Orchard Valley, Amherst: Reprising Social Housing and its Histories

A gathering of Orchard Valley residents, winter 2025. Photo: Facebook, courtesy of Darcy DuMont

Amherst History Month by Month

The history of housing in our region, especially the more affordable, socially progressive or visionary kind, is a narrative that is usually written from above, meaning from the perspective of the providers of it as a public service or product. What often gets left out from histories like this is the perspective of the consumer….and a record of what the homes were actually like to live in. With that in mind, I’ve been glad to start meeting with a group of women, all residents of Orchard Valley in Amherst, all interested in learning more deeply from each other about their community as well as their own lives in retirement. Following our first meeting last month, we decided to continue to meet over the summer. My sense is that our gatherings will serve purposes far beyond this article.

To set the scene, where exactly are we in Amherst? I missed including Orchard Valley in my earlier histories of housing for the Indy. Orchard Valley is in South Amherst and is accessed from West Street and West Pomeroy Lane/Moody Bridge Road. It is on a bus line and close to Hampshire College’s bucolic campus. Orchard Valley’s homes are adjacent to Butternut Farm, an affordable housing development managed by Wayfinders on Longmeadow Drive. Both housing developments are opposite the Plum Brook Recreation Area. The heart of this part of Amherst is the rotary on West Street where El Comalito, the West Street Coffee & Tea café, Sibie’s, Mission Cantina, and other little stores, restaurants, and services are located.

Orchard Valley features Markert’s Pond which began life in the 1930’s, is now encircled by Pondview Drive, and is fed from a tributary of the Fort River. Indeed, the Fort River, which runs to the Connecticut River, and its environs are probably one of the oldest features of this landscape, well known to local indigenous tribes, like the descendants of the Sokoki and the Pocumtuck, now identified as Nipmuc homelands. The native Nolwotogg/Nonotuck/Norwottuck name for the Fort River was Towunucksett.

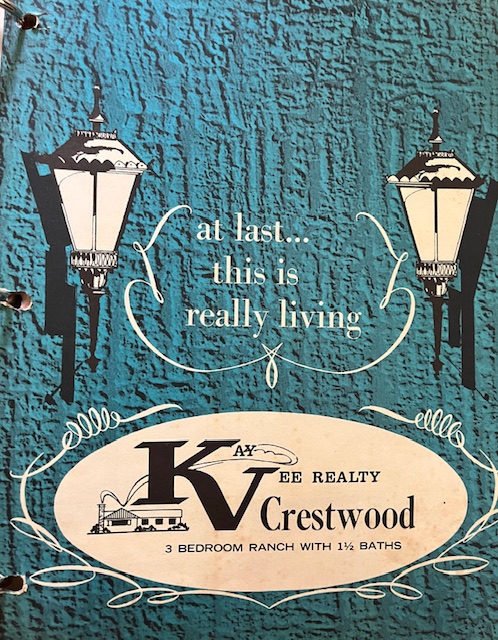

Kay-Vee Realty developed Orchard Valley in the early-to-mid 1960s and the company gave the subdivision its name. These sorts of nature-related names for new development can seem ironic as new construction replaces natural landscape and/or farmland. In this case, the development replaced apple orchards that had been established in the 1920s as well as a farm, Spring Farm, which was sold to Kay-Vee by the grandchildren of farmer Herman Markert. (Orchard Valley still feels semi-rural to me, even though it is less than three miles from Amherst Center and close to town services.) Its new homes appealed to struggling young professionals wanting to set up house.

Kay-Vee offered six styles of single-family homes, designed to appeal to people of relatively modest means. Some early residents were able to buy homes through the G.I. Bill, which allowed some veterans to get mortgages without a down payment. The houses were well-built and the neighborhood felt safe and suburban. Some women in the discussion group said they moved there because they were married to graduate students. There was also a sprinkling of high school teachers and other educators, and the development is still popular with educators.. Currently, the principal of Crocker Farm Elementary School lives here, and many families with ties to UMass. (UMass historically offered housing to faculty and married students with no more than two children, and those with larger families had to find their own housing.. Orchard Valley was developed in phases along feeder or “collector” roads when UMass was poised for one of its largest growth spurts. Phase II of the project was funded by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). At that time, the Hickory Ridge Golf Course and its clubhouse on West Pomeroy were also local attractions. The site of the former golf course is now owned by the Town of Amherst and the area near the intersection of West Street and West Pomeroy Lane has been designated “Pomeroy Village” by the town. .

Because Orchard Valley was built on a former apple orchard, there were initially public health concerns about the soil, which had been treated with arsenic. The soil also contained a lot of clay. After the developer removed the topsoil, residents worked diligently to establish gardens, and the town offered two free trees to each new homeowner. A few lots backed up to a stream while others were placed around a number of cul-de-sacs. One large residential lot quickly became the “go-to” site for beloved Fourth of July picnics and baseball games, all fondly remembered. Crocker Farm was the local elementary school, and most Orchard Valley children attended it, riding a school bus there and back. Every winter, a resident usually swept fallen leaves and other woody debris from Markert’s pond so that everyone could use it for skating.

Apart from the pond, another defining characteristic of Orchard Valley was the construction of cul-de-sacs. They are present of course in other Amherst subdivisions, but Orchard Valley was intentionally designed not on a grid plan but iwith a system of feeder roads (like Glendale Road, Longmeadow, Pondview, Deepwoods, and Farmington) and lollipop or loop shapes (Western Lane, Brookside Court, Lantern, Atwater, and Applewood, to name several) end in cul-de-sacs. Nationwide, perceptions of the cul-de-sac especially as a form of enhanced public—and especially children’s—safety have changed since Orchard Valley was completed. But at the time the positives related to the fact that children could play with little fear of fast-moving traffic. The feature was popular with developers of housing because it sold well and overall, required less new road construction. Traffic-calming techniques and strategies today draw from these now- historic examples.

The cul-de-sac of the American suburb has English/European roots. It made its U.S. debut in Radburn, New Jersey to help control through-traffic in the late 1920s. Radburn, according to one of its visionaries, would be “…a town in which children need never dodge motor-trucks on their way to school.” As a design idea it had first been developed by Garden Suburb proponents in the UK and Europe. It is a visual feature that appears alongside a revival of interest in community gardens (allotments, in the UK), onsite community centers and road design, generally-speaking, that was tied to the topography of the land. But cul-de-sacs and most little dead-end streets with homes on all sides date back to medieval cities in Germany and France that caught the attention of Camillo Sitte, a late 19th-century urban planner in Austria. Garden City architects and planners, especially Raymond Unwin (1863-1940) and his brother-in-law Barry Parker (1867–1947), as well as the visionary writer Ebenezer Howard, picked up on Sitte’s ideas and drawings thinking that cul-de-sacs and small dead-end streets would help reunite residents with the natural world. The phrase “cul-de-sac” is actually a French term for the bottom (or tail) of a bag, and you can see why it might have got this nickname.

This is the first of several articles taking a deeper dive into housing issues in Amherst. The Orchard Valley group will meet again in June or July. I am very appreciative of the members of the group and to Darcy Dumont for organizing the informal program of gatherings, research, and sharing of stories and photos.