are currently honoring National Native American Heritage Month. But that’s not the only reason these kinds of narratives need to be better known. There are over five million Native people in this country and 574 Native nations that have nation-to-nation relationships with the U.S. government.

But writing about Native history is complicated not only because so much of it is traumatic in nature but also because of whose voices and meanings have most commonly prevailed until recently. As a white commentator, can I really speak on behalf of people underrepresented in dominant histories of Amherst? Doing so seems like a double whammy. I’m going to go ‘where angels fear to tread’ because I am learning that so much about this column is dedicated to remembering and appreciating where we live and valuing all its historic buildings, landscapes, and diverse peoples – its collective histories, if you like – hoping to do better now and into the future.

Indigenous peoples here, despite deep prejudice and racism over time, have built community, preserved their lives and languages, their sacred sites and also protected foodways and art making, kinship systems and a deep, abiding earth wisdom. I will talk more about that last quality in a minute because it runs counter to most prevailing (white) ideas of land conservation and historic preservation. Authors like Montague resident David Brule, the president of the local Nolumbeka Project, and member of the Nehantic Tribal Council, has shared this history for many years, especially for Valley residents. I vividly remember his tour of the pine barrens of Montague several years ago when he shared the history of this sacred landscape of sandplains and explained how paleo-ecological evidence shows that native peoples used fire on the Montague Plains from 500 years ago to at least 2,000 years before European settlement. It was used as a land management strategy to increase mast (nuts and grains and seeds) for hunting game and to assist in travel through the region.

With some temerity, I’ve picked two important native sites in Amherst and it’s important to say that these areas exist to this day in their own cultural ecosystems, alive in a way that non-native people might find hard to understand. It goes without saying that they existed before Amherst was known even as a name – a name freighted with its own particular history. More about that, too, below.

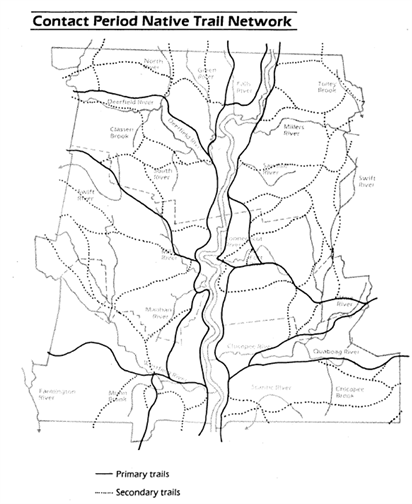

The first Native site is Bay Road, in South Amherst, that is an indigenous travel route, overlaid with Colonial era pathways – an area I wrote about this past summer and not so much a fixed point on a map (arguably, another overlay of white privilege) but a living, breathing network, “part of a Native American trail system used as a main thoroughfare linking western villages along the Connecticut River with hunting grounds to the east” closer – for example – to the Nipmuc heartlands of Central Massachusetts.

The second Native site is the lower hills of our Mill River corridor & Puffers Pond “with probable Early-Middle Woodland period components located …adjacent to the Mill River” (MHC Town Survey: Amherst, 1982). This designation by the Massachusetts Historical Commission means that the area was well traveled between 200 BCE to 500 CE. Before “…colonization [and much more intensive agricultural practices and industrialization,] the forested hills surrounding Puffer’s Pond were also hunting grounds and used as a place to gather plant resources for many Native American tribes for centuries.”

Characterized by water, Mill River, with its steep drop in elevation from the Shutesbury [hills], provided an opportunity for fishing in the pools carved into the rocks.” Annually, Pocumtuck peoples “burned the lowland portion of the Mill River watershed, reducing the forest underbrush, which provided better habitat for game and kept the rich floodplain soils cleared for farming.”

When reading this description, it is evident that Native settlement was much less extractive than more recent white settler land use. To this day, North Amherst is a fascinating part of our town (and deserves its own Month-by-Month article in the Indy). Thanks to a Community Preservation Act Committee grant, it is currently being researched for further forms of public interpretation and careful passive recreation.

The way the western European mind characterizes this era of local Native habitation historically is to say things like “…their impact on the land was relatively minor” as if it was insignificant or less important than the legacies of colonializing white settlers’ land management later on. Larry Spotted Crow Mann gave hints to why this might be so in his presentation last Sunday. He spoke about how his people have a language based on verbs while non-native languages are based on nouns. When you think about it, this has a profound impact on the way we walk the land – or tread more softly in our moccasins. I continue to try to ‘see’ and feel the landscape as an action, as something transformative but I doubt I will ever feel it ‘in my bones’.

But here is a way to perhaps think about languages that focus on verbs rather than nouns. Think or say the word “mother” – yes, a female human with a uterus and children but ‘mother’ can be a verb and can be valid for any gender or species, any sentient being dedicated to ‘mothering” and serving all of life’s sacred gifts on Turtle island. If you have read anything by author and member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, Robin Wall Kimmerer, author of Braiding Sweetgrass, you will recognize this way of talking about and touching the earth, its landscapes and ‘viewsheds’.

The present-day boundaries of the town of Amherst lie on top of the so-called purchase by John Pynchon of Springfield of Norwottuck tribal lands in 1658. The deed incorporates (think about that word) the land “from the mouth of Fort River and Mount Holyoke on the south, to the mouth of Mohawk brook and the southern part of Mount Toby, on the north, extending easterly nine miles into the woods.” Amherst is situated east of the Connecticut River, and south of Great Falls (Turners Falls) which is a good example of a rural community still dealing with the massacre of Peskeompscut-Wissantinnewag, an act of genocide that happened in May 1676 during King Philip’s War when Nipmuc peoples were killed in Gill and Greenfield, across from the Great Falls.

Amherst is named for Lord Jeffery Amherst who was a British army officer during the French-Indian Wars and the conquest of Canada around 1763. He believed … that the best way to control indigenous peoples was through a system of regulations and strict punishments when necessary. He is infamous for calling for their extermination by overseeing biological warfare in the Siege of Fort Pitt using blankets contaminated with smallpox. I first learned of this history at Amherst College’s Mead Art Museum. And it is due to this legacy that Amherst College is so fervently committed to race-conscious admissions, and stands “in solidarity with our peers fighting for the ability to find and recruit a truly diverse student body.”

Some people think our Indian ‘wars’ are still being waged in other guises. Perhaps instead we can make peace with the Earth, mother it, protect her waters and build on the evolution of land use by the public to demonstrate how landscape itself can be an effective and sustainable expression of culture. It is an integral part of historic preservation.

Some Events That Relate To This Article

Saturday, November 12, in Great Falls is the Full Beaver Moon Gathering from 11-2 at the Great Falls Discovery Center. Nolumbeka members will be unveiling the Peskeompskut mural commissioned by Town of Montague Artist Robert Peters who will speak and there will be music, etc.

Also,The Peskeompskut Audio Tour: Connect to historic, Indigenous, and personal narratives from your cell phone. Starts at Unity Park, Turner’s Falls. Free. Native and Industrial history on the Connecticut River narrated by David Brule.

Sunday,November 13: Ohketeau Cultural Center and Double Edge Theatre present the conversation, “The Living Presence of Our History, Part VII” live streaming on the global, commons-based, peer-produced HowlRound TV network at howlround.tv on Sunday 13 November 2022 at 10 a.m. PDT (San Francisco, UTC -7) / 1 p.m. EDT (New York, UTC -4). Rhonda Anderson, Co-Founder and Co-Director of Ohketeau, [with Larry Spotted Crow Mann] will curate a panel with Native American scholars, playwrights, and actors on the importance of seeing our narratives on stage and screen. Presented by The Ohketeau Cultural Center and Double Edge Theatre, this is the seventh in a series of panel conversations with Indigenous community members and allies regarding issues faced today by Native peoples. This panel will focus on Native playwrights.

Stone Soup Café, Greenfield, MA. Thanks Giving Day: “Since the 1970s, Indigenous people and their allies have gathered in Plymouth, MA on the Thanksgiving holiday to commemorate a National Day of Mourning. Many Native people do not celebrate the arrival of European settlers, and Thanksgiving Day is a reminder of the genocide of millions of Native people, the theft of Native lands, and the attempted erasure of Native cultures. The National Day of Mourning is a time to honor Indigenous ancestors and Native resilience. It is a day of remembrance and a protest against the racism and oppression that Indigenous people continue to experience worldwide. Many supporters will fast from sundown the day before, and break fast after the ceremony at noon in Plymouth.

At Stone Soup Café this year, we will be pausing all food preparations at 12 p.m. to watch a live stream of the National Day of Mourning in the All Souls [Church sanctuary.] We will break fast and serve the community meal shortly after 1 p.m. All are welcome to share a meal in the sanctuary after 1 p.m.

Amherst History Month-by Month is a monthly column on historic preservation, taking a look at Amherst’s historic buildings and neighborhoods and the stories behind them. It may also, from time to time, explore the challenges of historic preservation in a town such as ours that is so rich in historic resources. See previous columns here.

Hetty Startup lives and works in Amherst and is a member of the Amherst Historical Commission.

Thanks so much for Hetty Startup’s article on Native Lands and especially for the recognition that “Indian ‘wars’ are still being waged in other guises”. The genocide of indigenous people was based on the assumption that Native Americans are somehow ‘less than human’ and therefore had no rights. Today our treatment of anyone who looks, acts, or speaks different than “us” is based on a similar assumption. The celebration of November as the National Native American Heritage Month and the recognition of November 24, 2022 as a National Day of Mourning are small steps toward reparation and change.

Dear Hetty Startup,

You are a treasure.

Thank you for your contributions-always a highlight of any “Indy” issue making us all richer for the knowledge you share.

Hello Indy readers:

Some follow up comments about this article: first, thank you to John Gerber and Rita Burke for your comments. Secondly, is an apology. Just after it was published I realized that an article shared with a group of friends in Mothers Out Front Pioneer Valley had imprinted itself in my mind and I wanted to cite it as a source for the material on ‘mothering’ ideas for my own text here. I hadn’t realized that the wording was so close until it circulated back around in an email thread and there it was! So below is that citation, from the magazine Emergence.

The third comment is that The New Yorker just published a book review that takes a rather different approach from the one I have taken here. And so it goes. Where there is a story, there is another to tell.

1. https://emergencemagazine.org/essay/coming-into-being/

2.https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2022/11/14/do-we-have-the-history-of-native-americans-backward-indigenous-continent

Thanks so much, Hetty, for expanding our understanding!

Link here to an NEPM Connecting Point story: ” If you’ve been to the Native Hall at the Springfield Science Museum recently, you may have noticed some changes. They come from Aprell May, a Springfield resident, who is bridging the past and the present through her exhibit entitled “We’re Still Here.”

May’s exhibit honors and recognizes the ongoing history and culture of the Native communities in our region. Zydalis Bauer spoke with May to learn more about her personal connection to the exhibit and more. ” https://connectingpoint.nepm.org/were-still-here-explores-history-local-native-communities/?utm_source=watchlisten&utm_medium=enews&utm_campaign=nepm

And here is a wonderful resource by Marge Bruchac – she is giving an online talk for Historic Northampton on Thursday, March 9, 2023 at 7 pm and in the meantime her is this link: https://www.historicnorthampton.org/indigenous-native-history.html