Views on Views: Stone Walls

Historic stone wall near the MacNish Field Station. Photo: Smith College Botanic Garden instagram page.

This is the third article in a series of ten. Find the previous articles in the series here.

We owe so much to our prehistoric glacial past in Amherst in terms of how things look around here. I know this because colleagues more expert than I have schooled me and because I can see evidence of its legacy in the topography and its key geological features. What was once Lake Hitchcock is present in so many ways today in walks around Amherst and its neighboring towns (see also here).

I’ve been walking recently along a quiet country road; several very distinct ancient stone erratics (rocks transported and deposited by glaciers, often differing in composition from the local bedrock) from our prehistoric past and a tree farm are just as visible along with the few houses set back from the road. A brook feeds an historic mill that once existed downstream that used to manufacture tools. The waters of the brook run by the road, and the road has been accommodated to the path of the stream with small stone bridges, culverts and abutments.(When I see these little bridges over streams I often think of the Station Road bridge in South Amherst and the enormous costs to our town of replacing them; even a temporary bridge at this site is costing almost a million dollars. Friends who live in Ashfield are experiencing the disruption of a bridge being out for repair over Creamery Brook. It will likely be a one-way part of the road with a stop sign going forward. While we admire these small rivers and streams that are likely the tributaries of the Connecticut River, or Mill or Fort River (in Amherst) the roads over them are expensive to maintain.)

When I look into the clear, shallow water, it is evident that some of the stones are from the old stone walls close to the road that have tumbled down the hillsides to become part of the banks of the stream. The steep sides of the hills around are currently forested. I try to discern here the layers of habitation both distant, closer to the present time (sheep, other kinds of arable land) and newer forests.

In fact, when I try to read this particular forested landscape, I remember that I am inhabiting Tom Wessels’ world. Wessels, an ecologist, says being preoccupied by the contours of the land, even a stand of trees, or simply the condition and appearance of a single specimen is similar to other kinds of forensic activity. I tend to think historically – focusing on the material reality of my surroundings still acknowledging that they are alive to our indigenous neighbors in our midst. Views of the land are also the result of geological changes as well as more recent intense colonial agricultural production and extraction. As this is New England, I am also drawn to looking at the many stone walls in a land that is famously “two rocks for every dirt.” This is a folk saying but perhaps someone reading this knows its origin.

Back to my walk. Stone walls line the way up to a high meadow offering a welcome opening to a wider expanse of sky, a breathing space of sorts. On either mild or chillier November mornings, it is the stone walls from the era of European settlers in our midst that catch my attention, marking off views from a road or path, creating an edge to something else – they make experiences in nature that much more meaningful.

Stone walls in our area have been elevated by “Mending Wall,” the famous Robert Frost poem that offers both a material and a metaphysical appreciation of what the stones themselves might tell us about ourselves. At Frost’s farm in Derry, NH the historic site offers poems (on signs) along a trail behind the farmhouse which makes any visit more memorable.

Why does our region have such rocky soil? The short answer is end-moraine deposits, that is, ridges of unsorted glacial debris deposited at the farthest extent of a glacier’s advance. It is why we have roads with names like Rocky Hill Road. And stone walls over time have done a number of things: mark agricultural fields, define property boundaries or some specific sort of private realm; enliven the features of the landscape, especially its contours or views. They can also limit potentially precipitous effects of steep hills or incline, such as the steps to Mount Hope cemetery in Leverett in the photo below.

Leverett also has a town pound built in 1820 that is constructed of stone walls in a circular shape. Something like this civic amenity would have been weaker if made of wood. Stone stands the test of time.

In Ireland, dry stone walls are considered part of its Intangible Cultural Heritage (UNESCO), which adds to their significance. Similar initiatives exist in Croatia, Portugal, Greece ,and Spain.

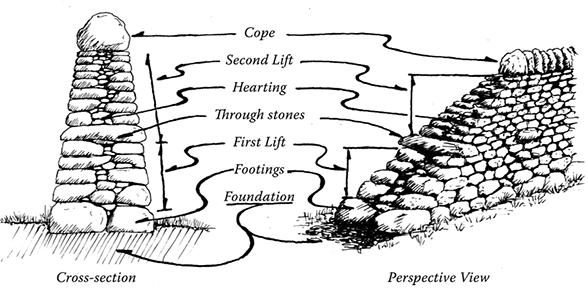

Where I grew up, country hedgerows in the west of England and privet hedges in cities like London were more likely to be the defining edges of a streetscape or landscape. But I do remember my father mending a dry stone wall once, letting my brother and I lift the smaller stones while my parents hefted the bigger ones, usually the ‘face’ and capstones of the wall.

And there are some good new stone walls in Amherst too. (see also here),

And we are also lucky to have some glacial types of stone that we can locally source from Ashfield with its distinctive pale green-ish gray tinge or Goshen.

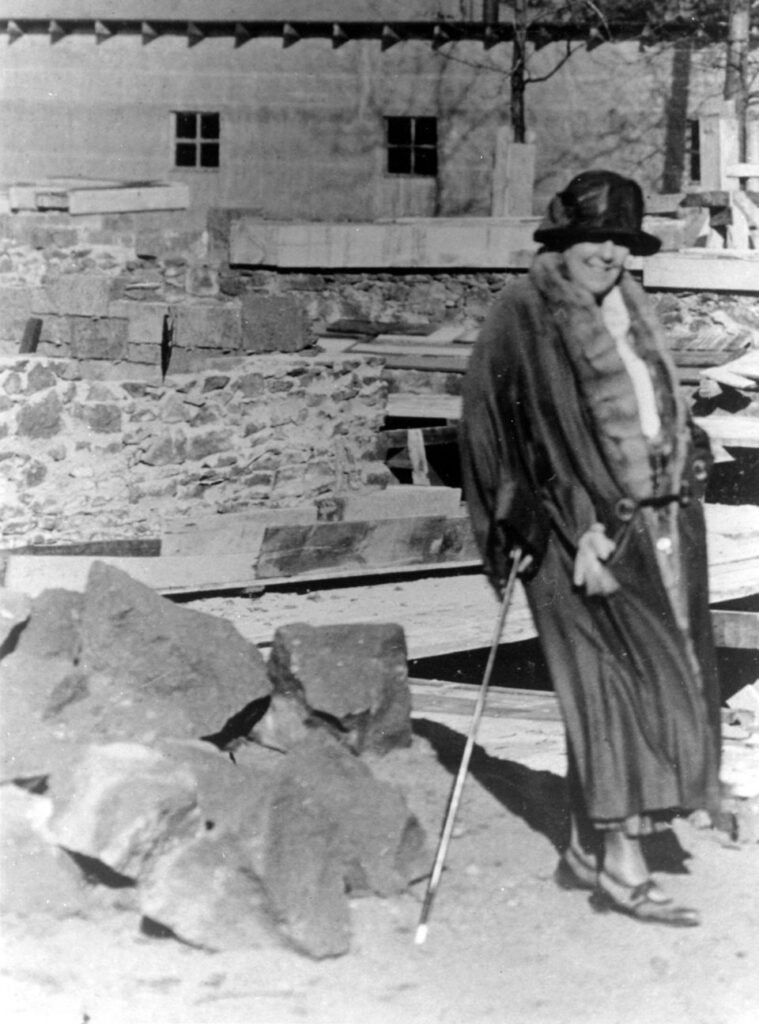

Further away I recall seeing the stone walls of landscape architect Beatrix Farrand’s garden at Hill-Stead, in Farmington, Connecticut,, a feature that the client, Theodate Pope Riddle, an architect herself, built into her “country place.” She also used traprock volcanic stones at her private school for boys at Avon Old Farms, Avon CT.

I hope readers have enjoyed this little wander around focusing on one aspect of the landscape. Parks in Amherst may come next or a focus on our amazing trail systems.

One correction to the funding needed for the Station Road bridge from https://www.masslive.com/news/2019/01/14m_to_build_temporary_than_pe.html