An Introduction To Police Abolition For Amherst Residents

Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

by Defund 413 Amherst

Last summer, in the wake of the murders of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbury, and Breonna Taylor by police, Defund 413 Amherst formed with the aim of redistributing funds from the Amherst Police Department to community services. In other words, our goal was to “defund” the police. Defunding the police is the first step toward abolition, because it allows us to invest in our communities rather than in punishment. The more our people are supported and the more they thrive, the less desire there is for policing.

We know that there’s a lot of confusion and misinformation about abolition and the movement to defund the police. So we wanted to share an introduction to these topics from our perspective as a resource for Amherst residents interested in learning more.

What Is Abolition?

Abolition is both a political theory and tangible goal that aims to reshape the way communities approach safety and security. Rather than focusing on punishment as a way to deter crime, abolitionists work to imagine and create communities where people’s needs are met without having to resort to law-breaking. Abolitionists ask questions like: What resources do our communities need to thrive? How can we resolve conflicts in a way that repairs our community?

Most of us grow up being told that crime and violence are caused by “bad” people who need to be removed from society for everyone to be safe. Abolitionists counter that argument to say that instances of interpersonal violence are often the result of oppressive circumstances created by violent systems, including the systems of white supremacy and racial capitalism. Additionally, abolitionists understand economic inequality, lack of access to safe and affordable housing, lack of access to affordable and nutritious food, mass incarceration (and prisons in general), racial and gender discrimination, and the forced removal of Indigenous people from their native land to be interconnected forms of violence which bring harm to everyone in our communities.

This systemic problem leads abolitionists to seek a systemic solution.

What Is The Purpose Of Policing?

In order to understand why defunding the police is a necessary step to achieving justice and equity in our communities, it’s necessary to first investigate what policing actually is and who (or what) it protects.

Although in the U.S. it is difficult for many of us to imagine a world without policing given the predominance of the institution in this country now, history shows that modern policing is actually a relatively new phenomenon. The first organized form of policing in North America was the slave patrol, which was created in the colonies of Carolina in 1704. A slave patrol was a group of four or five white men, armed with whips and sometimes guns, which hunted escaped slaves on horseback and created terror in slave communities in order to deter slaves from rebelling. Slave patrols were used in the South until the Civil War, at which point this form of organized terror was replaced by the Ku Klux Klan.

The history of policing in this country is rooted in anti-immigrant, anti-poverty, and anti-Black control. In the North, the first official police force was created in Boston in 1838 in response to complaints that poor Irish and German immigrants were causing chaos in the city. Following the establishment of the Boston Police Force, other cities created their own police departments in the ensuing decades, and by the 1880s almost every major city in the country had a police force.

As policing has developed and become permanent in the U.S. in the past few centuries, this institution has been used to target BIPOC, working class, immigrant, and queer communities, and to prevent marginalized groups from resisting by practicing intimidation and violence.

Last summer the world watched as Black Lives Matter protesters were tear gassed, corralled, beaten, and medical attention was withheld from them by police departments nationwide. In stark contrast, when white supremicists stormed the Capitol during the election certification, they were met with selfie sticks and “attaboys.”

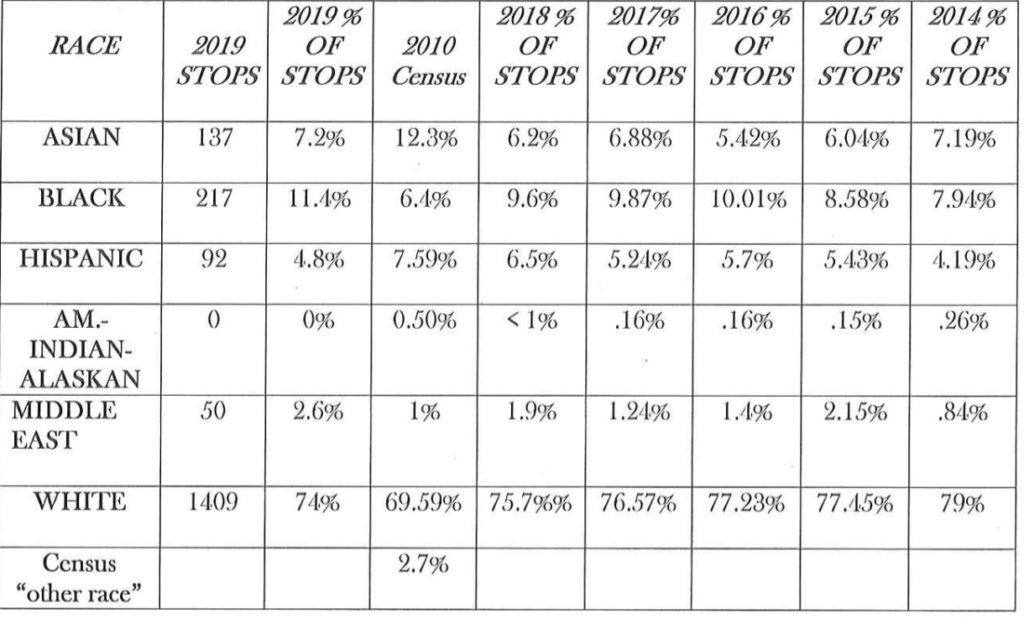

Disparate treatment of BIPOC people by police happens right here in Amherst too. You can see in the chart below that 11.4 percent of the traffic stops the APD made in 2019 involved a Black person even though Black people only make up about 6.4 percent of the town population. That means Black people were nearly twice as likely to be pulled over by police than would be indicated by town statistics.

Record of police stops by APD, submitted in response to a public records request filed by Defund 413 in July of 2020

One thing is clear. Police aren’t meant to protect and serve the community. Their true purpose is to uphold the institutions of white supremacy.

What Does It Mean To “Defund” The Police? Why Do People Want To?

Defunding the police is an abolitionist stance that seeks to reduce the power and influence of police departments in our communities by reducing their funding and instead spending public money on services that support community wellbeing, like public health programs, education, access to food, and affordable housing. This is in part because abolitionists believe that our communities deserve to have the resources to thrive and that police departments use a lot of funding that could be used to support the community.

The choice to fund community services with money taken from police departments isn’t arbitrary. Abolitionists believe that policing itself doesn’t reduce crime and is actively harmful to our communities. Policing negatively impacts people who are targeted by it, and racism means that policing disproportionately impacts community members of color.

Policing can negatively impact BIPOC people who are targeted by the criminal legal system as well as those who have never had a direct interaction with the police.

Getting arrested or going to prison is a profoundly traumatizing experience for people and the negative impact doesn’t end with the dropping of charges or the end of a prison sentence. Any interaction with the criminal legal system can make it difficult or impossible to get stable housing, employment, and income. These ramifications increase the need for communities to create support systems to help their residents survive and thrive.

The negative impact of policing can be deeply felt even by those who haven’t been arrested, as BIPOC Amherst residents who shared their experiences with consultants working for the Community Safety Working Group make clear:

- “As a Black person in America, I have to debate whether I should call the police because doing so may cause a situation to escalate and someone could end up dead because I called the police.”

- “I feel an anxiety when I see them even though I know I am not doing anything wrong.”

- “I don’t put myself in the position where I will have to have interaction with police, because, like I said, people who look like me, things can get from ugly to deadly.”

Defunding the police is a necessity to create a community where everyone feels comfortable asking for help and people are able to access the resources they need to prosper.

When we say “Defund the Police,” we mean fund our communities!

Why aren’t police reforms like community policing programs or increased training enough?

In the wake of violent murders of Black people by police, there are a few common responses:

- Inaction: “Thoughts and prayers”

- Reform: The police need more funding

- Abolition: We need to reduce the power and influence of policing

Abolitionists argue that a lot of the proposed reforms to policing won’t work, in part because we’ve tried them all before and they haven’t worked, but also because many of the reforms reinforce the power of existing police departments.

Abolitionist organization Critical Resistance argues that there are certain kinds of policy changes that can move our communities closer to abolition (“abolitionist reforms”) and other reforms that work to continue or expand the reach of police (“reformist reforms”). In this helpful chart, they evaluate a series of potential policy changes that communities can make to their police departments based on a series of questions to determine which ones are reformist and which are abolitionist.

The questions are as follows:

- Does this policy reduce funding to police?

- Does this policy challenge the notion that police increase safety?

- Does this policy reduce tools/tactics/technology police have at their disposal?

- Does this policy reduce the scale of policing?

Critical Resistance argues that if you have to answer “no” to any of these questions, a policy change is likely a reformist change that would only increase the power of policing in our communities.

A few of the policy changes that they identify as reformist reforms include: body cameras, community policing, more training, police oversight boards, and “jailing killer cops.” You’ll notice that these are often the kinds of policies that are put in place when the public demands a change to policing. However, these proposals fail most or all of the questions posed above. They all require giving more money to the police, do nothing to challenge the notion that police create safety, often create more tools for police to surveil communities, and broaden the reach of police departments.

In contrast, the policy changes that Critical Resistance identifies as reforms that bring us closer to abolition include: getting rid of paid administrative leave for cops under investigation, withholding pensions and refusing to rehire cops with use of force infractions, requiring cops to be personally liable in misconduct settlements, capping overtime, withdrawing from participation in militarization programs, prioritizing spending on community services, and reducing the size of the police force. All of these policy changes result in a smaller police budget and less power overall for police departments.

The lesson here is: police reforms can work, but only if they involve reducing the size and scope of police departments. And many of the popular reforms just don’t do that.

“But What About Rapists And Murderers?”

It is common for (white) people who are new to the idea of defunding the police and prison abolition to ask, “But what happens to the violent criminals if there are no more prisons? How will our communities be safe without police?”

Many of us who live in the U.S., particularly those of us who have been privileged enough to avoid being affected by police violence in our communities firsthand, have been taught by the dominant cultural narrative that policing and prisons are the “common sense” response to violence. This narrative has taught us that a world without policing would be inherently chaotic and unsafe. What this narrative fails to acknowledge is that police are not currently preventing violent crime, but responding after the violence has already occurred. The role of police is not proactive.

So what is currently done with people who have done harm? And is it working?

The current response to violence is largely reactive and relies heavily upon incarceration, a system that reproduces violence. However, research has shown harsh sentences do not effectively deter crime. Incarceration may actually increase the risk of future crime . Incarceration is a punishment — people are denied access to food, healthcare, meaningful connection, safety — that does not address the root cause of the harm that has been done, and often exacerbates the underlying issues. Incarceration does not provide an environment that supports taking accountability for harm caused. Incarceration serves to incapacitate, rather than rehabilitate.

Survivors of violent crime don’t universally want harsh prison sentences either. According to a 2016 survey of survivors of violence by the Alliance on Safety and Justice, 60 percent preferred shorter prison sentences and more spending on prevention and rehabilitation; 70 percent preferred that prosecutors focus on solving neighborhood problems through rehabilitation; and survivors were 3x more likely to prefer holding people accountable through options other than prison.

Additionally, because of the way our society stigmatizes sexual assault and the way our criminal legal system works, most sexual assault perpetrators don’t end up in prison. RAINN reports most sexual assaults are never reported and that 995 out of every 1,000 sexual assault perpetrators will walk free. We’ll leave this section with a helpful quote: “The criminal system is not designed to create survivor-centered responses to violence, to promote agency and healing in survivors, nor does it demand behavior change in the perpetrator. Like most white supremacist institutions, it is only designed to punish.”

How do I explain abolition to my children?

Abolition is something that children can understand and relate to in a very natural way. In fact, in some of our members’ discussions with their children, abolitionist principles seem to truly resonate with them. Of course policing and prisons do not make sense, they understand, punishment does nothing to take care of people who are hungry or need housing or health care.

Many of us have been taught that when we misbehave, punishment discourages us from repeating the behavior. We see this with kids a lot — they are given time out, grounded, and have their things and privileges taken away when they do things that are “wrong.” The thinking is that making them feel badly when they do “bad” things will make them less likely to do the “bad” thing again. In practice, though, we often see that this does not work, and children do not respond well to punishment. Why?

When a child has a temper tantrum, or yells at their parent, or hits another child, they are almost always expressing an unmet need. Maybe the child is hungry or tired; maybe they feel a lack of autonomy; maybe they feel unsafe; maybe they have been spoken to rudely, yelled at, and threatened, and this is how they have learned to interact. Regardless of the reason, punishing a child who is “misbehaving” does not teach them anything. Additionally, failing to find out why they acted the way they did means that we can do very little if anything to help them behave differently in the future. Furthermore, being punitive and unkind to someone in need teaches them to be as such, and that understanding and help are not available, should they need it.

Discipline, by definition, is not about control and punishment, but about teaching and guiding. Community is about taking care of each other and making others feel a sense of support, safety, and belonging with their neighbors. In this way, it is very easy to talk to children about abolishing the police; they can relate to it quite well.

There are many resources available to support families in talking to children about abolition. For some really great advice on language and specific suggestions for talking points, check out the Portland Childcare Collective’s piece on talking to kids about abolition.

What Could Abolition Look Like In Amherst?

In order to dismantle the system of white supremacy inherent in policing, the voices of those most impacted by policing must be at the forefront in reimagining community safety. The Community Safety Working Group (CSWG) formed to lead this effort in Amherst and make budget recommendations for the FY22 year.

For the last five years of town budgets, the Town of Amherst has dedicated only 7.8 percent of its budget to “Community Services.” For comparison purposes, “Public Safety” constituted 45.4 percent of the General Fund expenditures. This means that almost half of our town operating budget is used to fund policing, fire, and EMT services, but less than 10 percent is used to fund programming to proactively support our community (FY21 Proposed Municipal Budget, pg 13). This means less than 10 percent is used to fund things that would actually keep our communities safe, things like housing programs, food programs, health and wellness programs.

Almost half of our town’s operating budget is used to punish people for problems after they already exist. Abolitionists want to work to create a community that provides support to people and addresses these problems in a systemic way before they occur.

The CSWG has proposed a number of community initiatives that would shift the power away from police and build a more inclusive town. Their first recommendation is that Amherst create a “Community Responders for Equity, Safety, and Service” (aka CRESS) program as a civilian, unarmed alternative response to police in non-violent, non-criminal situations. In Amherst, 93.6 percent of calls to the police would fit into this category (FY21 Proposed Municipal Budget, pg 52). Operating separately from the Police Department will decrease the violence of the response in situations of mental health, substance use, trespassing, truancy, wellness checks, noise complaints, traffic stops, houselessness, and other non-violent situations. CRESS staffing would incorporate responders with expertise in clinical mental health, social work, de-escalation, and medicine, as well as dedicated dispatchers. The CRESS program would take a consciously anti-racist approach in providing services. Read more about CRESS here.

Another recommendation specifically regarding the Amherst Police Department is to cut the number of officers in half over the next five years.

View the slide show from 7 Generations Movement Collective, presented to the CSWG on 4/28/2021

Additionally, CSWG recommends creating an office of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion for the town with qualified BIPOC leadership and program funding. Initiatives under this office would include a youth empowerment center, transitional housing, rental assistance, and a multi-cultural center. Providing youth in town with a safe space for recreational and educational opportunities enhances positive development.

If you have been swayed by this article, please tell your town councilor via email or at the May 17 Public Budget Hearing to divert money from the Amherst Police Department budget to fully fund the CRESS program and the other community initiatives recommended by the Community Safety Working group. Defund the police to fund our Community.

Defund 413 Amherst

Connect with us on Instagram at @defund413amherst and on our Facebook Group

2 thoughts on “An Introduction To Police Abolition For Amherst Residents”